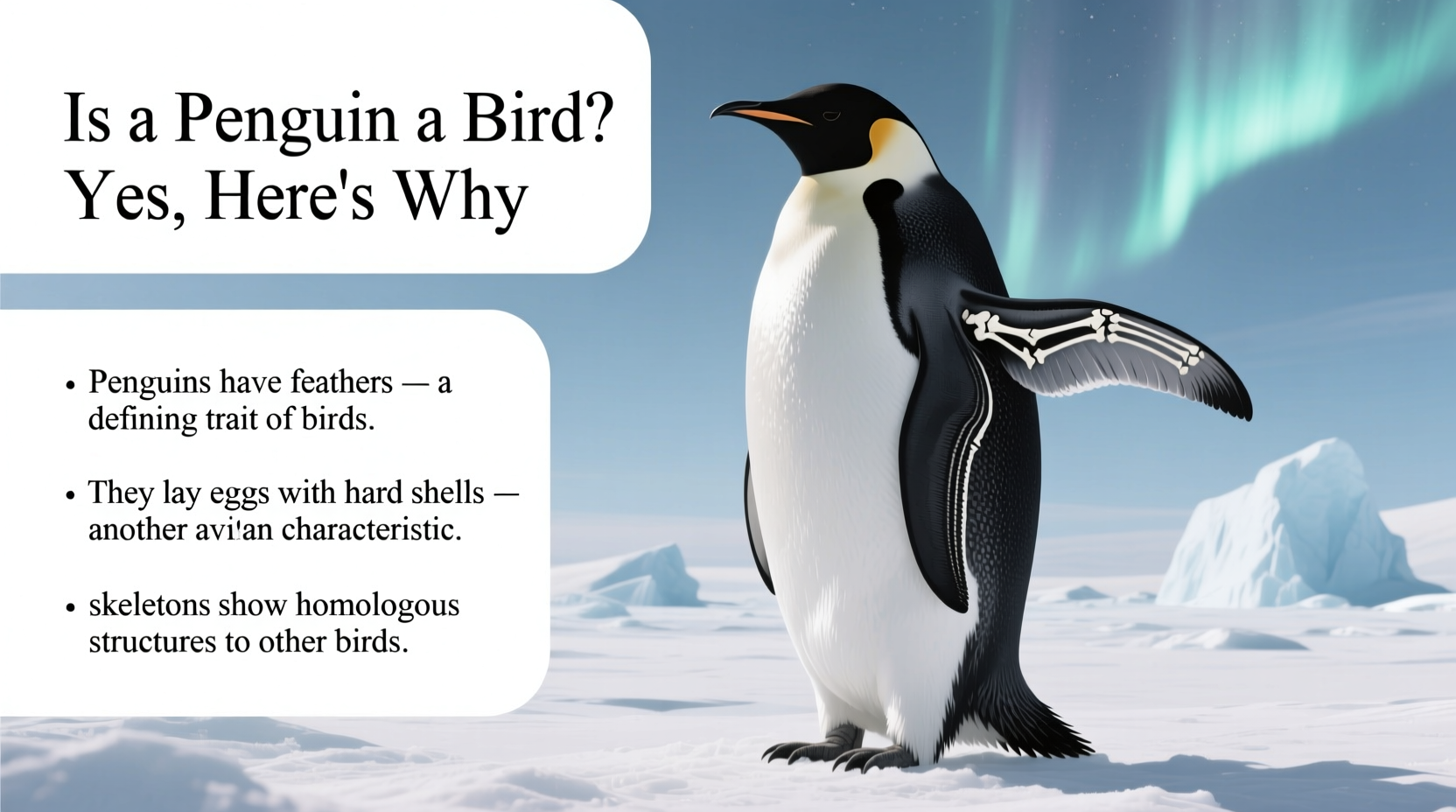

Yes, a penguin is a bird. This may surprise some people who associate birds primarily with flight, but the scientific classification confirms that penguins belong to the class Aves—the group that includes all birds. While they cannot fly in the air, penguins are expert swimmers and divers, using their wing-like flippers to 'fly' through water. The question is a penguin a bird often arises due to their unique appearance and lifestyle, but from a biological standpoint, penguins share all the defining characteristics of avian species: they have feathers, lay hard-shelled eggs, possess beaks, and are endothermic (warm-blooded). Understanding this helps clarify common misconceptions about what it truly means to be a bird.

