Birds typically molt once a year, though the frequency and timing of molting vary significantly among species, age, and environmental conditions. The process of feather replacement, known as molting, is essential for maintaining flight efficiency, insulation, and overall health. A natural longtail keyword variant such as 'how often do birds molt each year' helps clarify that while annual molting is common, some birds may undergo partial or multiple molts depending on their biology and habitat.

Understanding the Molting Process in Birds

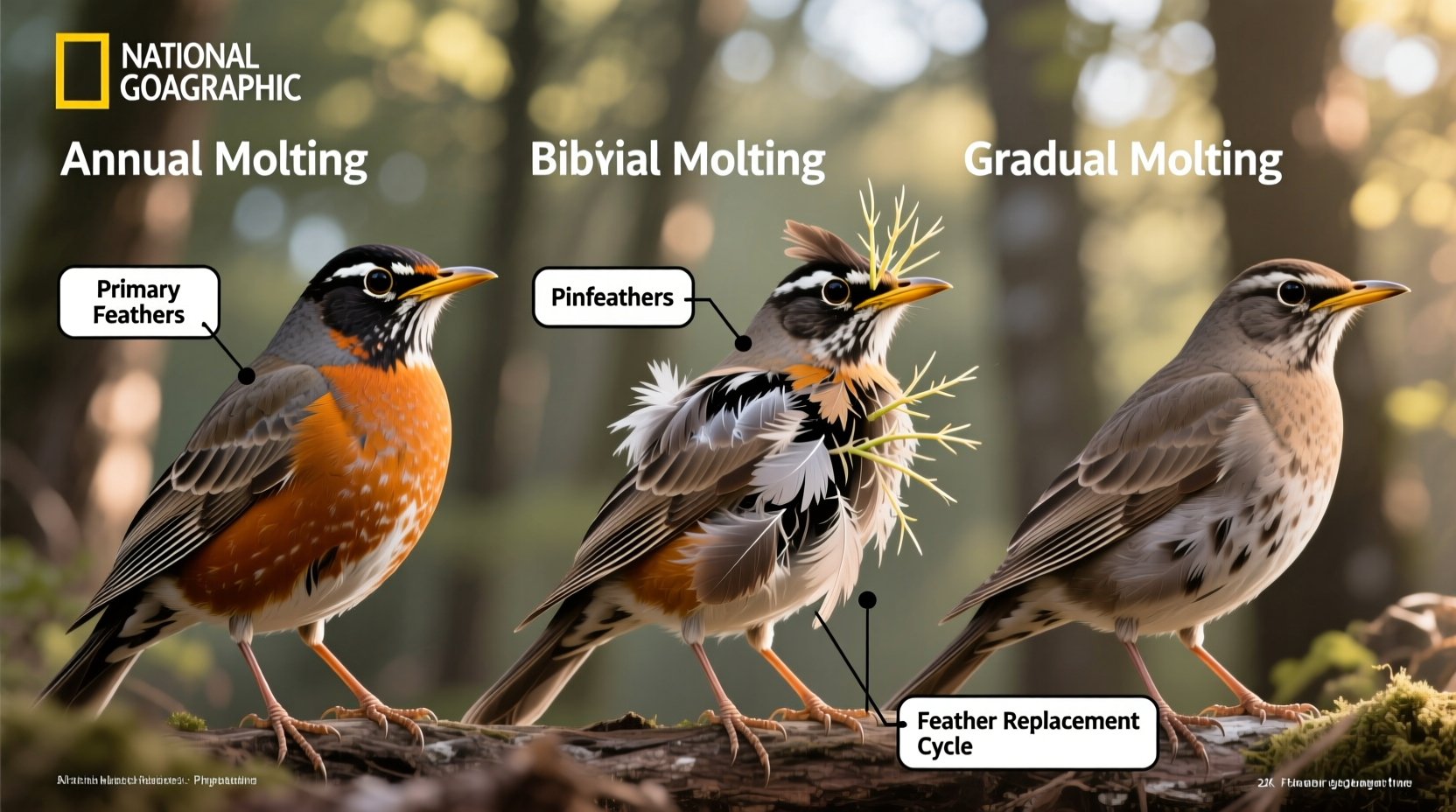

Molting refers to the periodic shedding and regeneration of feathers. Unlike mammals that continuously replace hair, birds undergo a more structured and energy-intensive cycle. Feathers are made of keratin and, once grown, are dead structures. Therefore, when worn or damaged, they must be replaced entirely through molting. This process ensures birds maintain optimal aerodynamics, waterproofing, and thermoregulation.

