Bird poop is typically not solid black, but it can appear dark or blackish depending on a bird's diet and health. The color of bird droppings primarily comes from a combination of fecal matter and uric acid, which forms the white, chalky part. The darker portion—often mistaken for being entirely black—is actually the bird’s feces, which may range from green to brown to nearly black based on what the bird has eaten. For instance, birds that consume large quantities of berries, insects, or iron-rich foods may produce droppings with a darker hue, sometimes appearing black under certain lighting conditions. So, while is bird poop black might seem like a simple yes-or-no question, the reality involves a nuanced understanding of avian digestion, diet, and excretion biology.

The Biology Behind Bird Droppings

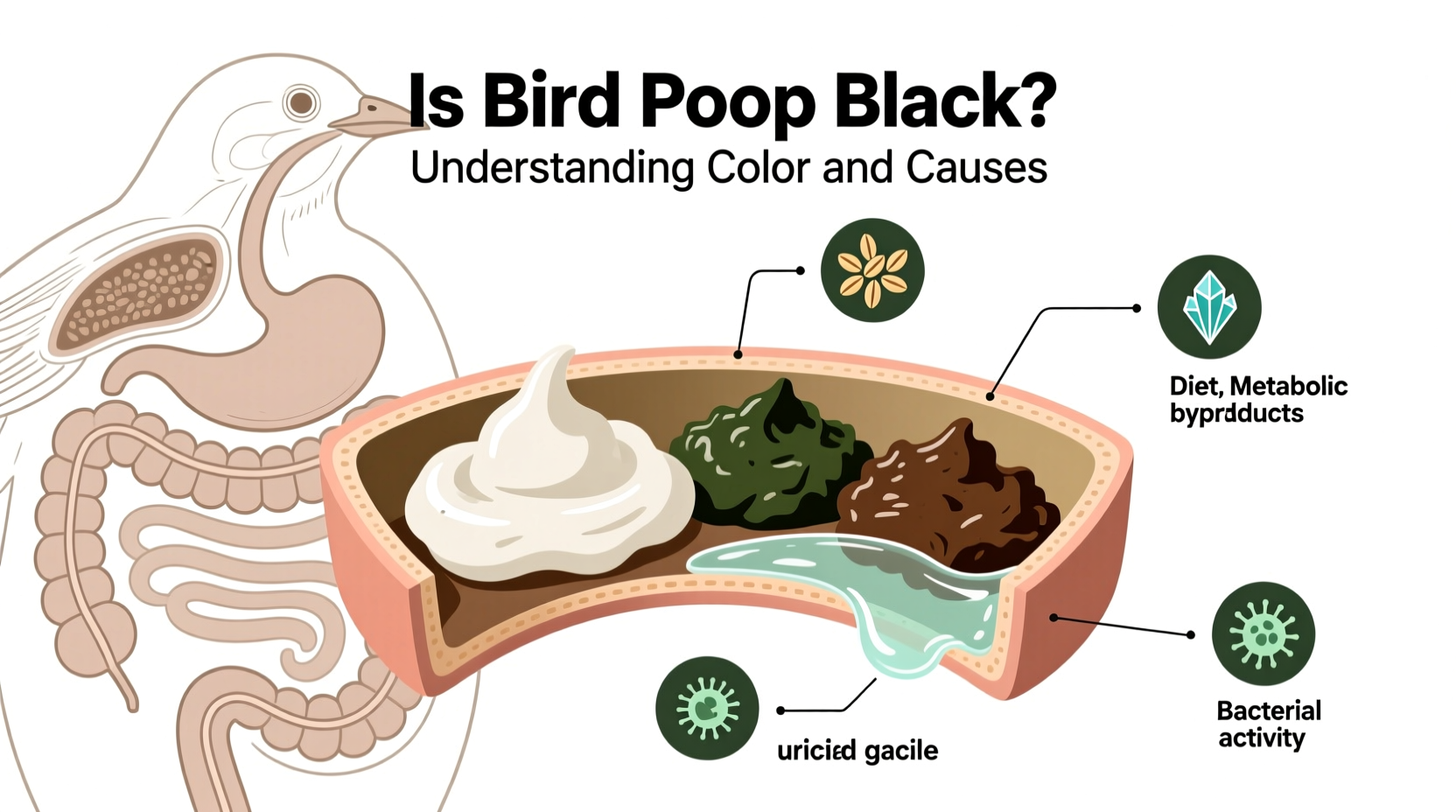

Birds have a unique excretory system compared to mammals. Unlike humans and other mammals, birds do not urinate and defecate separately. Instead, they expel both waste products through a single opening called the cloaca. This results in a combined dropping consisting of three components: fecal matter (the dark part), uric acid (the white paste), and occasionally clear liquid (excess water).

