If you're asking how to catch bird flu, the answer is clear: humans do not intentionally 'catch' avian influenza—it is a serious zoonotic disease primarily transmitted through close contact with infected birds or contaminated environments. Understanding how to catch bird flu in the context of prevention and risk awareness—such as exposure to sick poultry, visiting live bird markets, or inadequate protective measures—is essential for public health and safety. This article explores the transmission, risks, symptoms, and preventive strategies related to avian influenza, blending biological facts with cultural perspectives on birds and disease.

What Is Bird Flu and How Does It Spread?

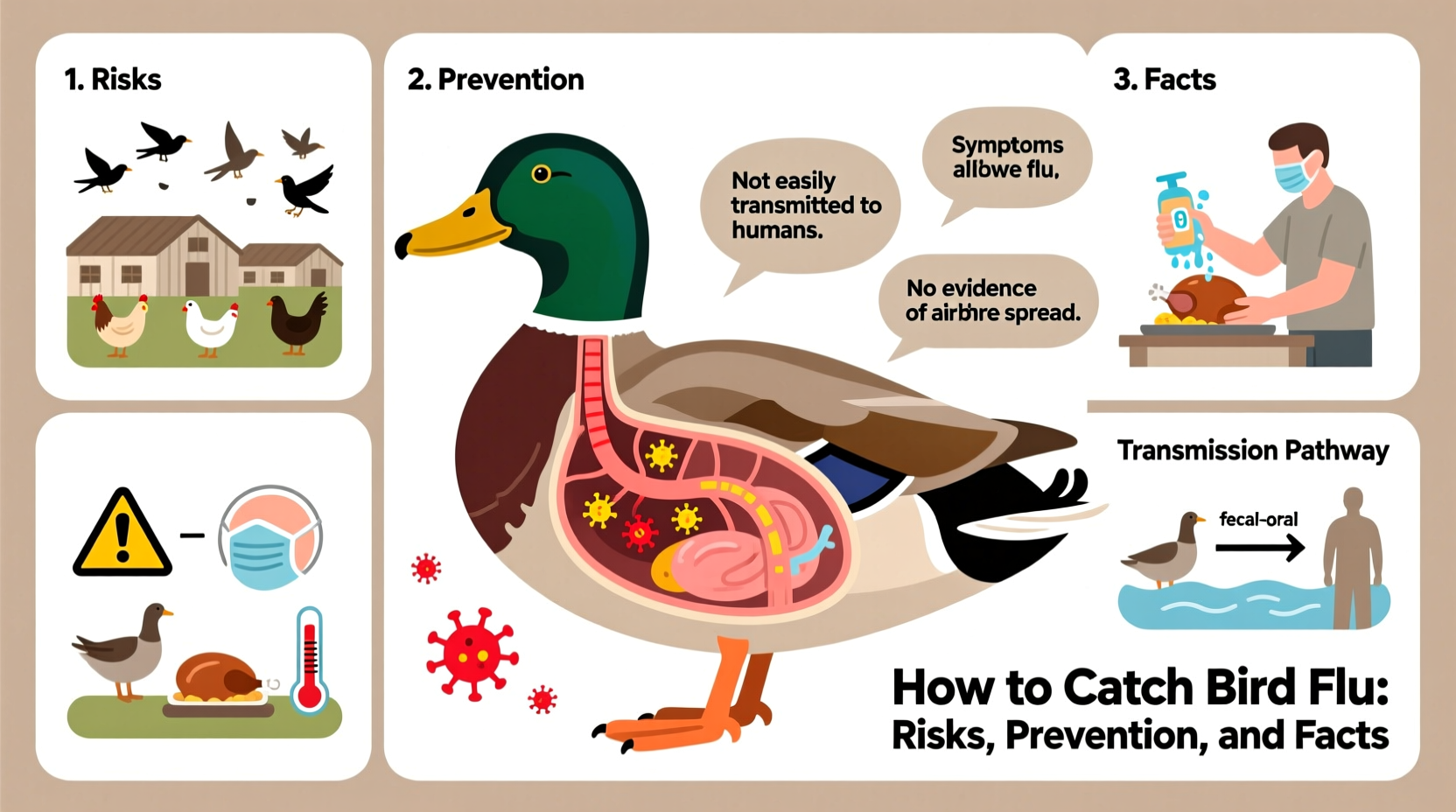

Bird flu, or avian influenza, refers to a group of influenza viruses that primarily infect birds. While these viruses naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds like ducks and geese, they can spread to domestic poultry such as chickens, turkeys, and quails. The most well-known strains include H5N1, H7N9, and H5N8, some of which have caused outbreaks with significant mortality in both bird populations and, rarely, in humans.

The phrase how to catch bird flu might sound alarming, but it's important to clarify: no one should seek to contract this illness. Instead, understanding how people may unintentionally catch bird flu helps prevent infection. Transmission to humans typically occurs through direct contact with respiratory secretions, feces, or surfaces contaminated by infected birds. For example, handling dead or sick birds, working in live poultry markets, or being exposed to contaminated cages or water sources increases the risk.

It’s worth noting that bird flu does not usually spread efficiently from person to person, which limits large-scale human outbreaks. However, health authorities remain vigilant because if the virus mutates to become easily transmissible between humans, it could lead to a pandemic.

Biological Basis of Avian Influenza

Avian influenza viruses belong to the Orthomyxoviridae family and are classified based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 16 H subtypes and 9 N subtypes known to circulate in birds. The H5 and H7 types are of particular concern because they can evolve from low pathogenic forms (causing mild symptoms in birds) to highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), which can result in rapid death in poultry flocks.

Wild migratory birds, especially waterfowl, often carry the virus without showing symptoms, making them silent carriers across continents. During migration seasons, these birds can introduce the virus to new regions, infecting domestic flocks either directly or via shared water sources. This ecological dynamic underscores why global surveillance systems monitor bird migration patterns and test samples from both wild and farmed birds.

