One of the most effective ways to protect chickens from bird flu is to implement strict biosecurity practices on your poultry farm or backyard coop. A natural long tail keyword variant such as 'how to keep backyard chickens safe from avian influenza outbreaks' captures the core concern of many small-scale poultry owners. By minimizing exposure to wild birds, controlling access to coops, maintaining hygiene, and monitoring flock health, chicken owners can significantly reduce the risk of avian influenza transmission. These proactive steps are essential in both rural and suburban settings where domestic poultry may come into indirect contact with infected migratory birds.

Understanding Avian Influenza (Bird Flu)

Bird flu, or avian influenza, is a highly contagious viral disease caused by influenza A viruses that primarily affect birds. These viruses are naturally found in wild aquatic birds like ducks, geese, and shorebirds, which often carry the virus without showing symptoms. However, when transmitted to domestic poultryâespecially chickensâit can lead to severe illness and high mortality rates. The two main types of avian influenza are low pathogenic (LPAI) and high pathogenic (HPAI). While LPAI may cause mild respiratory issues, HPAI strains, such as H5N1, can spread rapidly and result in near-total flock loss within days.

The current global concern stems from ongoing outbreaks of HPAI H5N1, which has affected commercial farms and backyard flocks across North America, Europe, and Asia since 2022. According to the USDA and OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health), millions of birds have been culled to prevent further spread. This strain is particularly dangerous because it can jump species barriers, occasionally infecting mammalsâand rarely, humansâthough sustained human-to-human transmission remains extremely rare.

Transmission Pathways: How Birds Spread the Virus

To effectively protect chickens from bird flu, it's critical to understand how the virus spreads. Transmission occurs through direct contact with infected birds or indirect exposure via contaminated environments. Key pathways include:

- Fecal matter from infected wild birds contaminating feed, water, or soil

- Aerosolized particles in enclosed spaces with poor ventilation

- Contaminated equipment, clothing, footwear, or vehicles entering coops

- Predators or scavengers (e.g., raccoons, rats) carrying droppings into enclosures

- Migratory bird flyways overlapping with poultry farming regions

Backyard flock owners often underestimate the risk posed by seemingly harmless interactionsâlike allowing chickens to free-range near ponds frequented by ducks. Even airborne transmission over short distances between adjacent farms has been documented during peak outbreak seasons.

