If you're asking how to know if your chickens have bird flu, the answer lies in recognizing sudden behavioral changes, respiratory distress, decreased egg production, and high mortality rates within your flock. Avian influenza, commonly known as bird flu, can spread rapidly among poultry, and early detection is crucial for containment. Key warning signs include swelling around the eyes and head, purple discoloration of wattles and combs, nasal discharge, coughing, sneezing, and a noticeable drop in appetite or water intake. If your birds exhibit these symptoms—especially during peak bird flu seasons or after contact with wild birds—it's essential to isolate them immediately and contact a veterinarian or local agricultural authority.

Understanding Bird Flu: A Threat to Backyard and Commercial Flocks

Bird flu, or avian influenza, is caused by Type A influenza viruses that naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds like ducks and shorebirds. These species often carry the virus without showing symptoms, making them silent carriers. However, when the virus jumps to domestic poultry such as chickens, turkeys, and quails, it can cause severe illness and rapid death. There are two main forms: low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI), which may cause mild symptoms, and highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), which spreads quickly and has a mortality rate approaching 90–100% in unvaccinated flocks.

In recent years, outbreaks of HPAI—particularly strains like H5N1 and H5N8—have surged globally, affecting both commercial farms and backyard coops. According to the USDA and World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), thousands of poultry have been culled during major outbreaks to prevent further spread. The risk increases during migration seasons when wild birds come into proximity with domestic flocks, especially near wetlands or shared water sources.

