If you're wondering how to tell if your chickens have bird flu, the key is recognizing sudden and severe symptoms such as a rapid drop in egg production, swelling of the head and neck, purple discoloration on combs and wattles, nasal discharge, coughing, sneezing, diarrhea, and sudden death. One of the most telling signs—especially in backyard flocks—is a noticeable decline in activity or birds appearing 'off' without clear cause. Monitoring your flock daily for behavioral and physical changes is essential when trying to determine how to identify bird flu in chickens, particularly during outbreaks reported in your region.

Understanding Avian Influenza: What It Is and How It Spreads

Bird flu, or avian influenza (AI), is a highly contagious viral infection caused by influenza A viruses that primarily affect birds. While there are many strains, the ones of greatest concern are the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) types, especially H5N1, which can spread rapidly among poultry and result in high mortality rates. These viruses are naturally found in wild aquatic birds like ducks and geese, which often carry the virus without showing symptoms, making them silent transmitters to domestic flocks.

The virus spreads through direct contact with infected birds, their droppings, or contaminated surfaces such as feeders, waterers, shoes, clothing, and equipment. Airborne transmission over short distances is also possible, especially in enclosed coops. Because of this, biosecurity is not just a recommendation—it's a necessity for any chicken keeper, whether managing a small backyard coop or a commercial operation.