The frequency of molting depends largely on the bird’s life history. Most passerines (perching birds like sparrows and finches) experience a complete post-breeding molt each year, usually in late summer or early fall. This allows them to replace worn feathers after the demanding breeding season. Waterfowl, such as ducks and geese, often undergo a simultaneous wing molt, rendering them flightless for a short period—typically 3–4 weeks—while new flight feathers regrow.

Factors Influencing Molting Frequency

Several biological and ecological factors influence how often birds molt:

- Species-specific patterns: Some birds, like many raptors, molt gradually over several years, replacing only a few flight feathers annually. Others, such as certain seabirds, may molt every two years due to longer lifespans and slower reproductive cycles.

- Age: Juvenile birds often have a pre-basic molt shortly after fledging, followed by adult-like molting patterns. Immature birds may exhibit different molting schedules compared to adults.

- Climate and geography: Tropical birds may show less synchronized molting due to stable climates, whereas temperate-zone birds align molting with seasonal resource availability.

- Nutrition and health: Poor diet or disease can delay or disrupt molting. Adequate protein intake is crucial, as feathers are over 90% protein.

For example, the American Goldfinch molts twice a year—one full molt in winter and a partial one in spring—resulting in its bright yellow breeding plumage. This bimodal pattern is relatively rare but highlights the diversity in avian molting strategies.

Seasonal Timing and Environmental Cues

Molting is tightly linked to photoperiod (day length), hormonal changes, and food availability. In temperate regions, most birds begin molting after breeding ends, typically from July to September in the Northern Hemisphere. This timing avoids overlap with energetically costly activities like nesting and migration.

However, migratory species must carefully time their molt. Many shorebirds initiate pre-migratory molting on stopover sites where food is abundant. Arctic-nesting species, such as the Red Knot, undergo rapid molts to prepare for long-distance flights. Delayed molting due to poor feeding conditions can jeopardize survival during migration.

In contrast, resident tropical birds may not follow strict annual cycles. Some hummingbirds and parrots show irregular or continuous feather replacement, making it difficult to define a single 'molting season.' These variations underscore why understanding 'how often do birds molt' requires context beyond a simple annual answer.

Molting and Migration: A Delicate Balance

For migratory birds, molting and migration are two of the most energy-demanding processes. Because both require substantial metabolic resources, they are rarely performed simultaneously. Most species adopt one of three strategies:

- Pre-migratory molt: Complete feather replacement before departure (e.g., many warblers).

- Post-migratory molt: Molt occurs after reaching wintering grounds (common in some flycatchers).

- Staged molt: Begin molting at breeding sites, pause during migration, and resume on wintering areas (seen in some thrushes).

This strategic separation prevents physiological stress overload. Birdwatchers should note that observing molting activity can help identify migration status and population health.

How Long Does Molting Last?

The duration of molting varies widely. Small songbirds may take 6–8 weeks to complete a full molt, while larger birds like eagles or albatrosses can take over a year to fully replace all flight feathers. During this time, birds often reduce activity levels, avoid predators more cautiously, and may appear scruffy or patchy.

