Bird flu, or avian influenza, is a viral infection that primarily affects birds but can occasionally infect humans and other animals. Understanding how to treat bird flu involves both medical intervention and preventive strategies, especially for poultry farmers, wildlife handlers, and individuals in close contact with birds. A key long-tail keyword variant related to this topic is 'what are the best methods to manage bird flu outbreaks in poultry.' The treatment of bird flu focuses not on curing infected birds—since there is no widely approved cure—but on containment, biosecurity, vaccination where available, and supportive care in rare human cases.

Understanding Bird Flu: Causes and Transmission

Bird flu is caused by influenza A viruses, which naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds like ducks and shorebirds. These species often carry the virus without showing symptoms, making them silent carriers. The virus spreads through saliva, nasal secretions, and feces. Domestic poultry, such as chickens and turkeys, are highly susceptible and can experience rapid, fatal outbreaks.

The most concerning strains for public health include H5N1, H7N9, and H5N8. While human infections remain rare, they can occur through direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environments. There is currently no sustained human-to-human transmission, but the potential for mutation raises global health concerns.

Can Humans Get Bird Flu? Symptoms and Treatment in People

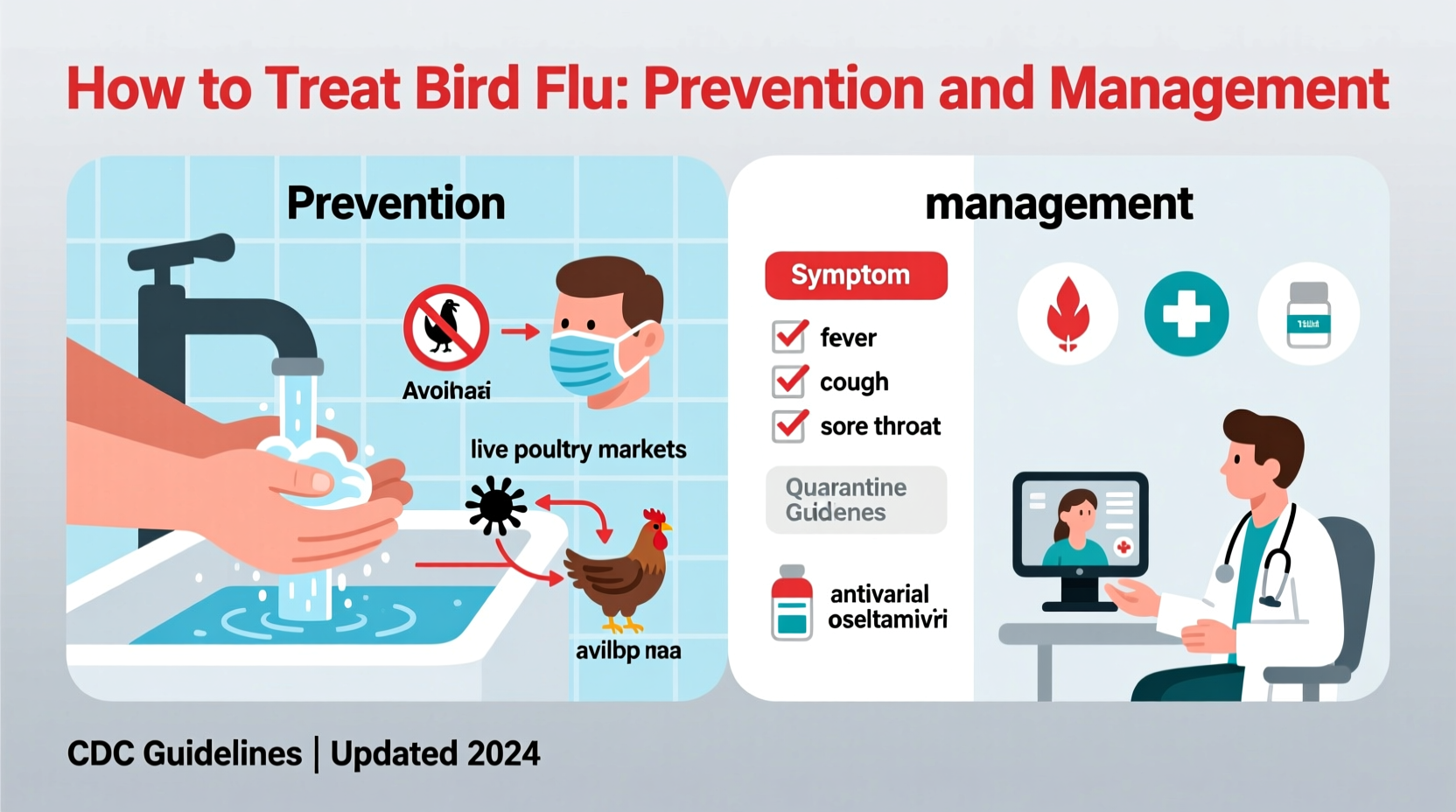

Yes, although uncommon, humans can contract bird flu. Most cases have been reported in individuals who work closely with infected poultry, such as farm workers or live market vendors. Symptoms in humans resemble severe influenza: high fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, and in serious cases, pneumonia and acute respiratory distress.

Treatment for human cases typically involves antiviral medications like oseltamivir (Tamiflu) or zanamivir (Relenza), especially when administered early. These drugs do not eliminate the virus completely but can reduce severity and duration. In critical cases, hospitalization and respiratory support may be necessary. Public health authorities recommend prompt medical evaluation for anyone with bird exposure and flu-like symptoms.