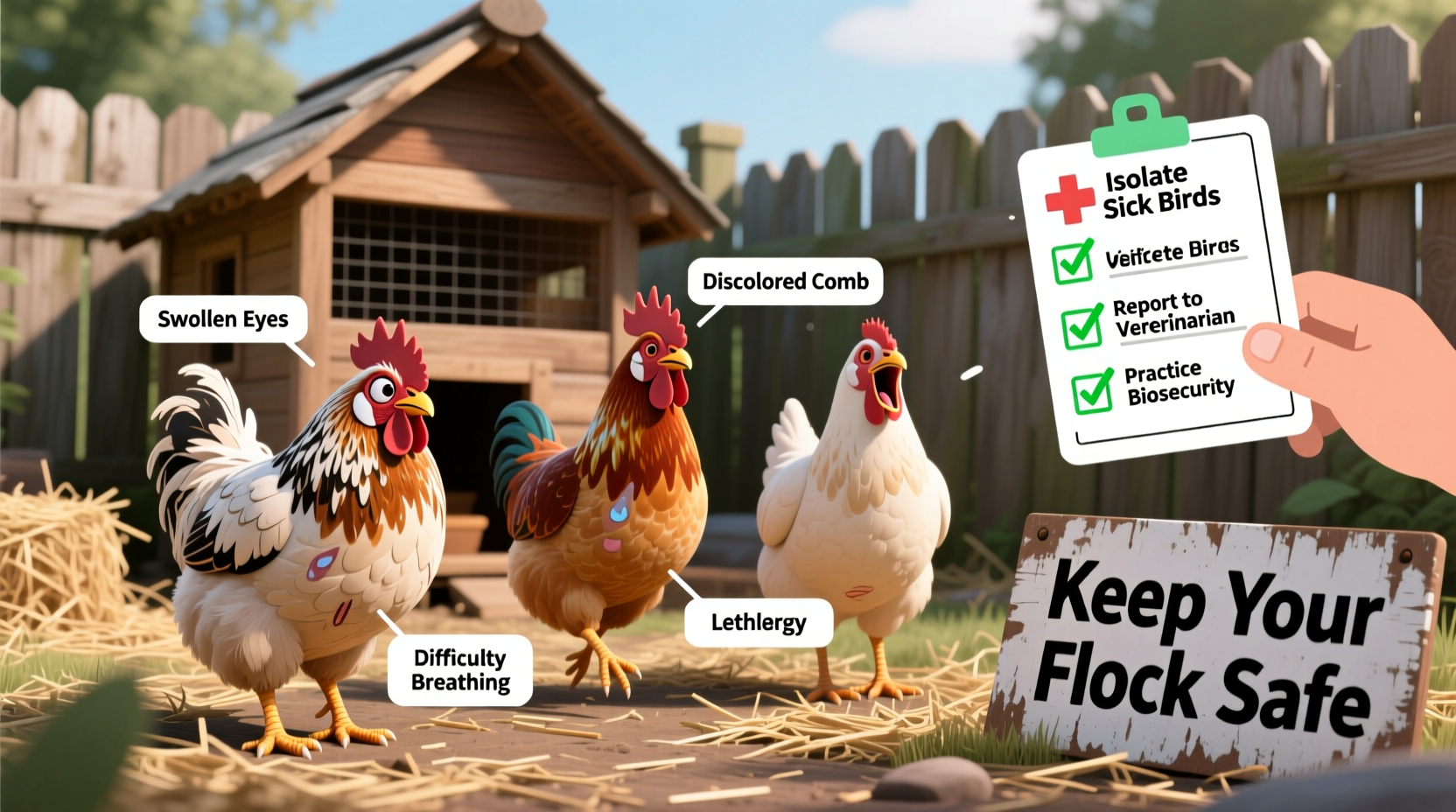

Early Warning Signs: Behavioral and Physical Indicators

Recognizing the early signs of bird flu in your chickens can mean the difference between containment and widespread loss. Chickens are prey animals and instinctively hide illness until they are very sick. Therefore, subtle changes in behavior should be taken seriously.

- Lethargy: Birds may sit hunched, appear sleepy, or stop moving around normally.

- Reduced appetite: Sudden disinterest in food or water.

- Drop in egg production: A sharp decline—or complete halt—in laying within days.

- Respiratory distress: Gurgling sounds, gasping, or open-mouth breathing.

- Swelling: Especially around the eyes, comb, wattles, and legs.

- Neurological signs: Tremors, twisted necks, lack of coordination.

- Sudden death: Sometimes the first and only sign, particularly with HPAI.

It's important to note that some of these symptoms can resemble other diseases like Newcastle disease or infectious bronchitis. However, the speed and severity of onset—with multiple birds affected quickly—are strong indicators of avian influenza.

Differentiating Bird Flu from Common Poultry Illnesses

Many backyard chicken owners may mistake bird flu symptoms for more common ailments. For example, respiratory infections caused by bacteria or mites can lead to sneezing and nasal discharge. Internal parasites might cause lethargy and weight loss. But bird flu typically presents a combination of symptoms across multiple systems—respiratory, digestive, neurological, and reproductive—all at once.

Unlike coccidiosis, which mainly affects young chicks and causes bloody diarrhea, bird flu impacts birds of all ages and includes external swelling and discoloration. Also, while molting can cause a drop in egg production, it doesn’t come with respiratory issues or sudden deaths. Understanding these distinctions helps prevent panic but also ensures timely action when necessary.

What to Do If You Suspect Bird Flu in Your Flock

If you observe several of the above symptoms—especially sudden deaths combined with swelling or respiratory signs—you must act immediately. Here’s a step-by-step guide:

- Isolate sick birds: Separate any showing symptoms from the rest of the flock to reduce transmission.

- Stop all movement: Do not move birds, eggs, manure, or equipment off your property.

- Contact authorities: In the U.S., call the USDA toll-free hotline at 1-866-536-7593 or your state veterinarian. Reporting is mandatory and helps track outbreaks.

- Practice strict biosecurity: Wear gloves and masks, disinfect boots and tools, and avoid visiting other flocks.

- Wait for testing: A lab test is required to confirm bird flu. Nasal, throat, or cloacal swabs are collected by professionals.

Do not attempt to treat bird flu with antibiotics—this is a virus, not a bacterial infection. Antivirals are not used in poultry, and there is no approved cure. The focus is on containment and preventing further spread.

Prevention: Biosecurity Measures Every Chicken Owner Should Take

Preventing bird flu starts with strong biosecurity practices. Whether you have five hens or fifty, here are proven strategies to protect your flock:

- Limit exposure to wild birds: Cover outdoor runs with netting, remove bird feeders nearby, and avoid letting chickens free-range in areas frequented by waterfowl.

- Control human traffic: Require visitors to wear clean clothes and footwear. Provide disposable boot covers or footbaths with disinfectant.