Defining What Makes a Bird a Bird

To fully appreciate why penguins are classified as birds, it’s essential to understand the biological criteria used by ornithologists. Birds are members of the phylum Chordata and class Aves, distinguished by several key features:

- Feathers: No other animal group has true feathers. Even flightless birds like ostriches, emus, and penguins are covered in feathers, which serve insulation, waterproofing, and sometimes display purposes.

- Beaks or Bills: Birds lack teeth and instead have beaks made of keratin, adapted for various diets and ecological roles.

- Laying Hard-Shelled Eggs: All birds reproduce by laying amniotic eggs with calcified shells, protecting the developing embryo.

- High Metabolic Rate and Warm-Bloodedness: Birds maintain a constant internal body temperature, allowing them to remain active in diverse environments.

- Skeletal Adaptations: Hollow bones reduce weight for flight in most species, though in penguins, these bones are denser to aid diving.

Penguins meet every one of these criteria. Their wings have evolved into flippers suited for aquatic propulsion rather than aerial flight, but structurally, they retain the same bone layout as flying birds. This evolutionary adaptation does not exclude them from the bird category—it highlights how versatile avian evolution can be.

Evolutionary History of Penguins

Penguins evolved around 60 million years ago, shortly after the extinction of the dinosaurs. Fossil evidence suggests that early penguin ancestors were capable of flight and gradually adapted to marine life over millions of years. Over time, natural selection favored individuals with stronger swimming abilities, leading to shorter wings, heavier bodies, and enhanced oxygen storage—all beneficial for deep diving.

The oldest known penguin fossil, Waimanu manneringi, dates back to the Paleocene epoch in New Zealand. These ancient penguins resembled modern ones in body shape but retained some primitive features. Today, there are approximately 18 recognized penguin species, ranging from the tiny blue penguin (Eudyptula minor) of Australia and New Zealand to the towering emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) of Antarctica.

Where Do Penguins Live? Geographic Distribution

Contrary to popular belief, not all penguins live in Antarctica. While iconic species like the emperor and Adélie penguins inhabit the icy southern continent, others thrive in temperate and even subtropical regions:

- Antarctica & Subantarctic Islands: Home to emperor, Adélie, chinstrap, and gentoo penguins.

- South America: Magellanic and Humboldt penguins breed along the coasts of Chile, Argentina, and Peru.

- Australia and New Zealand: Little blue penguins and yellow-eyed penguins nest in coastal areas.

- Galápagos Islands: The Galápagos penguin is the only species found north of the equator, surviving thanks to cold ocean currents.

This wide distribution underscores the adaptability of penguins across different climates, further proving their success as a bird lineage despite flightlessness.

Flightless But Not Defenseless: How Penguins Survive

Flightlessness in birds typically evolves on islands without land predators. For penguins, losing the ability to fly was a trade-off for superior underwater agility. In water, penguins can reach speeds up to 22 mph (35 km/h), outmaneuvering seals and orcas with quick turns and bursts of speed.

On land, however, penguins face challenges. Their upright posture and waddling gait make them slow and vulnerable. To compensate, many species form large colonies for protection, rely on camouflage (countershading—dark backs and light bellies), and choose remote nesting sites inaccessible to most predators.

Emperor penguins take survival to an extreme, breeding during the harsh Antarctic winter. Males incubate eggs on their feet under a brood pouch while enduring temperatures below -40°C and winds exceeding 100 mph. This remarkable behavior showcases the physiological and behavioral adaptations that define avian resilience.

Biology and Physiology of Penguins

Beneath their tuxedo-like plumage lies a suite of specialized adaptations:

- Countercurrent Heat Exchange: Blood vessels in their legs and flippers minimize heat loss by warming returning cold blood with outgoing warm blood.

- Dense Feathers: Up to 100 feathers per square inch create a waterproof barrier, essential for staying dry and insulated in frigid waters.

- Oxygen Efficiency: Penguins can slow their heart rate and redirect blood flow during dives, allowing some species to stay submerged for over 20 minutes and dive deeper than 500 meters.

- Salt Glands: Located near the eyes, these glands excrete excess salt ingested from seawater, enabling long-term marine living.

These traits reflect advanced avian biology, demonstrating that flight is just one of many survival strategies within the bird class.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Penguins

Beyond science, penguins hold symbolic meaning in human culture. Often associated with loyalty, perseverance, and community, they appear frequently in literature, film, and branding. Their monogamous mating habits and cooperative parenting resonate with themes of family and dedication.

