Bird flu, or avian influenza, is a viral infection that primarily affects birds but can occasionally spread to humans. To protect yourself from bird flu, avoid direct contact with wild or domestic birds, especially sick or dead ones, practice thorough handwashing after any potential exposure, and ensure poultry and eggs are properly cooked before consumption. These measures form the cornerstone of personal protection against avian influenza transmission.

Understanding Bird Flu: Origins and Transmission

Bird flu is caused by strains of the influenza A virus, most commonly subtypes H5N1, H7N9, and H5N8. These viruses naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds such as ducks and geese, which often carry the virus without showing symptoms. However, when transmitted to domestic poultry like chickens and turkeys, the disease can become highly pathogenic, leading to rapid outbreaks and high mortality rates in flocks.

Human infections are rare but occur primarily through close contact with infected birds or contaminated environments—such as live bird markets, farms, or areas where bird droppings accumulate. The virus does not currently spread efficiently between people, which limits large-scale human outbreaks. However, public health officials remain vigilant due to the potential for the virus to mutate into a form that could transmit easily among humans, potentially triggering a pandemic.

Historical Context and Global Outbreaks

The first known human case of H5N1 was reported in Hong Kong in 1997. Since then, sporadic cases have occurred across Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America. Notable outbreaks include:

- 2003–2006: Widespread H5N1 outbreak across Southeast Asia affecting millions of birds and resulting in over 300 human cases.

- 2013: Emergence of H7N9 in China, linked to live poultry markets; more than 1,500 human cases recorded, with high fatality rate.

- 2022–2024: Unprecedented global spread of H5N1 in wild birds and poultry, detected in over 70 countries including the United States, the UK, Germany, and Japan.

In 2022, the U.S. Department of Agriculture confirmed the largest bird flu outbreak in American history, affecting more than 58 million birds across 47 states. This resurgence has heightened awareness about zoonotic risks and reinforced the need for preventive strategies among both farmers and the general public.

Who Is at Risk?

While anyone can be exposed, certain groups face higher risk of infection:

- Poultry farm workers and backyard flock owners

- Veterinarians and animal health inspectors

- Workers at live bird markets

- Hunters handling wild waterfowl

- Travelers visiting regions experiencing active outbreaks

Children and individuals with weakened immune systems may also experience more severe illness if infected. Although human-to-human transmission remains extremely limited, prolonged close contact with an infected person (e.g., household caregivers) poses a theoretical risk.