In domestic settings, overcrowding, poor biosecurity, and lack of veterinary oversight increase the likelihood of an outbreak. Once introduced into a farm, the virus can spread rapidly due to close animal proximity. Culling infected and exposed birds remains a primary control measure to contain outbreaks.

Human Risk Factors: Who Is Most at Risk?

While anyone can potentially be exposed to bird flu, certain groups face higher risks. These include:

- Poultry farmers and farm workers

- Veterinarians and animal health inspectors

- Workers in live bird markets

- People involved in culling or disposing of infected birds

- Travelers visiting areas experiencing active outbreaks

These individuals may encounter the virus through inhalation of aerosolized particles, touching contaminated surfaces, or improper handling of infected birds without personal protective equipment (PPE). Family members of infected individuals have also been affected in rare cases, though sustained human-to-human transmission has not been documented.

Recent outbreaks, such as those involving H5N1 in 2024, have led to increased monitoring in countries across Asia, Africa, and parts of Europe and North America. Public health agencies recommend that travelers avoid bird markets and farms during visits to affected regions.

Symptoms of Bird Flu in Humans

Humans infected with avian influenza may experience symptoms ranging from mild to severe. Early signs resemble seasonal flu and include:

- Fever

- Cough

- Sore throat

- Muscle aches

- Headache

However, the illness can progress rapidly to more serious conditions such as pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and multi-organ failure. The case fatality rate for H5N1 in humans has historically been high—over 50% in some reports—though the total number of confirmed cases remains relatively low.

Because symptoms overlap with other respiratory illnesses, diagnosis requires laboratory testing, typically using nasal or throat swabs analyzed via RT-PCR. Prompt medical attention and antiviral treatment (e.g., oseltamivir) improve outcomes, especially when administered early.

Prevention: How to Avoid Catching Bird Flu

Understanding how to catch bird flu is ultimately about avoiding it. Preventive measures focus on reducing exposure and strengthening biosecurity. Key recommendations include:

- Avoid contact with sick or dead birds: Do not handle or consume poultry that appears ill or has died unexpectedly.

