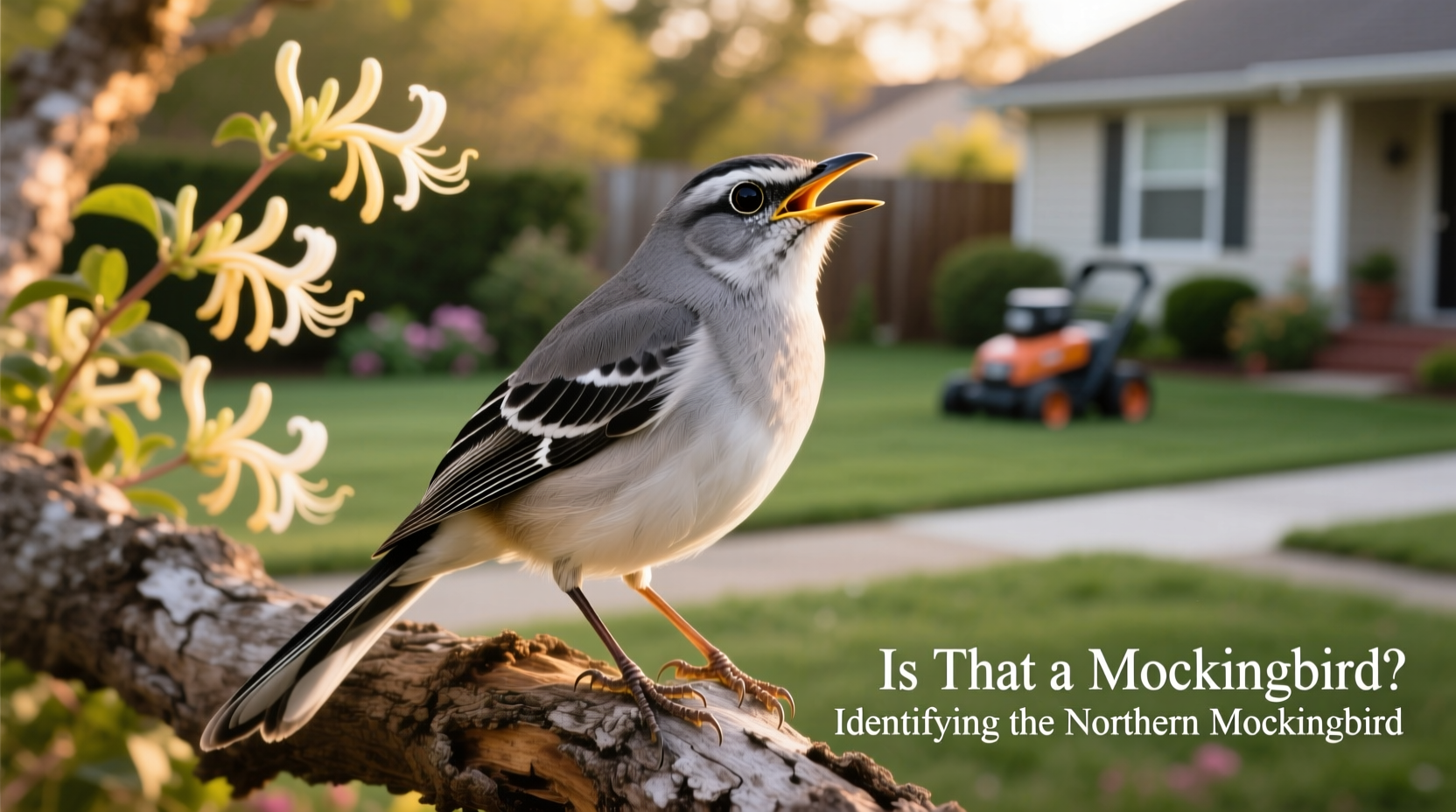

Yes, that could very well be a mockingbird—specifically, the Northern Mockingbird (*Mimus polyglottos*)—if you’re seeing a medium-sized gray-and-white bird boldly perched on a rooftop, fencepost, or tree, singing a complex series of repeated phrases at all hours of the day (and sometimes night). One of the most frequently asked questions among backyard birdwatchers is is that a mocking bird, especially in suburban areas across North America where this clever mimic thrives. The answer often lies in a combination of physical traits, vocal behavior, and territorial habits unique to this species.

What Makes the Northern Mockingbird Unique?