In environmental movements, penguins serve as flagship species for climate change awareness. Images of emaciated emperor penguins or melting ice shelves evoke public concern about polar ecosystems. Conservation campaigns often ask, is a penguin a bird worthy of protection?—highlighting both biological truth and ethical responsibility.

Indigenous cultures in the Southern Hemisphere, such as the Yaghan people of Tierra del Fuego, have oral traditions referencing penguins, viewing them as curious sea creatures with human-like behaviors. Modern symbolism continues this reverence, portraying penguins as resilient survivors in extreme conditions.

Common Misconceptions About Penguins

Despite widespread fascination, several myths persist:

- Misconception 1: Penguins are mammals because they don’t fly.

Reality: Flightlessness doesn’t disqualify an animal from being a bird. Ostriches, kiwis, and cassowaries also cannot fly but are definitively birds. - Misconception 2: All penguins live in snow.

Reality: Only a few species inhabit Antarctica. Many live in mild or warm climates. - Misconception 3: Penguins mate for life.

Reality: While many pairs reunite annually, divorce rates vary by species. Some, like Adélies, show high partner fidelity; others switch mates more frequently. - Misconception 4: Penguins are fish.

Reality: Though they eat fish and swim like them, penguins are warm-blooded, air-breathing vertebrates with feathers—hallmarks of birds.

Clarifying these misunderstandings reinforces accurate biological knowledge and enhances public appreciation of avian diversity.

How to Observe Penguins: Tips for Birdwatchers

For bird enthusiasts wondering is a penguin a bird worth seeing in the wild, the answer is a resounding yes. Observing penguins offers a unique glimpse into avian adaptation. Here are practical tips for responsible penguin watching:

- Choose Ethical Tour Operators: Select eco-certified guides who follow wildlife disturbance guidelines (e.g., maintaining 5-meter distance).

- Visit During Breeding Season: Timing your trip to coincide with nesting increases chances of witnessing courtship, chick-rearing, and colony dynamics.

- Respect Local Regulations: Many penguin habitats are protected. Follow marked paths and avoid flash photography.

- Use Binoculars or Telephoto Lenses: Get close-up views without encroaching on sensitive areas.

- Support Conservation Efforts: Donate to organizations like the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition or attend educational programs at accredited zoos.

Popular locations include South Georgia Island (king penguin rookeries), the Falkland Islands (multiple species), and Phillip Island in Australia (famous for nightly little penguin parades).

Threats Facing Penguins Today

Unfortunately, nearly half of all penguin species are threatened or near-threatened due to:

- Climate Change: Melting sea ice reduces habitat for ice-dependent species like emperors and affects krill populations, a key food source.

- Overfishing: Depletes fish stocks that penguins rely on, forcing longer foraging trips and lower chick survival.

- Oil Spills: Coat feathers, destroying insulation and buoyancy, often leading to hypothermia and death.

- Invasive Species: Rats, cats, and dogs introduced to islands prey on eggs and chicks.

Conservationists use satellite tracking, population monitoring, and marine protected areas to safeguard penguin colonies. Public awareness—sparked by questions like is a penguin a bird—plays a vital role in driving policy changes and funding research.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can penguins fly?

No, penguins cannot fly in the air. Their wings have evolved into flippers for swimming. However, they are exceptionally agile underwater, 'flying' through water with powerful strokes.

Are penguins related to dinosaurs?

Yes. Like all birds, penguins are descendants of theropod dinosaurs. They share a common ancestor with species like Velociraptor, making them living dinosaurs in evolutionary terms.

Do penguins have knees?

Yes, penguins have knees hidden beneath their feathers and skin. Their leg structure includes femur, kneecap, tibia, and fibula, folded to give them their characteristic waddle.

Why do penguins look like they’re wearing suits?

Their black-and-white coloration provides countershading camouflage. From above, their dark backs blend with deep water; from below, their white bellies match the sky.

How long do penguins live?

Lifespan varies by species. Emperor penguins can live over 20 years in the wild, while smaller species like the little penguin average 6–10 years.

In conclusion, the answer to is a penguin a bird is unequivocally yes. Penguins embody the incredible diversity and adaptability of the avian world. Whether gliding through Antarctic waters or marching across ice fields, they remain feathered, egg-laying, warm-blooded members of the bird family tree. Recognizing this fact enriches our understanding of evolution, ecology, and the interconnectedness of life on Earth.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4