Managing Bird Flu in Poultry: No Cure, But Control Is Possible

There is no specific cure for bird flu in birds. Once an outbreak occurs in a flock, the standard response is culling—humanely euthanizing infected and exposed birds to prevent further spread. This method, while drastic, remains the most effective way to contain the virus.

Vaccination is another tool used in some countries. However, vaccines do not always prevent infection; instead, they reduce viral shedding and disease severity. Challenges include the need for strain-specific vaccines and the risk of masking infections in vaccinated flocks. Regulatory agencies like the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) emphasize that vaccination should complement, not replace, strong biosecurity measures.

Prevention Through Biosecurity: Best Practices for Farms and Backyard Flocks

Preventing bird flu starts with strict biosecurity protocols. These are essential for commercial farms and backyard bird owners alike. Key practices include:

- Limiting access to poultry areas by visitors and vehicles

- Using dedicated clothing and footwear for handling birds

- Disinfecting equipment and coops regularly

- Isolating new birds for at least 30 days before introducing them to a flock

- Preventing contact between domestic birds and wild birds or their droppings

Farmers should also monitor flocks daily for signs of illness, such as decreased egg production, swollen heads, or sudden death. Early detection allows quicker response and reduces economic loss.

Wildlife Surveillance and Government Response

National and international agencies play a crucial role in tracking bird flu. In the United States, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collaborate on surveillance, testing, and response efforts. Globally, WOAH collects data from member countries to detect emerging strains.

When an outbreak is confirmed, governments may impose movement restrictions, ban live bird markets temporarily, or fund compensation programs for culled flocks. Timely reporting and transparency are vital to controlling cross-border spread, especially during migratory seasons when wild birds travel across continents.

Public Health Recommendations During Outbreaks

During active bird flu outbreaks, public health officials issue guidance to minimize risk. Recommendations include avoiding contact with sick or dead birds, using gloves and masks when handling poultry, and thoroughly cooking eggs and meat to kill any virus present. The CDC advises against home slaughter of birds from affected areas.

In regions with known human cases, enhanced monitoring and travel advisories may be issued. Although the general public faces low risk, those with occupational exposure should receive training and protective gear. Rapid diagnostic tests help identify cases quickly, enabling timely isolation and treatment.

Regional Differences in Bird Flu Management

Approaches to managing bird flu vary by region due to differences in agriculture, climate, and regulatory frameworks. In Southeast Asia, where backyard farming is common and live bird markets widespread, control is more challenging. Countries like Vietnam and Indonesia have implemented mass vaccination campaigns alongside education programs.

In contrast, North America and Western Europe rely heavily on surveillance and rapid culling. The European Union has strict regulations requiring immediate reporting of suspected cases. In Africa, limited veterinary infrastructure can delay responses, increasing the risk of undetected spread.

Climate also influences transmission patterns. Cold temperatures allow the virus to survive longer in the environment, increasing winter risks. Migratory flyways connect regions across hemispheres, meaning an outbreak in one country can affect others months later.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about bird flu. One is that eating properly cooked poultry or eggs can transmit the virus. This is false—the virus is destroyed at temperatures above 70°C (158°F). Another misconception is that bird flu spreads easily among humans. As of now, sustained human-to-human transmission has not occurred.

Some believe that all bird deaths indicate bird flu. In reality, many diseases and environmental factors cause bird mortality. Laboratory testing is required for confirmation. Lastly, some think vaccines eliminate the need for biosecurity. On the contrary, vaccines are just one layer of defense.

What Should You Do If You Find a Dead Bird?

If you encounter a dead wild bird, especially waterfowl or raptors, do not touch it with bare hands. Contact local wildlife authorities or your state’s department of natural resources. They may collect the carcass for testing, particularly during known outbreaks.

In urban areas, municipal services often handle disposal. Always wash hands after outdoor activities near birds. Pet owners should keep cats and dogs away from dead birds, as indirect transmission is possible.

Future Outlook: Research and Global Preparedness

Ongoing research aims to develop universal avian influenza vaccines and faster diagnostic tools. Scientists are studying virus evolution to predict which strains might jump to humans. International cooperation through organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) helps coordinate pandemic preparedness.

Early warning systems using satellite tracking of bird migrations and AI-driven data analysis are being tested. These innovations could provide advance alerts to high-risk areas, allowing preemptive protective actions.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Primary Hosts | Wild waterfowl (ducks, geese, swans) |

| High-Risk Domestic Birds | Chickens, turkeys, quail |

| Human Transmission Risk | Low; requires close contact with infected birds |

| Treatment in Humans | Antivirals (e.g., oseltamivir), supportive care |

| Treatment in Birds | No cure; culling and biosecurity are primary responses |

| Prevention Strategy | Biosecurity, surveillance, targeted vaccination |

| Cooking Safety | Properly cooked poultry and eggs are safe to eat |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can bird flu be treated naturally in chickens?

No, there is no proven natural cure for bird flu in chickens. Supportive care does not stop viral spread, and infected flocks are usually culled to protect other birds.

Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

There is no commercially available human vaccine for bird flu, but candidate vaccines exist for stockpiling in case of a pandemic.

How long does the bird flu virus survive in the environment?

The virus can survive in cool, moist conditions for up to several weeks, especially in water and manure.

Can pets get bird flu?

Rarely, cats have been infected after eating infected birds. Dogs are less susceptible, but caution is advised during outbreaks.

What should backyard chicken owners do during a bird flu alert?

They should keep birds indoors, avoid sharing equipment with other farms, enhance sanitation, and report any illness to local veterinary authorities immediately.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4