The dark portion of bird poop—the fecal component—is derived from digested food passing through the bird’s short digestive tract. Its color depends heavily on diet. Seed-eating birds like sparrows or pigeons often produce greenish or brown droppings because seeds contain pigments that break down into these colors during digestion. In contrast, birds that feed on fruits rich in anthocyanins—such as mulberries, elderberries, or juniper berries—can produce droppings so dark they appear almost black.

In some cases, particularly when birds consume blood-based diets (like insectivorous species eating iron-rich beetles) or are exposed to environmental contaminants, their droppings may also darken significantly. However, consistently black or tarry droppings could indicate internal bleeding in the upper gastrointestinal tract, a condition known as melena. This warrants veterinary attention in captive birds and may signal health issues in wild populations if observed frequently.

Dietary Influence on Dropping Color

One of the most significant factors affecting whether bird poop looks black is diet. To understand this better, consider the following common dietary categories and their effects:

- Granivores (seed eaters): Birds such as finches, doves, and house sparrows usually produce greenish-brown fecal matter due to chlorophyll breakdown in seeds.

- Frugivores (fruit eaters): Species like thrushes, toucans, and waxwings often have very dark droppings after consuming dark-colored fruits. Mulberry-fed birds, for example, are notorious for leaving near-black stains on sidewalks and cars.

- Insectivores (insect eaters): Swallows, warblers, and flycatchers tend to have droppings ranging from gray to dark brown. High chitin content in insect exoskeletons contributes to this shade.

- Carnivores (meat eaters): Raptors like hawks and owls produce white urates with darker, often mottled fecal portions. Their droppings are rarely uniformly black unless diseased.

- Omnivores: Urban-adapted birds like crows, gulls, and starlings have highly variable dropping colors due to diverse diets, including human food scraps, which can introduce artificial dyes leading to unusual colors—including blackish hues.

Thus, answering is bird poop black requires acknowledging that while pure black droppings are uncommon in healthy birds, temporary darkening due to diet is normal and expected.

Environmental and Health Factors

Beyond diet, several environmental and physiological factors influence the appearance of bird droppings. Urban pollution, for instance, can lead birds to ingest particulate matter that alters stool color. Similarly, exposure to moldy grains or contaminated water sources may affect liver function, potentially resulting in abnormally colored excrement.

From a health perspective, persistent black droppings in pet birds should be evaluated by an avian veterinarian. Melena—black, tarry stools caused by digested blood—indicates possible gastric ulcers, infections, or toxicity. In wild birds, observing multiple individuals with similar abnormal droppings in one area might suggest localized contamination or disease outbreaks.

Conversely, dehydration can concentrate uric acid and fecal matter, making droppings appear darker than usual without indicating illness. Seasonal changes in hydration levels, especially during hot summers, may temporarily alter dropping appearance.

Cultural and Symbolic Interpretations of Bird Poop

Interestingly, across various cultures, bird droppings carry symbolic meanings—some superstitious, others humorous. In many European traditions, being hit by bird poop is considered a sign of good luck, possibly because such events are rare and unexpected, much like windfalls. In Russian folklore, it's said that if a bird poops on you, wealth is coming your way. Meanwhile, Turkish superstition interprets it as a sign of impending financial gain.

These beliefs likely stem from the idea that something unpleasant turning into fortune represents irony or divine favor. While there's no scientific basis for these claims, the cultural fascination underscores how even mundane biological phenomena like bird excrement capture human imagination. And given that darker droppings are more visible—especially on light surfaces—they may be disproportionately associated with these omens.