Early Warning Signs: How to Spot Bird Flu in Your Chickens

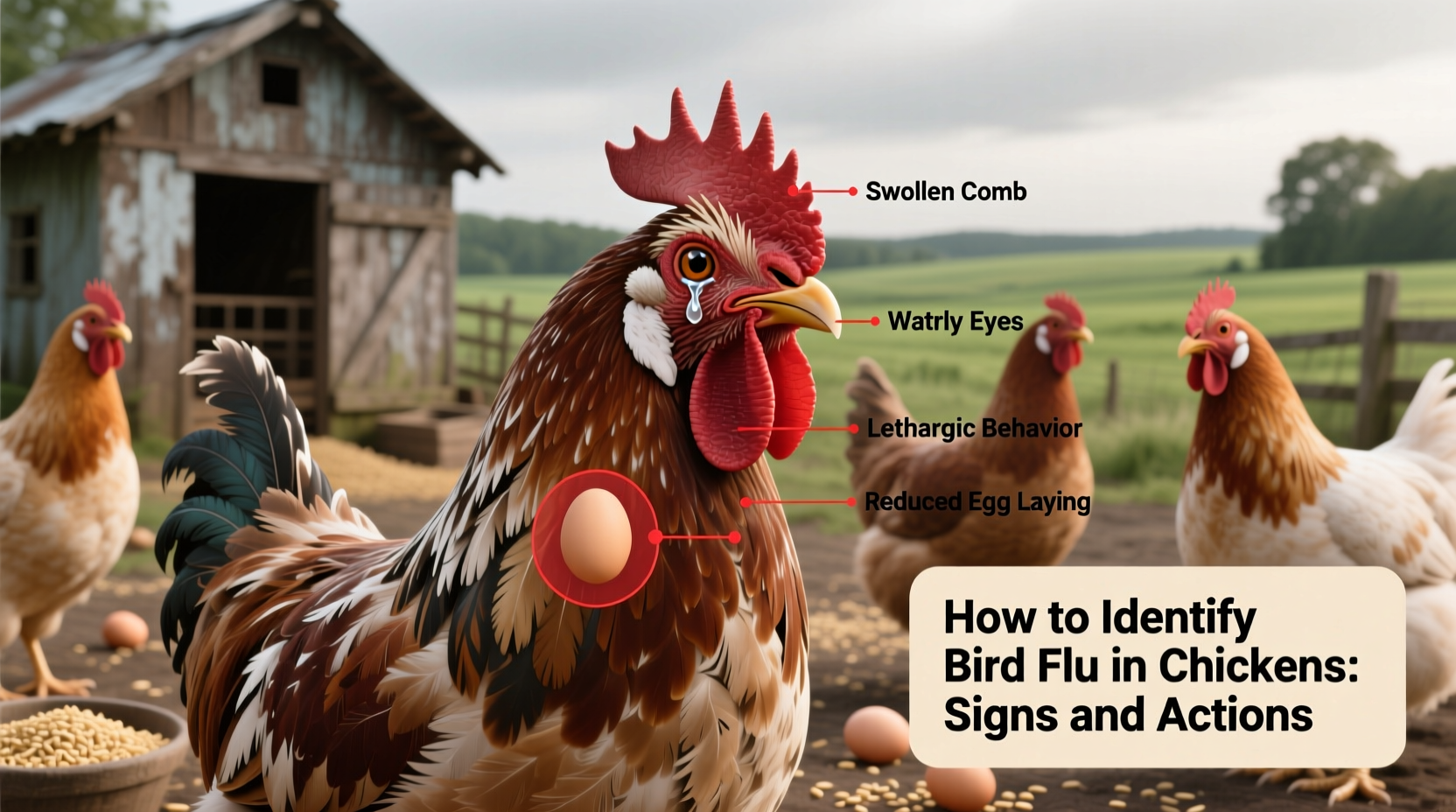

Recognizing the initial symptoms of bird flu is vital for protecting your entire flock. While some signs overlap with other poultry diseases, certain combinations strongly suggest avian influenza:

- Sudden death without prior illness: One of the most alarming indicators, particularly with HPAI, is finding multiple dead birds overnight with no obvious cause.

- Respiratory issues: Labored breathing, gasping, coughing, sneezing, and nasal discharge are common.

- Swelling and discoloration: Look for swollen heads, blue or purple combs and wattles (cyanosis), and edema around the eyes.

- Drop in egg production: A sharp decline—or complete cessation—of laying eggs can be an early clue.

- Neurological symptoms: Incoordination, tremors, twisted necks (torticollis), or paralysis may occur.

- Lethargy and loss of appetite: Infected birds often appear depressed, sit hunched, and avoid movement.

- Diarrhea: Watery green or yellow droppings may be present.

It's important to note that LPAI might only cause mild respiratory signs or reduced productivity, making it harder to detect without testing. But even low-pathogenic strains can mutate into more dangerous forms under farm conditions.

Differentiating Bird Flu from Other Poultry Diseases

Several illnesses mimic bird flu symptoms, so accurate diagnosis requires professional evaluation. Common look-alikes include:

| Disease | Similar Symptoms | Key Differences |

|---|---|---|

| Newcastle Disease | Coughing, sneezing, drop in eggs, neurological signs | Also causes diarrhea; vaccine-preventable; different virus family |

| Fowl Cholera | Sudden death, swollen face, respiratory distress | Caused by bacteria (Pasteurella multocida); treatable with antibiotics |

| Infectious Bronchitis | Respiratory issues, reduced egg quality | Affects eggshell formation; primarily viral but less fatal than HPAI |

| Avian Metapneumovirus | Swollen sinuses, nasal discharge | Less severe mortality; often linked to 'swollen head syndrome' |

Because visual inspection alone cannot confirm bird flu, laboratory testing is required. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests on swabs from the cloaca and trachea are the gold standard for identifying the virus strain.

Transmission Pathways: How Does Bird Flu Spread?

To understand how to prevent bird flu, you must first grasp how it spreads. The virus is primarily transmitted through:

- Direct contact with infected birds, including wild waterfowl.

- Contaminated feces and secretions, which can linger on surfaces, soil, feed, or water.

- Fomites—objects like boots, tools, cages, or vehicles that carry the virus from one location to another.

- Airborne particles in enclosed spaces, especially in high-density housing.

- Migratory birds, which introduce the virus seasonally, particularly in spring and fall.

The virus can survive for days in cool, moist environments and up to 30 days in frozen manure. This makes biosecurity measures critical year-round, not just during outbreak alerts.

What to Do If You Suspect Bird Flu in Your Flock

Immediate action can limit losses and prevent regional spread. Follow these steps if you suspect avian influenza:

- Isolate sick birds immediately. Prevent contact with healthy ones and restrict human access to the coop.

- Do not move any birds, eggs, equipment, or manure off your property until cleared by authorities.

- Contact your veterinarian or state animal health department right away. In the U.S., report to the USDA at 1-866-536-7593.

- Collect samples properly: Use sterile swabs from live symptomatic birds (tracheal and cloacal) or submit whole dead birds in sealed containers on ice.