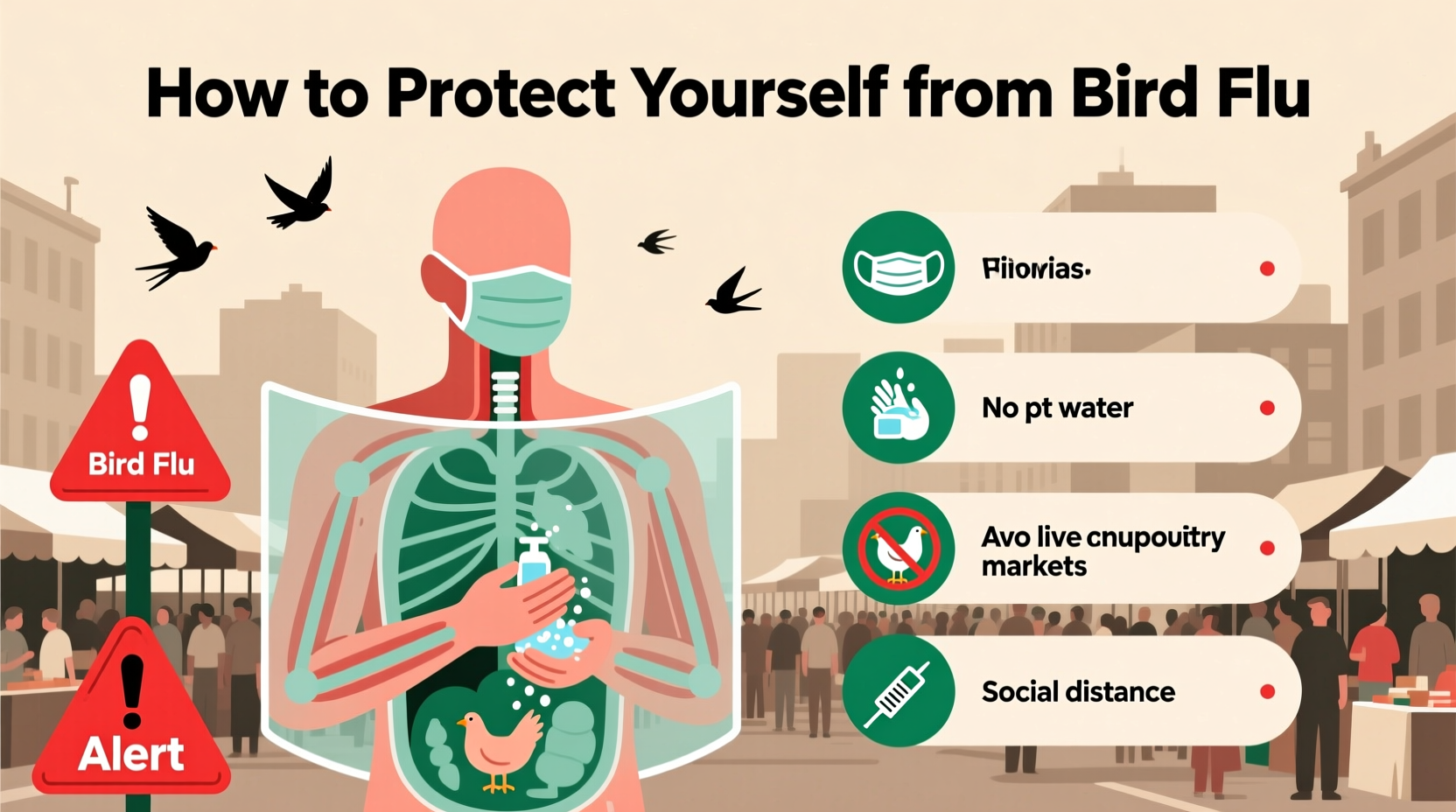

Practical Steps to Protect Yourself from Bird Flu

Preventing bird flu involves a combination of personal hygiene, food safety practices, and situational awareness. Below are evidence-based recommendations:

Avoid Contact with Sick or Dead Birds

Never touch or handle dead, injured, or visibly ill birds. If you find a dead bird—especially waterfowl, raptors, or multiple birds in one location—report it to your local wildlife agency or department of natural resources. In the U.S., state agencies often provide online reporting tools or hotlines for this purpose.

Practice Good Hand Hygiene

Wash hands thoroughly with soap and water for at least 20 seconds after being outdoors, especially after visiting areas where birds congregate (e.g., parks, lakes, farms). Use alcohol-based hand sanitizer (at least 60% alcohol) when soap and water aren’t available.

Use Protective Equipment When Handling Birds

If you work with or care for poultry, wear gloves, masks, and protective clothing. After handling birds or cleaning coops, disinfect tools and surfaces using a bleach solution (1 part bleach to 9 parts water) or EPA-registered disinfectants effective against influenza viruses.

Cook Poultry and Eggs Thoroughly

Avian influenza viruses are destroyed by heat. Always cook poultry to an internal temperature of at least 165°F (74°C), and ensure egg yolks and whites are fully firm. Avoid consuming raw or undercooked eggs, especially in dishes like homemade mayonnaise or uncooked cookie dough.

Stay Informed During Outbreaks

Monitor updates from trusted sources such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), or national health departments. Travelers should check advisories before visiting regions with ongoing bird flu activity.

| Prevention Strategy | Description | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Avoid bird contact | No handling of live, sick, or dead birds | High |

| Handwashing | Soap and water after outdoor exposure | High |

| Cooking safety | Cook poultry >165°F, eggs until firm | Very High |

| Personal protective equipment (PPE) | Gloves, masks for bird handlers | Moderate to High |

| Vaccination (for poultry) | Limits spread in flocks | Variable |

Myths and Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several misconceptions persist about how bird flu spreads and who is at risk:

- Myth: You can get bird flu from eating properly cooked chicken.