In modern urban settings, where pigeons and seagulls are common, complaints about bird droppings often focus on hygiene and property damage. Yet, few people stop to consider what the color reveals about the birds themselves. Understanding that bird poop isn't naturally black but can become so due to diet helps shift perception from mere nuisance to ecological indicator.

Practical Implications for Birdwatchers and Pet Owners

For birdwatchers and ornithologists, analyzing droppings—known as spoor—can provide valuable insights into species presence, feeding habits, and health status. When tracking elusive birds in the field, examining fresh droppings near roosting or nesting sites can help identify species based on size, shape, and color.

Here are practical tips for interpreting bird droppings:

- Check the context: Look at nearby food sources. Are berry-producing plants abundant? That could explain dark droppings.

- Assess consistency: Healthy droppings should have a distinct white cap (urates) and a separate fecal portion. Blended or slimy textures may indicate illness.

- Monitor changes over time: A single black dropping may be dietary; repeated observations suggest either consistent diet or potential health concern.

- Avoid direct contact: Bird droppings can carry pathogens like Chlamydia psittaci (psittacosis) or Salmonella. Always wear gloves when handling samples and wash hands thoroughly afterward.

Pet bird owners should establish a baseline for their bird’s normal droppings. Sudden shifts in color—especially toward black or red—should prompt immediate consultation with a vet. Keeping a photo log can aid diagnosis.

Regional Variations and Urban Observations

In cities worldwide, residents frequently report seeing black-stained surfaces beneath roosting birds. In coastal areas, gulls feeding on fish offal may produce slightly darker droppings. In agricultural zones, granivorous birds dominate, yielding greener waste. Tropical regions with fruit-heavy avian diets see more instances of near-black excrement.

Urban environments amplify visibility due to concrete, vehicles, and light-colored architecture. Pigeons in city centers, often fed bread and processed snacks by humans, may exhibit altered gut flora and irregular dropping colors—including darker shades. Some researchers suggest that artificial food coloring in junk food contributes to atypical pigmentation in urban bird populations.

| Bird Type | Typical Diet | Fecal Color | Urate (White) Color | Notes on Black Appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pigeon | Seeds, bread, scraps | Green-brown | White | Rarely black; dark if eating dyed foods |

| European Starling | Insects, berries, garbage | Variable, often dark | White | Fruit consumption can cause near-black droppings |

| American Robin | Worms, berries | Dark green to blackish | White | Frequent mulberry eaters leave black stains |

| Herring Gull | Fish, refuse | Tan to brown | White | Unlikely to appear black |

| Crow | Omnivorous | Dark brown | White | May look black under shadow or poor light |

Common Misconceptions About Bird Poop

Several myths persist about bird droppings, especially regarding color. One widespread belief is that all bird poop starts white and turns black over time. While oxidation can slightly darken uric acid, true blackening usually indicates either diet or decomposition.

Another misconception is that larger birds produce blacker droppings. Size affects volume, not inherent color. A bald eagle’s dropping is not inherently darker than a robin’s—it depends on what was consumed.

Lastly, some assume that black bird poop is always dangerous. While caution is wise, most dark droppings are harmless and diet-related. Pathogen risk exists regardless of color, so proper hygiene should always be practiced.

FAQs About Bird Poop Color

- Can bird poop be black?

- Yes, bird poop can appear black, especially after consuming dark fruits like mulberries or if affected by certain health conditions such as internal bleeding.

- Why does my bird’s poop look black?

- Black droppings in pet birds may result from diet (e.g., blueberries, iron supplements) or could indicate melena—a medical emergency requiring veterinary care.

- Is black bird poop dangerous?

- The color itself isn’t dangerous, but it can signal underlying health issues. Additionally, all bird droppings should be handled carefully due to potential pathogens.

- Do certain birds have black poop?

- No bird species naturally produces solid black poop, but frugivorous birds like robins and waxwings often have very dark droppings after eating pigmented fruits.

- How can I tell if black bird poop is normal?

- Consider recent diet, consistency, and frequency. If black droppings persist beyond a day or two in pets, consult a vet. In wild birds, occasional darkness after fruit season is normal.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4