- Enhance biosecurity: Disinfect footwear, tools, and clothing. Use footbaths with approved disinfectants like Virkon-S or bleach solutions.

- Monitor all birds daily for new symptoms and keep detailed records of deaths and behavior changes.

Remember: It is illegal in many countries to transport or sell birds suspected of having avian influenza. Euthanasia and disposal protocols will be directed by officials if infection is confirmed.

Prevention Strategies for Backyard Chicken Keepers

While there is no widely available vaccine for backyard flocks in the U.S., strong biosecurity practices significantly reduce risk:

- Limit exposure to wild birds: Cover outdoor runs, remove bird feeders nearby, and avoid letting chickens roam near ponds or wetlands.

- Practice strict hygiene: Wash hands before and after handling birds. Dedicate specific shoes and clothes for coop use.

- Quarantine new birds: Isolate newcomers for at least 30 days and monitor for illness.

- Secure feed storage: Keep feed in sealed containers to prevent contamination by rodents or wild birds.

- Control visitor access: Restrict non-household members from entering poultry areas.

- Stay informed: Subscribe to alerts from the USDA, CDC, or your local extension office about regional outbreaks.

Commercial operations may use vaccination programs where permitted, but backyard flock owners should rely on prevention rather than treatment, as antiviral drugs are not approved for use in food-producing animals.

Regional Variations and Seasonal Trends in Bird Flu Outbreaks

Bird flu activity varies by geography and time of year. In North America, outbreaks tend to spike between late fall and early spring, coinciding with migratory bird patterns. States like Iowa, Minnesota, and California—major poultry producers—have experienced large-scale culling events in past years. Rural areas near lakes or flyways are at higher risk.

Internationally, Asia and Africa have reported recurring H5N1 outbreaks in both poultry and humans. The European Union mandates enhanced surveillance during high-risk periods and imposes movement restrictions when cases are detected.

These regional differences mean that prevention strategies should be tailored to local conditions. Check with your state’s Department of Agriculture or equivalent agency for region-specific guidance on reporting requirements and control zones.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu in Chickens

Several myths persist about avian influenza, leading to delayed responses or unnecessary panic:

- Myth: Only sick-looking birds spread the virus. Truth: Infected birds can shed the virus before showing symptoms.

- Myth: Cooking kills the virus, so eating eggs is always safe. Truth: While proper cooking destroys the virus, infected flocks are typically depopulated, and their products do not enter the food supply.

- Myth: My small backyard flock isn’t at risk. Truth: Even a few chickens can contract the virus via wind-blown particles or contaminated shoes.

- Myth: Vaccinated birds can't get bird flu. Truth: Vaccines reduce severity but don’t eliminate infection or shedding entirely.

- Myth: Humans can't catch bird flu from chickens. Truth: Though rare, H5N1 and other strains have caused human infections, usually through close, unprotected contact.

Legal and Reporting Requirements for Poultry Owners

In the United States, avian influenza is a reportable disease. Federal law requires immediate notification to veterinary authorities upon suspicion. Failure to report can result in fines and increased spread. The USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) leads response efforts, including quarantine, testing, and compensation for depopulated birds in commercial settings.

Backyard flock owners may not receive financial compensation, but they play a critical role in early detection. Many states offer free diagnostic services through land-grant universities or state labs. Always follow official protocols—do not attempt home remedies or unofficial treatments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can humans get bird flu from handling infected chickens?

Yes, though rare, direct contact with infected birds or their droppings can transmit certain strains like H5N1 to humans. Always wear gloves and masks when handling sick or dead poultry, and wash thoroughly afterward.

How long does the bird flu virus survive in the environment?

The virus can persist for up to 30 days in cold, damp conditions like manure or pond water. In dry, warm environments, it may last only a few days.

Is there a vaccine for chickens against bird flu?

Vaccines exist but are tightly regulated. In the U.S., they are generally used only in large commercial operations during outbreaks and require federal approval.

Should I stop eating eggs if bird flu is in my area?

No. Eggs from infected flocks are banned from the market. Commercially sold eggs remain safe, especially when cooked thoroughly.

What happens if my chickens test positive for bird flu?

Officials will likely order depopulation of the entire flock to stop spread. Your premises may be quarantined, and thorough cleaning and disinfection will be required before restocking.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4