- Practice good hygiene: Wash hands thoroughly with soap and water after any potential exposure to birds or their environments.

- Cook poultry properly: Avian influenza viruses are destroyed by heat. Ensure all poultry meat reaches an internal temperature of 165°F (74°C), and eggs are fully cooked.

- Use protective gear: Individuals working with birds should wear gloves, masks, goggles, and disposable clothing.

- Support biosecurity in farming: Farms should restrict access, disinfect equipment, and separate new birds from existing flocks.

Vaccination of poultry is used in some countries to reduce viral spread, although it doesn't always prevent infection—only disease severity. Human vaccines for specific strains like H5N1 exist but are not widely available; they are typically stockpiled for emergency use during outbreaks.

Cultural and Symbolic Perspectives on Birds and Disease

Birds have long held symbolic significance across cultures—representing freedom, spirit, and omens. However, in times of disease outbreaks, perceptions shift. Historically, plagues and pandemics have been associated with animals perceived as carriers, sometimes leading to fear-driven actions like mass culling or stigmatization.

In parts of Southeast Asia, where backyard poultry farming is common, birds are deeply integrated into daily life and economy. Outbreaks of bird flu can devastate livelihoods and disrupt food security, creating tension between tradition and public health mandates. Educational campaigns that respect cultural practices while promoting safe handling are crucial.

Conversely, in Western societies, wild birds are often romanticized. Yet, during avian flu outbreaks, even feeding ducks in parks can pose risks if local waterfowl are infected. Public messaging must balance ecological appreciation with health awareness.

Global Surveillance and Response Efforts

Organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) collaborate to track avian influenza globally. They maintain databases of outbreaks, support lab capacity building, and issue guidelines for containment.

National governments implement surveillance programs, including routine testing of commercial and wild bird populations. When an outbreak occurs, authorities may impose movement restrictions, quarantine zones, and temporary market closures. Rapid reporting and transparency are vital to prevent international spread.

In 2024, several countries reported unprecedented levels of H5N1 in wild birds and poultry, prompting renewed calls for coordinated action. Climate change, habitat loss, and intensified agriculture may be contributing factors influencing transmission dynamics.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Despite scientific advances, myths persist. Here are some clarifications:

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| You can get bird flu from eating properly cooked chicken. | No—cooking destroys the virus. Safe food practices eliminate this risk. |

| Bird flu spreads easily between people. | No—human-to-human transmission is rare and not sustained. |

| All bird species are equally likely to carry the virus. | No—waterfowl are primary reservoirs; songbirds and raptors are less commonly involved. |

| Pets like parrots or canaries easily transmit bird flu to humans. | Extremely unlikely—no significant cases linked to household pet birds. |

What Should You Do If You Suspect Bird Flu Exposure?

If you’ve had close contact with sick or dead birds—especially in an area with known outbreaks—and develop flu-like symptoms within 10 days, seek medical care immediately. Inform your healthcare provider about your exposure history so they can initiate appropriate testing and infection control measures.

Do not attempt to treat yourself or wait for symptoms to worsen. Early antiviral therapy can reduce complications. Additionally, public health officials may need to trace contacts and monitor for further spread.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can I get bird flu from watching birds in my backyard?

No, casual observation poses no risk. Avoid touching birds or cleaning feeders without gloves if local outbreaks are reported. - Is there a human vaccine for bird flu?

Limited stockpiles exist for H5N1 and H7N9, but they are not part of routine immunization programs. - Are migratory birds responsible for spreading bird flu worldwide?

Yes, wild waterfowl play a key role in global dissemination, particularly along flyways. - Should I stop feeding wild birds?

In areas with active outbreaks, authorities may advise pausing bird feeding to reduce congregation and potential transmission. - How is bird flu different from seasonal flu?

Seasonal flu spreads easily among people and is caused by human-adapted strains; bird flu originates in birds and rarely infects humans.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4