A useful rule of thumb: the larger the bird and the more complex its wing structure, the longer the molt. For instance, a Bald Eagle replaces its primary feathers sequentially over several years, ensuring it remains capable of flight throughout the process.

| Bird Type | Molting Frequency | Duration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Songbirds (e.g., Robin) | Once annually | 6–10 weeks | Post-breeding; full body molt |

| Ducks (e.g., Mallard) | Twice yearly | 3–4 weeks (wing molt) | Simultaneous wing feather loss; flightless phase |

| Raptors (e.g., Hawk) | Gradual, multi-year | Years | Asymmetrical molt; maintains flight |

| Parrots | Continuous or biannual | Ongoing | Feather dust common; needs high-protein diet |

| Seabirds (e.g., Albatross) | Every 1–2 years | Up to 12 months | Tied to breeding cycle |

Recognizing Molting in Wild and Captive Birds

Birdwatchers and pet owners can identify molting through behavioral and physical signs:

- Visible feather loss: Not baldness, but symmetrical feather drop, especially on wings and tail.

- New pin feathers: Waxy-looking shafts emerging from follicles, often with blood supply visible initially.

- Increased preening: Birds spend more time grooming new feathers as sheaths break open.

- Behavioral changes: Reduced singing, flying, or social interaction due to discomfort or energy conservation.

In captivity, providing extra nutrition—especially proteins, vitamins A, D, and B-complex—and minimizing stress supports healthy molting. Avoid handling birds roughly during this time, as pin feathers are sensitive.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Molting

Several myths persist about avian molting:

- Misconception 1: “Birds molt whenever they lose feathers.”

Reality: Occasional feather loss is normal wear-and-tear; true molting is a coordinated, systemic process. - Misconception 2: “Molting happens overnight.”

Reality: It’s a gradual process spanning weeks or months. Sudden feather loss may indicate illness or plucking. - Misconception 3: “All birds molt at the same time.”

Reality: Timing varies by species, location, and individual condition. Urban birds may molt later due to extended light exposure.

Understanding these distinctions helps prevent misdiagnosis in pet birds and improves observational accuracy in field studies.

Regional and Urban Variations in Molting Patterns

Geographic location influences molting schedules. In North America, most landbirds molt between July and October. In Australia, where seasons are reversed, molting peaks from January to April. Additionally, urban environments can alter natural rhythms. Artificial lighting and warmer microclimates may shift hormonal triggers, leading to earlier or prolonged molting periods.

Climate change is also affecting molting phenology. Studies show some European species now begin molting earlier due to warmer summers. Such shifts could create mismatches with food availability, impacting survival rates.

Supporting Birds During Molting: Tips for Observers and Caretakers

Whether you're a backyard birder or avian caretaker, supporting birds during molting enhances their well-being:

- Provide high-quality food: Offer protein-rich options like mealworms, eggs, or specialized bird feed. Hummingbird nectar alone won’t support feather growth.

- Maintain clean water sources: Bathing helps loosen feather sheaths and reduces parasites.

- Minimize disturbances: Avoid loud noises or sudden movements near molting birds.

- Monitor for problems: Asymmetrical feather loss, skin lesions, or excessive scratching may signal mites, infection, or nutritional deficiency.

For pet birds, consider supplementing with vet-approved avian vitamins during molt, but avoid over-supplementation, which can cause toxicity.

Scientific Research and Monitoring of Molting

Ornithologists study molting to understand population dynamics, aging techniques, and climate impacts. By examining feather wear and replacement sequences, researchers can estimate a bird’s age and breeding history. Standardized codes (like the Howell system) allow consistent documentation across species.

Citizen science projects, such as eBird and Project SNOWstorm, rely on public observations to track molting patterns across regions. Photographs showing molt limits—the boundary between old and new feathers—are particularly valuable for research.

Frequently Asked Questions About Bird Molting

- Do all birds molt?

Yes, all bird species undergo some form of molting, though the pattern and frequency differ. - Can molting affect flight?

In most birds, flight is maintained due to sequential feather loss. However, waterfowl and some game birds become temporarily flightless. - How can I tell if my pet bird is molting or sick?

Molting involves symmetrical feather loss and new pin feather growth. Illness often causes random bald patches, lethargy, or discharge. - Does molting hurt birds?

Pin feathers are sensitive and contain nerves and blood vessels, so birds may seem irritable, but the process is natural and not painful under normal conditions. - Can stress stop molting?

Yes, extreme stress, poor nutrition, or illness can delay or interrupt molting. Chronic stress may lead to abnormal feather development.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4