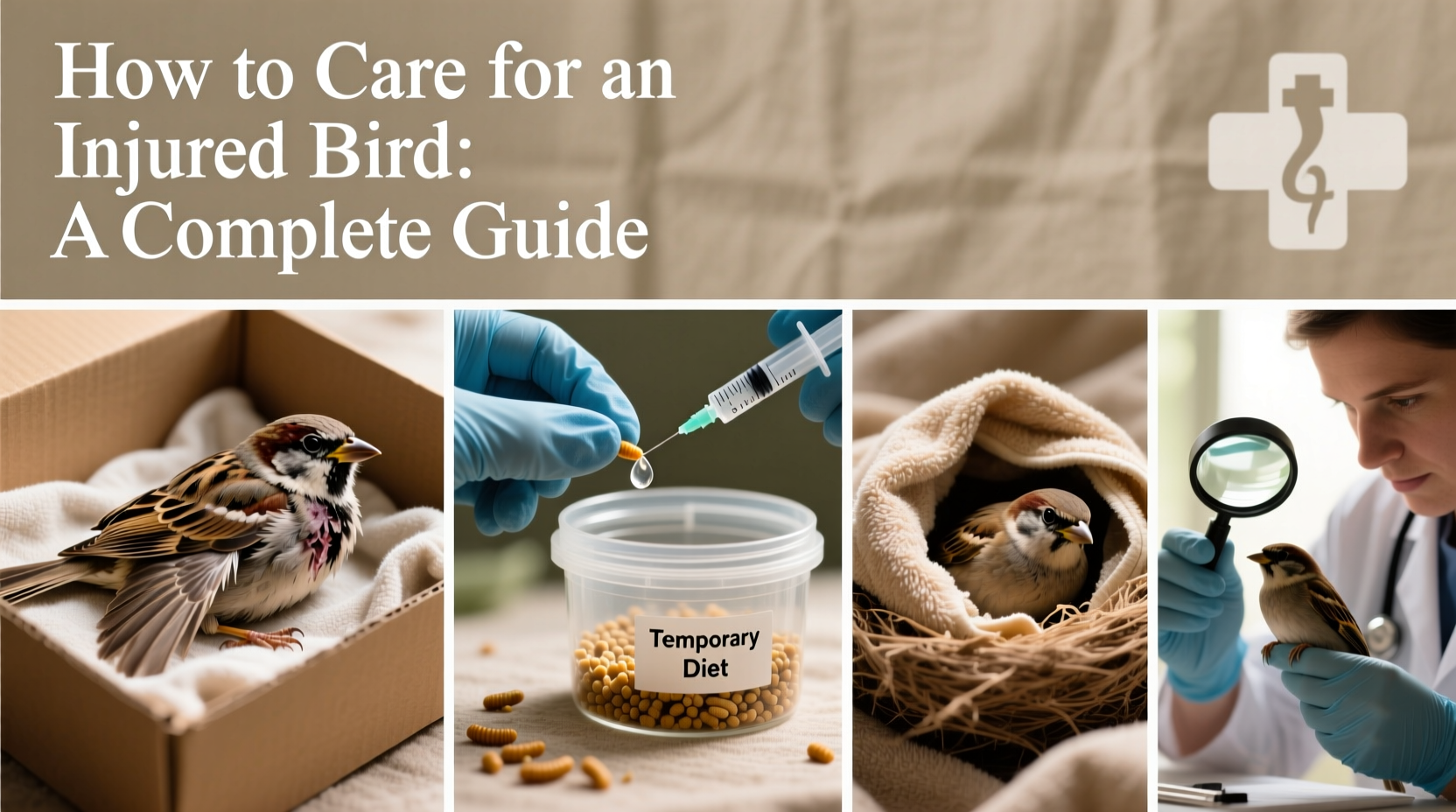

If you've discovered a hurt or grounded bird and are wondering how to care for an injured bird, the most important first step is to remain calm and avoid immediate handling unless absolutely necessary. Properly caring for an injured bird involves assessing its condition, minimizing stress, and quickly connecting with a licensed wildlife rehabilitator. While it may be tempting to bring the bird home or feed it, doing so without proper knowledge can cause more harm than good. Understanding the correct procedures—such as safe capture techniques, appropriate containment, and knowing when not to intervene—is essential in maximizing the bird’s chances of recovery and eventual release back into the wild.