The Northern Mockingbird is not just another songbird—it’s a master performer, cultural symbol, and ecological survivor. Found year-round throughout much of the United States, especially in the southern and central regions, this bird stands out for its remarkable ability to imitate the calls of other birds, animals, and even mechanical sounds like car alarms. This talent gives rise to frequent searches such as how to tell if that bird is a mockingbird or why does that bird sound like multiple different birds.

Scientifically classified under the family Mimidae (which includes thrashers and catbirds), the mockingbird earns its name from its mimicking prowess. Unlike many birds that sing simple melodies, the mockingbird delivers long sequences of musical notes, each phrase repeated two to six times before switching to a new one. These performances can go on for hours, particularly during breeding season when males are trying to attract mates or defend territory.

Physical Identification: How to Confirm It’s a Mockingbird

If you're wondering is that a mocking bird, start by observing its physical characteristics:

- Size and Shape: About 8–10 inches long with a slender body, long tail, and short, rounded wings. Its silhouette is often upright and alert.

- Coloration: Pale gray upperparts, whitish underparts, and distinctive white wing patches visible in flight. When it spreads its wings during display flights, these bright white flashes are unmistakable.

- Bill: Thin, straight, and black, slightly curved downward—ideal for probing lawns for insects.

- Eyes: Dark and prominent, giving it an intense, watchful expression.

- Tail: Long and often moves up and down while walking on the ground.

One common confusion arises between mockingbirds and similar-looking species such as the Gray Catbird or the Shama Thrush (in non-native regions). However, the catbird lacks the white wing patches and has a slimmer tail, while the shama—though also a strong mimic—is more colorful and typically found only in captivity or tropical zones outside the U.S.

Vocal Behavior: The Key Clue in Answering 'Is That a Mocking Bird?'

Vocalization is perhaps the strongest indicator. If the bird you heard repeated a phrase—like a robin's call, then a cardinal's whistle, then a jay's screech, then back to the robin again—it’s highly likely you’ve encountered a mockingbird. They don’t just copy once; they repeat each sound multiple times in succession.

This repetition pattern distinguishes them from other mimics. For example, the Brown Thrasher has a vast repertoire but usually repeats each phrase only twice, while the mockingbird repeats three, four, or more times. Nighttime singing is also common, especially among unpaired males in spring and early summer, leading some people to wonder why is there a bird singing at 3 a.m.?—a question often linked to mockingbirds in urban environments.

| Feature | Mockingbird | Gray Catbird | Brown Thrasher |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wing Patches | White, very visible | None | Faint reddish-brown streaks |

| Vocal Repetition | 3–6 times per phrase | Irregular, no repetition | Typically twice |

| Nesting Habitat | Open areas, shrubs, human structures | Dense thickets | Brushy fields | Nocturnal Singing | Common (males) | Rare | Rare |

Habitat and Range: Where You Might See a Mockingbird

The Northern Mockingbird is a permanent resident across most of the southern and central United States, ranging from the Atlantic coast to the Pacific, and northward into parts of Oregon, Idaho, and New England. It’s the state bird of five U.S. states: Florida, Mississippi, Tennessee, Texas, and Arkansas—more than any other bird—highlighting its cultural significance.

They thrive in open habitats with scattered trees and shrubs, including:

- Suburban lawns and gardens

- Parks and golf courses

- Agricultural edges

- Urban parking lots and rooftops

Unlike many wild birds, mockingbirds have adapted exceptionally well to human development. Their presence near homes increases the likelihood of someone asking, is that a mocking bird I hear outside my window at midnight? Yes—it might be, especially during mating season (March through July).

Cultural Symbolism of the Mockingbird

Beyond biology, the mockingbird holds deep symbolic meaning in American culture. Most famously, Harper Lee’s novel To Kill a Mockingbird uses the bird as a metaphor for innocence and moral integrity. In the story, harming a mockingbird is considered a sin because it “doesn’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy.” This literary reference has cemented the bird’s image as a gentle, beneficial creature—one that should be protected rather than disturbed.

In folklore, the mockingbird is seen as a messenger, a guardian, and a symbol of awareness due to its constant vigilance and vocal communication. Some Native American traditions view it as a teacher of songs and stories. Meanwhile, in modern pop culture, the name appears in music (e.g., Taylor Swift’s “Mockingbird”), films, and even cybersecurity (“mockingbird attacks” refer to AI-generated voice impersonations—a nod to the bird’s deceptive mimicry).

