The parts of a bird’s lower limbs are not simply called ‘legs’ in the same way as in mammals; instead, what we commonly refer to as a bird’s leg involves a specialized anatomical structure with unique terminology. So, what are bird legs called? The visible portion below the body, often mistaken for the entire leg, is primarily the tarsometatarsus and the digits, while the true upper leg (femur) is usually hidden beneath feathers. This distinction is key when studying avian anatomy, understanding bird locomotion, or identifying species during birdwatching. A natural long-tail keyword variant such as ‘what are bird legs called and their scientific names’ reflects the depth of inquiry behind this seemingly simple question, combining biological accuracy with practical ornithological interest.

Anatomical Breakdown: What Are Bird Legs Made Of?

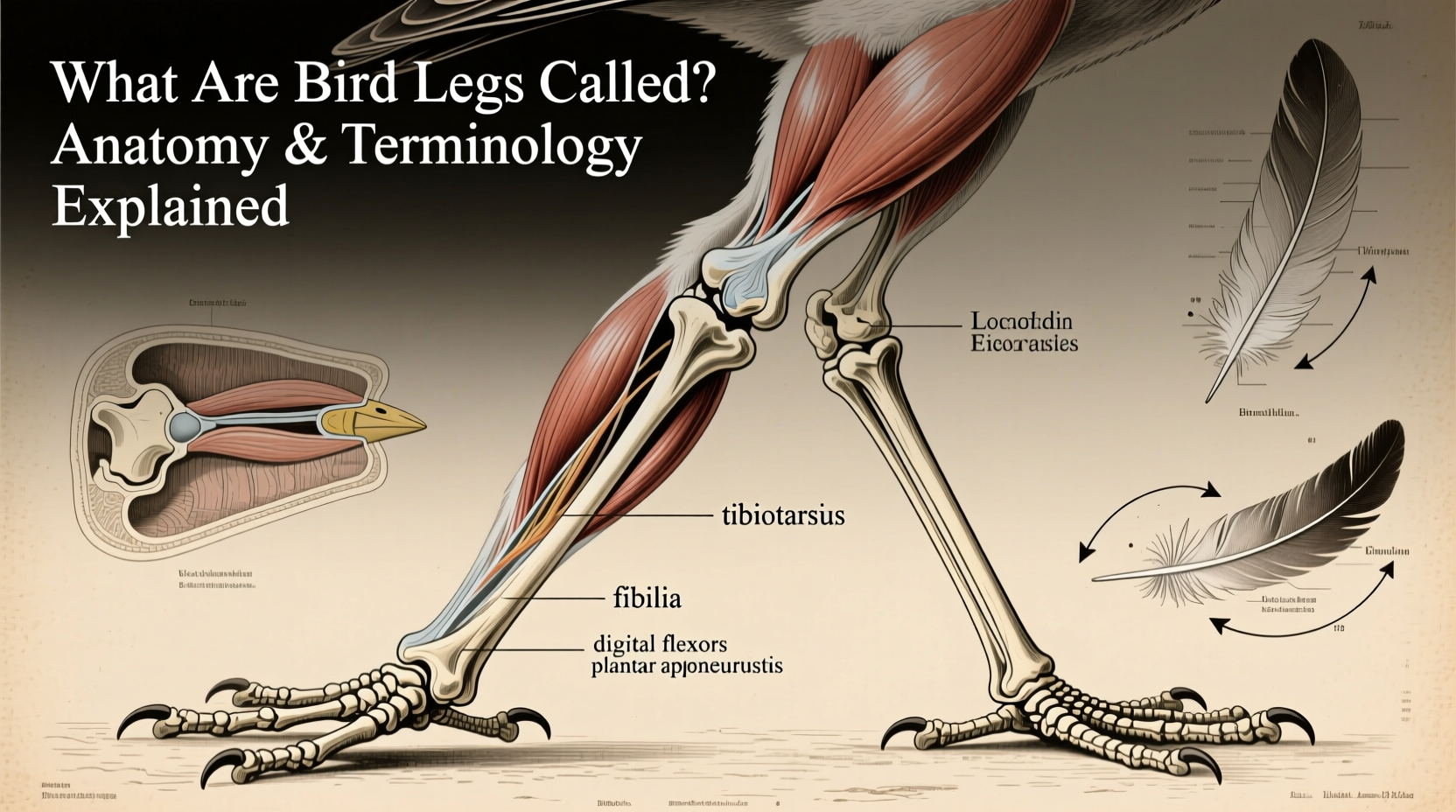

To fully understand what bird legs are called, it's essential to explore the actual skeletal and muscular components that make up the avian lower limb. Unlike humans, birds have a highly modified leg structure adapted for flight, perching, swimming, or running, depending on the species. The avian leg consists of several distinct segments:

- Femur: The uppermost bone of the leg, equivalent to the human thigh bone. It is short and mostly concealed within the bird’s body by muscle and feathers.

- Tibiotarsus: Formed by the fusion of the tibia and proximal tarsal bones, this long bone runs from the knee joint down to the ankle.

- Tarsometatarsus: A fused structure combining the distal tarsals and metatarsals, forming the main weight-bearing segment visible in most standing birds.

- Digits (toes): Usually three or four forward-pointing toes, sometimes with a hallux (reversed first toe), used for gripping, scratching, or swimming.

The joint that appears to be the ‘knee’ in birds actually corresponds to our ankle, not the knee. The real knee is located higher up, near the body, and is rarely visible. This common misconception leads many people to ask, ‘why do bird legs bend backwards?’—they don’t. They bend forward, just like ours; it’s the elongated tarsometatarsus that gives the illusion of reverse articulation.

Why Is Avian Leg Structure Important for Survival?

Bird leg anatomy is directly tied to ecological adaptation. The structure, length, and shape of a bird’s legs determine its habitat, feeding behavior, and mode of locomotion. For example:

- Wading birds like herons and flamingos have extremely long legs and tarsometatarsi, allowing them to walk through shallow water without submerging their bodies.

- Perching birds (passerines) possess a specialized tendon-locking mechanism in their legs that automatically tightens their grip on branches when they squat, enabling them to sleep without falling.

- Raptors such as eagles and owls have powerful legs and talons designed for capturing and killing prey.

- Aquatic birds like ducks and grebes have webbed feet connected by skin between the toes, enhancing swimming efficiency.

- Running birds such as ostriches have strong, elongated tarsometatarsi that function like spring-loaded limbs, contributing to high-speed terrestrial movement.

Understanding what bird legs are called helps researchers and birdwatchers interpret these adaptations. Terms like ‘anisodactyl foot’ (three toes forward, one back) or ‘zygodactyl arrangement’ (two toes forward, two backward) are part of the precise vocabulary used in ornithology to describe functional morphology.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Bird Legs

Beyond biology, bird legs carry symbolic meaning across cultures. In many indigenous traditions, the strength and agility of bird legs represent freedom, spiritual ascent, and connection between earth and sky. For instance:

- In Native American symbolism, the eagle’s powerful legs and talons signify authority, courage, and divine protection.

- In ancient Egyptian art, birds like the ibis were depicted with long, slender legs symbolizing wisdom and balance.

- In some African folklore, the stilt-legged crane is associated with patience and vigilance due to its slow, deliberate movements in wetlands.

Even in modern language, idioms such as ‘on skinny bird legs’ imply fragility or instability, reflecting how physical traits influence metaphorical expression. Knowing the correct terminology—such as tarsus or hallux”>—adds precision when discussing these cultural depictions in academic or artistic contexts.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Legs

One of the most widespread misunderstandings is the belief that birds have knees that bend backward. As previously explained, this is false. The joint that bends in the middle of the leg is analogous to the human ankle, not the knee. Another misconception is that all birds have similar leg structures. In reality, leg proportions vary dramatically:

| Bird Type | Leg Length | Toe Arrangement | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ostrich | Very long | Two toes (didactyl) | Running at high speed |

| Sparrow | Short | Anisodactyl (3 forward, 1 back) | Perching and hopping |

| Pelican | Moderate, webbed | Pamprodactyl (all four toes connected) | Swimming |

| Woodpecker | Short, strong | Zygodactyl (2 forward, 2 back) | Climbing tree trunks |

| Heron | Extremely long | Anisodactyl with long toes | Wading in shallow water |

These differences underscore why generalizations about bird legs can be misleading. Using accurate terminology like ‘tarsometatarsus’ instead of vague references to ‘the lower leg’ improves both scientific communication and public understanding.