Understanding Bird Injuries: Common Causes and Signs

Birds can suffer injuries from a variety of sources, including collisions with windows or vehicles, predation attempts by cats or other animals, exposure to toxins, entanglement in string or netting, and even natural causes like illness or malnutrition. Recognizing the signs of injury is crucial in determining whether intervention is needed.

Common indicators that a bird may be injured include:

- Visible wounds, bleeding, or broken bones (especially wings or legs)

- Inability to fly or stand properly

- Lethargy or unresponsiveness

- Fluffed-up feathers (a sign of distress or illness)

- Labored breathing or wheezing

- Drooping wings or inability to hold the head up

It's important to note that some young birds, particularly fledglings, may appear helpless but are actually under parental care. Before assuming a bird needs help, observe from a distance for at least 30 minutes to see if adult birds return to feed it.

When to Intervene—and When Not To

One of the most misunderstood aspects of how to care for an injured bird is knowing when human intervention is truly necessary. Many well-meaning individuals mistakenly 'rescue' healthy fledglings during nesting season, disrupting natural development.

Do intervene when:

- The bird has obvious trauma (e.g., hit by car, attacked by cat)

- It is bleeding, convulsing, or completely immobile

- You find a nestling (featherless or partially feathered) on the ground with no nearby nest

- The bird is in immediate danger (e.g., in traffic, near predators)

Do not intervene when:

- The bird is a fledgling with developed feathers, hopping around, and vocalizing (parents are likely nearby)

- There is no visible injury and the bird appears alert and active

- The bird is a waterfowl or raptor that appears healthy and is in a natural setting

In cases of uncertainty, contact a local wildlife rehabilitator for guidance before acting.

Safely Capturing and Containing an Injured Bird

If you determine that the bird requires assistance, the next step in how to properly care for an injured bird is safe capture and containment. Stress can be fatal to injured birds, so this process must be done gently and efficiently.

- Prepare a container: Use a cardboard box or pet carrier with air holes. Line the bottom with a soft, non-looping material like a cotton towel or paper towels. Avoid terry cloth, which can snag claws or toes.

- Approach slowly: Move quietly and avoid sudden motions. Cover the bird with a light sheet or towel to reduce visual stimulation and prevent panic.

- Secure the bird: Gently place your hands over the bird, supporting its body and wings. For larger birds, use gloves to protect yourself from beaks and talons.

- Place in container: Put the bird inside the prepared box, ensuring it cannot move around excessively. Close the lid securely but allow airflow.

- Keep in a quiet, warm place: Place the container in a dark, quiet room away from pets, children, and noise. Maintain a temperature between 85–90°F (29–32°C), using a heating pad on low underneath half the box if needed—but never let the bird sit directly on heat.

What NOT to Do When Caring for an Injured Bird

Misguided attempts to help often lead to further complications. Here are critical mistakes to avoid in how to care for an injured wild bird:

- Don't force-feed or give water: Improper feeding can cause aspiration pneumonia or digestive issues. Birds in shock may not eat or drink, and forcing fluids can be deadly.

- Don't bathe the bird: Cleaning or wetting an injured bird increases stress and risk of hypothermia.

- Don't keep the bird long-term: Only licensed rehabilitators can legally care for native wildlife long-term. Holding onto a bird delays professional treatment.

- Don't house with other animals: Even seemingly friendly pets can transmit diseases or cause stress through scent or sound.

- Don't release prematurely: Releasing a bird before it’s fully recovered reduces survival chances dramatically.

Finding Professional Help: Contacting Wildlife Rehabilitators

The cornerstone of effective care for injured birds is prompt transfer to a licensed wildlife rehabilitator. These professionals have the training, permits, and medical resources to treat injuries, manage nutrition, and prepare birds for release.

To locate help:

- Search online for “wildlife rehabilitator near me” or “bird rescue [your city/state]”

- Contact local animal control, veterinary clinics, or nature centers—they often have referral lists

- Use national databases such as the National Wildlife Rehabilitators Association (NWRA) or state-specific wildlife agencies

- Call your state’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR) or Fish and Wildlife office

Note that services may vary by region. Rural areas may have limited access, while urban centers often have multiple options. Always call ahead—some facilities do not accept walk-ins or require appointments.

Biological Considerations in Bird First Aid

Understanding basic avian biology enhances your ability to provide appropriate temporary care. Unlike mammals, birds have high metabolic rates, rapid heartbeats, and sensitive respiratory systems. This makes them prone to shock and dehydration.