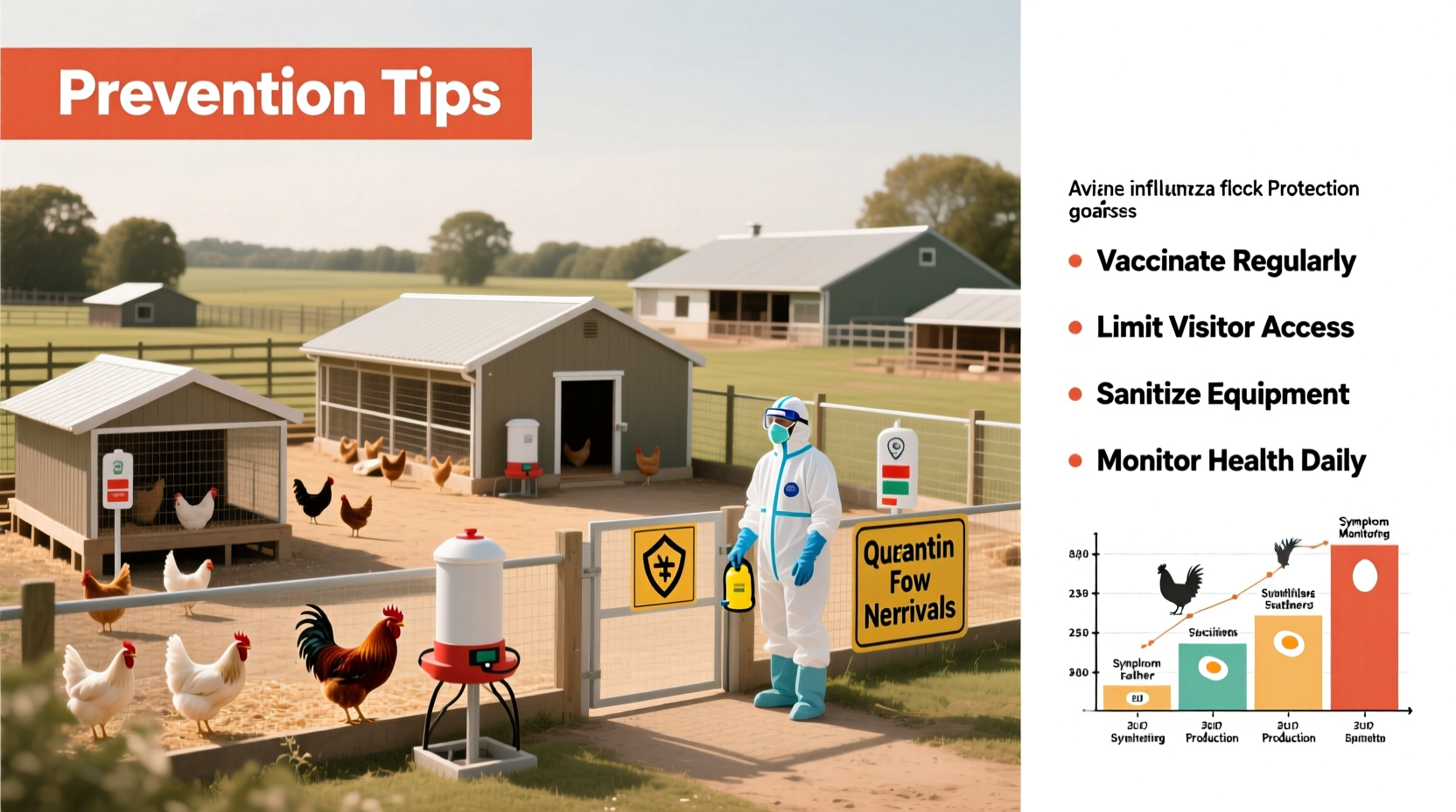

Core Biosecurity Measures to Prevent Bird Flu

Implementing robust biosecurity protocols is the cornerstone of protecting chickens from avian influenza. Below are actionable, science-backed strategies every poultry keeper should adopt:

1. Limit Exposure to Wild Birds

Prevent wild birds from accessing your chickensâ living areas. Cover outdoor runs with netting or wire mesh to block entry. Avoid placing feeders or water sources outdoors where they can attract wild birds. If possible, house chickens indoors during peak migration periods (typically fall and spring).

2. Control Human and Vehicle Access

Restrict visitors to your coop area. Anyone entering must wear dedicated footwear and clean outerwear. Provide disinfectant footbaths at coop entrances. Vehicles used for transporting feed or eggs should not travel directly from other poultry sites without thorough cleaning.

3. Practice Rigorous Hygiene

Clean and disinfect coops weekly using approved agents like bleach solutions (1:10 dilution), Virkon-S, or agricultural-grade quaternary ammonium compounds. Remove soiled bedding daily. Wash hands before and after handling birds. Never share tools or equipment with other poultry owners without sterilization.

4. Source Birds Responsibly

Only acquire chickens from reputable hatcheries or suppliers that test for avian diseases. Quarantine new birds for at least 30 days before introducing them to an existing flock. Monitor quarantined birds closely for signs of lethargy, decreased appetite, nasal discharge, or reduced egg production.

5. Secure Feed and Water Supplies

Store feed in sealed, rodent-proof containers. Use covered waterers to prevent contamination. Change water daily and clean containers regularly. Avoid using open troughs that wild birds can access.

Vaccination: Is It an Option?

In some countries, vaccination against specific strains of avian influenza is permitted and widely used. However, in the United States, routine vaccination of backyard or commercial flocks is currently not approved by the USDA due to concerns about surveillance and trade implications. Vaccinated birds may still carry and shed the virus without showing symptoms, making detection harder. That said, research is ongoing, and emergency vaccination may be deployed during large-scale outbreaks under federal oversight.

If you're located outside the U.S.âsuch as in parts of Europe or Asiaâcheck with local veterinary authorities about available vaccines. Even in vaccinated flocks, biosecurity remains essential. No vaccine offers 100% protection, especially against rapidly mutating strains.

Monitoring and Early Detection

Early recognition of bird flu symptoms can save lives and prevent wider outbreaks. Common clinical signs in infected chickens include:

- Sudden death without prior symptoms

- Loss of appetite and energy

- Swelling around the eyes, neck, or head

- Purple discoloration of wattles, combs, or legs

- Respiratory distress (coughing, sneezing, gasping)

- Marked drop in egg production or soft-shelled eggs

If you observe any of these signs, immediately isolate sick birds and contact your veterinarian or state animal health official. Report suspected cases to national hotlines such as the USDAâs toll-free number (1-866-536-7593) or use online reporting systems like eNAHSS (Electronic National Animal Health Surveillance System).