Behavioral Traits: Territoriality and Diet

Despite their melodic reputation, mockingbirds can be fiercely aggressive when defending nests or food sources. They are known to dive-bomb cats, dogs, squirrels, and even humans who get too close to their young. This boldness makes them easy to spot—but also occasionally unwelcome in residential areas.

During nesting season (typically April to August), a single pair may raise two or three broods. Nests are built in shrubs or small trees, often thorny ones like hawthorn or multiflora rose, which offer protection. Both parents feed the chicks, primarily with insects early in the season and shifting to berries and fruits later in the year.

Diet-wise, mockingbirds are omnivorous:

- Spring/Summer: Insects (beetles, grasshoppers, wasps, ants), spiders, earthworms

- Fall/Winter: Berries from plants like pokeweed, sumac, holly, and pyracantha

Gardeners can attract mockingbirds by planting native berry-producing shrubs and avoiding pesticide use, which reduces insect availability.

Myths and Misconceptions About Mockingbirds

Several myths persist about this bird, often influencing whether people welcome them into their yards:

- Myth: Mockingbirds mimic only birds.

Truth: They imitate frogs, crickets, dogs, sirens, and even cell phone ringtones. - Myth: Hearing a mockingbird sing at night means bad luck.

Truth: It’s simply an unpaired male trying to attract a mate; no supernatural meaning exists. - Myth: All grayish songbirds are mockingbirds.

Truth: Many species look similar; proper ID requires attention to wing patterns and vocal behavior. - Myth: Mockingbirds harm other birds.

Truth: While territorial, they rarely kill or eat other birds. Their aggression is defensive, not predatory.

How to Observe and Support Mockingbirds Ethically

If you suspect is that a mocking bird in your yard, here are practical tips for observation and coexistence:

- Use binoculars: Get a clear view without approaching the nest.

- Listen carefully: Record or note repeated phrases in its song.

- Avoid nest disturbance: Federal law protects native birds under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act—never touch eggs or nests.

- Provide habitat: Plant dense shrubs and native fruit-bearing trees.

- Limit outdoor cats: Free-roaming cats are a leading cause of nest failure.

For serious birders, keeping a journal of vocalizations or using apps like Merlin Bird ID or Audubon Bird Guide can help confirm sightings. Uploading audio recordings to platforms like eBird or xeno-canto allows experts to verify identifications and contribute to citizen science.

Regional Differences in Mockingbird Populations

While widespread, mockingbird density varies by region. They are most abundant in the Southeast and Southwest U.S., where mild winters and open landscapes favor their survival. In northern areas like Michigan or New York, populations may fluctuate depending on winter severity.

Interestingly, urban mockingbirds tend to sing more complex songs and at higher pitches to overcome background noise—a phenomenon studied in cities like Phoenix and Houston. Rural individuals may have broader repertoires drawn from natural soundscapes, whereas city dwellers incorporate artificial sounds more frequently.

Final Thoughts: Confirming 'Is That a Mocking Bird'

So, is that a mockingbird? Look for the white wing patches in flight, listen for repeated phrases in the song, and observe bold daytime behavior—even chasing off crows or hawks many times their size. Combine visual, auditory, and behavioral clues to make a confident identification.

Whether admired for its song, respected for its courage, or studied for its intelligence, the Northern Mockingbird remains one of North America’s most fascinating avian residents. Next time you hear a bird singing late at night or mimicking half a dozen others in your backyard, take a closer look—you might just be sharing your space with a true feathered virtuoso.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why is a bird singing at night in my backyard?

A: It’s likely a male Northern Mockingbird, especially during breeding season. Unpaired males often sing at night to attract mates.

Q: Do mockingbirds migrate?

A: Most Northern Mockingbirds are non-migratory and stay in their range year-round, though northernmost populations may move south in harsh winters.

Q: Are mockingbirds protected by law?

A: Yes. Under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, it’s illegal to harm, capture, or possess mockingbirds, their eggs, or nests without a permit.

Q: How can I stop a mockingbird from attacking me near my house?

A: It’s likely guarding a nearby nest. Avoid the area if possible, wear a hat, or hang reflective tape to deter dive-bombing. Behavior usually stops after fledging (3–4 weeks).

Q: Can female mockingbirds sing?

A: Yes, though less frequently than males. Females sing primarily during nest defense and in winter, and their songs are generally shorter and less varied.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4