Key biological factors to consider:

- Thermoregulation: Small birds lose body heat quickly. Hypothermia is a major risk, especially in fledglings or those exposed to rain.

- Respiratory sensitivity: Birds breathe rapidly and are highly sensitive to fumes, smoke, and aerosols. Keep them away from kitchens, cleaning products, and scented candles.

- Stress response: Visual stimuli, noise, and handling can trigger acute stress, leading to cardiac events. Darkness and silence are protective.

- Nutritional needs: Different species require specific diets (insects, seeds, nectar, etc.). Offering incorrect food can be harmful.

| Injury Type | Signs | Immediate Action |

|---|---|---|

| Window collision | Dazed, unresponsive, fluttering weakly | Contain and monitor for 1–2 hours; if no recovery, contact rehabber |

| Cat attack | Puncture wounds, lethargy, infection risk | Seek urgent care—even small bites can be fatal due to bacteria |

| Wing/leg fracture | Dragging limb, drooping wing, inability to perch | Minimize movement; transport immediately |

| Oil or chemical exposure | Matting, loss of buoyancy (waterbirds), shivering | Do not wash; wrap gently and transport to specialized center |

| Orphaned nestling | Featherless, eyes closed, on ground | Attempt nest re-nesting; if impossible, contact rehabber |

Cultural and Symbolic Perspectives on Injured Birds

Beyond biology, birds hold deep symbolic meaning across cultures. An injured bird may evoke feelings of vulnerability, loss, or spiritual messages. In many Native American traditions, birds are seen as messengers between worlds; finding one injured might be interpreted as a call to reflect on personal imbalance or emotional distress.

In European folklore, aiding a wounded bird was believed to bring good fortune, while harming one could invite misfortune. These narratives underscore humanity’s long-standing emotional connection to birds and reinforce ethical responsibility toward their welfare.

While these beliefs are meaningful, they should not replace evidence-based care. Compassion must be paired with scientific understanding to ensure the best outcome for the animal.

Legal and Ethical Responsibilities

In the United States, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) protects over 1,000 species of native birds, making it illegal to possess, transport, or care for them without federal and state permits. Violations can result in fines up to $15,000 per bird.

This law exists to prevent well-intentioned but harmful interventions and to ensure birds receive expert care. Temporary holding (24–48 hours) for the purpose of transferring to a licensed facility is generally tolerated, but long-term custody is not permitted.

Always verify the credentials of any individual or organization claiming to care for wild birds. Legitimate rehabilitators will have state and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service permits.

Tips for Preventing Bird Injuries

While learning how to care for an injured bird is valuable, prevention is even better. You can significantly reduce risks in your environment:

- Make windows safer: Apply UV-reflective decals, use screens, or install external netting to prevent collisions.

- Keep cats indoors: Outdoor cats kill hundreds of millions of birds annually in the U.S. alone.

- Avoid pesticides: These reduce insect populations (food sources) and can poison birds directly.

- Provide safe water sources: Use shallow birdbaths with rough surfaces to prevent drowning.

- Remove or secure hazards: Discard fishing line, six-pack rings, and plastic debris that can entangle birds.

FAQs About Caring for Injured Birds

- How long can I keep an injured bird at home?

- You should only keep an injured bird temporarily—ideally less than 24 hours—until you can transfer it to a licensed wildlife rehabilitator. Prolonged possession is illegal and harmful.

- What should I feed an injured bird?

- Do not feed or give water unless instructed by a wildlife professional. Incorrect food can cause serious health issues.

- Can I take an injured bird to a regular veterinarian?

- Some vets will provide emergency stabilization, but most lack the expertise or permits for long-term avian care. They can help direct you to a qualified rehabilitator.

- Is it safe to touch a wild bird?

- Yes, with precautions. Wear gloves if possible, and always wash hands thoroughly afterward. The risk of disease transmission to humans is low but not zero.

- What if I can’t find a wildlife rehabilitator?

- Contact your state wildlife agency or local animal control for referrals. In remote areas, transport may be required to the nearest facility.

Ultimately, the most compassionate and effective way to care for an injured bird is to act swiftly, minimize stress, and connect the animal with trained professionals. By combining empathy with knowledge, you can make a real difference in the life of a vulnerable creature while respecting ecological and legal responsibilities.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4