Practical Tips for Observing Bird Legs While Birdwatching

For amateur and experienced birders alike, paying attention to leg characteristics can aid in species identification. Here are actionable tips:

- Note leg color: Many birds, such as the Black-winged Stilt or Yellow-legged Gull, have brightly colored legs that serve as key field marks.

- Observe posture and stance: Does the bird stand upright (like a crane) or crouch low (like a rail)? Posture reveals clues about skeletal structure and habitat preference.

- Watch foot usage: See if the bird uses its feet for grasping (raptors), scratching (chickens), swimming (ducks), or climbing (woodpeckers).

- Use binoculars or a spotting scope: Focus on the junction between the body and leg to estimate where the femur ends and the tibiotarsus begins.

- Consult field guides with anatomical diagrams: Some advanced guides include labeled illustrations showing what bird legs are called and how they differ among families.

When documenting sightings, consider recording leg-related features alongside plumage and call notes. Over time, this builds a more comprehensive understanding of avian diversity.

How Scientists Study Bird Leg Anatomy

Ornithologists use various methods to examine bird legs, ranging from dissection to digital imaging. X-rays and CT scans allow non-invasive study of bone structure, particularly useful in paleornithology (the study of fossil birds). Comparative anatomy helps trace evolutionary relationships; for example, the similarity between dinosaur leg bones and those of modern birds supports the theory that birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs.

Muscle fiber analysis reveals how different species generate power for takeoff, landing, or sustained perching. Biomechanical studies measure forces exerted by legs during walking, jumping, or landing, providing insights into energy efficiency and injury prevention in captive birds.

Researchers also investigate developmental biology—how leg structures form in embryos. This knowledge aids conservation efforts, especially for endangered species where limb deformities may indicate environmental toxins or genetic bottlenecks.

Educational Value: Teaching Kids and Students About Bird Legs

Introducing students to the question ‘what are bird legs called?’ opens doors to broader lessons in biology, evolution, and ecology. Teachers can design engaging activities such as:

- Comparing chicken bones (from cooked meals) to diagrams of avian skeletons.

- Creating models using pipe cleaners and beads to simulate the tarsometatarsus and digits.

- Conducting backyard observations to classify local birds by leg type and infer lifestyle.

- Discussing how adaptations like webbed feet or zygodactyl toes solve survival challenges.

Using precise terminology early on fosters scientific literacy. Instead of saying ‘bird feet,’ encourage learners to say ‘digits’ or ‘tarsi’ when appropriate. Questions like ‘why do ducks have webbed feet?’ naturally lead to deeper exploration of form and function.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What are the parts of a bird’s leg called?

- The main parts are the femur (hidden), tibiotarsus, tarsometatarsus, and digits (toes). The tarsometatarsus is the long, visible segment often mistaken for the entire leg.

- Do birds have knees?

- Yes, birds have knees, but they are located high up near the body and are usually covered by feathers. The joint that looks like a backward-bending knee is actually the ankle (intertarsal joint).

- Why do bird legs look like they bend backwards?

- They don’t bend backward. The apparent ‘reverse knee’ is the ankle joint. The elongated tarsometatarsus extends downward, creating the illusion of reversed articulation.

- Can you tell a bird’s lifestyle from its legs?

- Absolutely. Long legs suggest wading, webbed feet indicate swimming, strong talons point to predation, and short, sturdy legs are typical of ground-dwelling or perching birds.

- Are bird legs homologous to human legs?

- Yes, bird and human legs are homologous structures, meaning they share a common evolutionary origin. However, bird legs are highly modified for bipedal locomotion and flight-related adaptations.

In conclusion, understanding what bird legs are called goes far beyond memorizing anatomical terms. It connects biology with behavior, culture, and observation. Whether you're a student, educator, researcher, or casual bird enthusiast, recognizing the complexity behind avian leg structure enriches your appreciation of nature’s engineering. By learning terms like tarsometatarsus and hallux, and observing how different species use their legs, you gain deeper insight into the remarkable diversity of birds across the globe.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4