- Clean and disinfect regularly: Use veterinary-grade disinfectants on coops, feeders, and waterers weekly.

- Quarantine new birds: Keep newcomers isolated for at least 30 days and monitor for illness.

- Avoid sharing equipment: Don’t loan out or borrow crates, feeders, or tools from other poultry owners.

- Monitor local alerts: Sign up for notifications from your state agriculture department or USDA about bird flu detections in your area.

Regional Differences and Seasonal Patterns

Bird flu risk varies by region and season. In North America, outbreaks are more common in late fall and winter, coinciding with wild bird migration patterns. States in the Central and Mississippi flyways—such as Minnesota, Iowa, and California—have experienced major outbreaks in recent years. However, no area is immune. Even urban backyard flocks in states with low poultry density have tested positive after exposure to infected wild birds.

International travelers should also be cautious. Countries with ongoing outbreaks may restrict the import of poultry products or live birds. Always check current advisories before bringing anything related to birds across borders.

Legal and Regulatory Considerations

In the U.S., avian influenza is a federally reportable disease. If your flock tests positive, officials may order depopulation to prevent further spread. While this is devastating, compensation programs may be available through the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) for commercial operations. Backyard flock owners may receive limited or no compensation, so prevention is even more critical.

Additionally, movement restrictions will be imposed. You may not be able to show birds, sell eggs, or transport poultry until the quarantine is lifted, which can take weeks or months. Staying compliant with regulations protects not only your flock but the broader agricultural community.

Myths and Misconceptions About Bird Flu in Chickens

Several myths persist about bird flu that can lead to poor decisions:

- Myth: Only large farms get bird flu. Truth: Backyard flocks are just as vulnerable, especially if they interact with wild birds.

- Myth: Cooking kills the virus, so I can still eat the eggs. While heat destroys the virus, consuming eggs from infected birds is unsafe due to potential contamination and ethical concerns.

- Myth: Vaccination is widely available for backyard chickens. Currently, vaccines are not commercially available for small flocks in the U.S. and are mainly used in controlled settings abroad.

- Myth: If one bird dies, it’s just natural. In the context of a known regional outbreak, any unexplained death should be investigated.

How Often Should You Check Your Chickens for Bird Flu Symptoms?

Daily observation is the best defense. Spend a few minutes each morning watching your birds move, eat, and behave. Learn their normal routines so you can spot deviations quickly. During high-risk periods—like fall migration or when local cases are confirmed—consider doing two checks per day.

Keep a simple log noting egg production, appetite, and any abnormalities. This record can be invaluable if you need to report symptoms to a veterinarian or official agency.

Resources and Support for Poultry Owners

Staying informed is part of responsible ownership. Reliable sources include:

- USDA APHIS Avian Influenza website

- Your state’s department of agriculture

- Local cooperative extension offices

- Poultry veterinarian networks

Many states offer free webinars, fact sheets, and biosecurity kits. Some even have mobile apps that alert you to nearby outbreaks.

| Symptom | Common in Bird Flu? | Also Seen In |

|---|---|---|

| Sudden death | Yes (HPAI) | Predation, poisoning |

| Swollen head/comb | Yes | Frostbite, injury |

| Drop in egg production | Yes | Molting, stress, age |

| Diarrhea | Yes | Parasites, diet change |

| Nasal discharge | Yes | CRD, mycoplasma |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can humans get bird flu from chickens?

While rare, certain strains like H5N1 can infect humans, usually through close, prolonged contact with sick birds. Always wear protective gear when handling ill poultry.

Is it safe to eat eggs from a flock with bird flu?

No. Even though cooking kills the virus, consumption is not recommended due to health risks and legal restrictions during outbreaks.

How long does bird flu survive in the environment?

The virus can live for days in feces and water, and up to two weeks in cool, damp conditions. Proper disinfection is crucial.

Are certain chicken breeds more resistant to bird flu?

No scientific evidence shows breed resistance. All chickens are susceptible regardless of type.

What happens if my flock tests positive?

Authorities will likely require depopulation, disposal, and deep cleaning of the premises. Movement restrictions will follow to prevent spread.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4