Fact: No—cooking destroys the virus. Only undercooked meat poses a risk. - Myth: Bird flu spreads easily between people.

Fact: Sustained human-to-human transmission has not been documented. - Myth: All bird species carry the virus equally.

Fact: Wild waterfowl are primary reservoirs; songbirds and raptors rarely shed high levels. - Myth: There’s nothing governments can do to control outbreaks.

Fact: Culling infected flocks, biosecurity enforcement, and surveillance help contain spread.

Regional Differences in Risk and Response

Risk levels vary significantly depending on geography and agricultural practices. In rural areas of Southeast Asia, where backyard poultry farming is common and live bird markets operate frequently, human exposure risk is elevated. In contrast, North America and Western Europe have stronger biosecurity standards, though recent increases in wild bird infections have raised concerns.

In the U.S., the USDA and CDC collaborate on monitoring programs, including testing migratory birds and commercial flocks. Some states restrict bird gatherings (e.g., fairs, shows) during peak migration seasons. Similarly, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) issues seasonal risk assessments based on migration patterns.

Travelers should research local conditions before visiting affected regions. For example, during an active outbreak, Chinese authorities may temporarily close live poultry markets—a measure shown to reduce human cases dramatically.

What to Do If Exposed

If you’ve had close contact with a confirmed infected bird or environment, monitor yourself for symptoms for up to 10 days. Common signs include:

- Fever (>100.4°F / 38°C)

- Cough

- Sore throat

- Muscle aches

- Shortness of breath

If symptoms develop, seek medical attention immediately and inform your healthcare provider about the exposure. Antiviral medications like oseltamivir (Tamiflu) may be prescribed early to reduce severity and duration of illness.

Public health departments may recommend quarantine or prophylactic antivirals for high-risk exposures, particularly among healthcare workers or household contacts.

Vaccines and Future Preparedness

There is currently no widely available seasonal vaccine for bird flu in humans, unlike regular flu shots. However, candidate vaccines for H5N1 and H7N9 have been developed and stockpiled by some governments for emergency use during outbreaks.

Seasonal flu vaccination is still recommended, as it reduces the chance of dual infection (human and avian flu), which could allow genetic reassortment and lead to a new pandemic strain.

Researchers continue to develop universal influenza vaccines that could offer broader protection across strains, potentially reducing future zoonotic threats.

Role of Birdwatchers and Nature Enthusiasts

Birdwatching is a popular hobby worldwide, but enthusiasts must take precautions during outbreaks. Recommendations include:

- Maintain distance from birds—use binoculars instead of approaching nests or roosts.

- Avoid feeding wild birds in areas with known outbreaks.

- Do not touch nesting materials or droppings.

- Clean binoculars, cameras, and footwear after visits to wetlands or reserves.

- Report unusual bird deaths to local conservation groups.

Organizations like the Audubon Society and Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) issue alerts during heightened surveillance periods and encourage ethical observation practices.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Can I get bird flu from my pet parrot?

No. Companion birds like parrots, canaries, and budgies are not known to transmit avian influenza to humans under normal circumstances. - Is it safe to visit zoos or aviaries?

Yes, most facilities follow strict biosecurity protocols. However, avoid touching enclosures or feeding birds directly. - Does wearing a mask protect me from bird flu?

Surgical or N95 masks can reduce inhalation risk when working with infected birds, but are unnecessary for casual outdoor activities. - Are migratory birds responsible for spreading bird flu?

Yes. Wild waterfowl, especially ducks and geese, carry the virus over long distances during migration, introducing it to new regions. - Can dogs or cats get bird flu?

Rare cases have occurred, usually after consuming infected birds. Keep pets away from sick or dead wildlife.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4