Regional Differences and Seasonal Patterns

Risk levels vary by region and season. Areas along major migratory flywaysâsuch as the Mississippi Flyway in the U.S.âexperience higher spillover risks during spring and fall migrations. States like Iowa, Minnesota, and California have seen repeated commercial flock infections. Urban and suburban coops are not immune; wind-blown particulates or contaminated materials can introduce the virus even in densely populated areas.

Local regulations may differ. Some states mandate registration of flocks above a certain size or require movement permits during outbreak alerts. Always verify current guidelines through your stateâs Department of Agriculture website or extension office. For example, during a declared outbreak, restrictions may be placed on poultry shows, swaps, and exhibitions.

| Prevention Strategy | Effectiveness | Cost Level | Implementation Difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coop Netting/Covering Runs | High | Low-Medium | Easy |

| Footbaths & Disinfection | Medium-High | Low | Moderate |

| Quarantine New Birds | High | Low | Easy |

| Vaccination (where allowed) | Variable | High | Difficult |

| Indoor Housing During Migration | Very High | Medium | Moderate |

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu and Chickens

Several myths persist about avian influenza and backyard poultry:

- Myth: Only large farms get bird flu.

Fact: Backyard flocks are equally vulnerable, especially if they free-range near wetlands. - Myth: Cooking eggs or meat kills the virus, so thereâs no need to worry.

Fact: While proper cooking does destroy the virus, the primary goal is preventing infection in live birds to avoid economic loss and public health alerts. \li>Myth: Organic or free-range chickens are more resistant. - Myth: If my birds look healthy, theyâre safe.

Fact: Infected birds can be asymptomatic carriers, shedding virus before showing illness.

Fact: There is no evidence that diet or housing type confers immunity. All chickens are susceptible.

Preparing for an Outbreak: Emergency Planning

Every chicken owner should have a preparedness plan. Steps include:

- Keeping a list of emergency contacts: vet, state animal health office, USDA representative

- Storing extra feed, water, and disinfectants

- Designating an isolation area for sick birds

- Documenting flock size, breed, and health records

- Signing up for alert systems like USDA APHIS email updates or local ag extension notifications

In the event of a confirmed outbreak nearby, authorities may impose quarantine zones, restrict bird movement, or recommend depopulation. Cooperate fully with officials to limit regional spread.

Impact on Egg Production and Consumption

During bird flu outbreaks, egg availability may decrease due to mass culling of laying hens. Prices often rise temporarily. Consumers sometimes fear eating eggs from infected areas, but regulatory agencies ensure that contaminated products do not enter the food supply. Eggs from depopulated flocks are destroyed, and surviving commercial operations undergo rigorous testing.

For backyard keepers, continue collecting eggs only if birds appear healthy and no local bans are in place. Wash eggs thoroughly before use. There is no evidence of transmission through properly handled and cooked eggs.

FAQs: Frequently Asked Questions

- Can humans catch bird flu from handling chickens?

- While rare, human infections have occurred, usually through prolonged, close contact with infected birds. Wear gloves and masks when handling sick animals and wash hands thoroughly.

- Should I stop letting my chickens free-range?

- During active bird flu outbreaks in your region, itâs safest to keep chickens confined indoors or under covered runs to minimize exposure to wild bird droppings.

- Are ducks more likely to spread bird flu than chickens?

- Yes. Ducks and other waterfowl often carry the virus without getting sick, making them silent spreaders. Keep them separated from chickens if possible.

- How often should I disinfect my coop?

- Perform deep cleaning and disinfection weekly. Daily removal of manure and soiled bedding reduces pathogen load.

- Is there a home test for bird flu in chickens?

- No reliable at-home test exists. Suspected cases require laboratory analysis via swabs sent to certified veterinary labs.

Protecting chickens from bird flu requires vigilance, education, and consistent action. Whether you manage a single backyard flock or a larger operation, adopting strong biosecurity habits dramatically lowers the risk of infection. Stay informed through trusted sources like the USDA, CDC, and local agricultural extensions, and act quickly at the first sign of trouble. With proper care and prevention, you can help safeguard your birds, your community, and the broader poultry industry from the threat of avian influenza.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4