The phrase 'what are the birds in flow' does not refer to a scientifically recognized ornithological phenomenon, but rather appears to be a poetic or metaphorical expression that may stem from interpretations of birds moving together in harmonious patterns—such as flocks flowing across the sky during migration or murmurations. Birds in flow typically describe species like starlings, sandpipers, or geese that exhibit coordinated group flight behavior, where individuals move in unison, creating mesmerizing aerial displays. This natural spectacle, often called 'bird flow' or 'avian flow dynamics,' combines biology, physics, and emergent behavior, making it a compelling subject for both birdwatchers and cultural scholars alike.

Understanding the Concept of 'Birds in Flow'

When people ask 'what are the birds in flow,' they're often referring to the visual and behavioral phenomenon of birds flying in synchronized groups. These movements create fluid, wave-like patterns in the sky, resembling a living river of wings. The term isn't used in formal scientific literature, but it captures the essence of collective animal motion seen in species such as European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris), dunlins (Calidris alpina), and snow geese (Anser caerulescens). Such behaviors are most noticeable at dawn or dusk when large flocks gather near roosting or feeding sites.

This flowing motion emerges from simple rules followed by each individual bird: maintain proximity to neighbors, align direction with nearby birds, and avoid collisions. No single bird leads; instead, decisions ripple through the flock almost instantly, allowing the group to respond to predators or environmental changes with astonishing speed. Scientists study these patterns using computational models and high-speed cameras to understand how decentralized systems achieve complex coordination—a concept applicable to robotics, traffic systems, and even human crowd dynamics.

Biological Mechanisms Behind Coordinated Flight

The ability of birds to fly in cohesive, flowing formations is rooted in evolutionary adaptations that enhance survival. Flocking offers several key advantages:

- Predator avoidance: A swirling mass of birds confuses predators like hawks and falcons, making it difficult to target a single individual.

- Improved foraging efficiency: Information about food sources spreads rapidly through the flock via movement cues.

- Energy conservation: In V-formations (common among geese), birds take advantage of upwash from wingtips, reducing energy expenditure during long migrations.

Neurologically, birds possess highly developed visual processing centers that allow them to track multiple neighbors simultaneously. Their reaction times are incredibly fast—often under 100 milliseconds—which enables real-time adjustments in speed and direction without centralized control. Research conducted at the University of Oxford and the Max Planck Institute has shown that starling flocks behave like physical systems governed by principles similar to magnetism or fluid dynamics, where local interactions produce global order.

Species Known for 'Flowing' Behavior

While many bird species form flocks, only certain ones exhibit the dramatic, fluid-like movements associated with 'birds in flow.' Below are some of the most notable examples:

| Species | Common Name | Typical Habitat | Seasonality | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sturnus vulgaris | European Starling | Urban areas, farmlands, wetlands | Winter (murmurations) | Forms massive murmurations; iridescent plumage |

| Anser caerulescens | Snow Goose | Coastal marshes, agricultural fields | Fall and spring migration | Flies in tight V-formations; white morph dominates |

| Calidris alpina | Dunlin | Mudflats, estuaries | Year-round in temperate zones; migratory elsewhere | Highly synchronized shorebird flights |

| Corvus brachyrhynchos | American Crow | Woodlands, suburban areas | Year-round; increased movement in winter | Intelligent; forms large communal roosts |

| Rynchops nigra | Black Skimmer | Coastal lagoons, sandy beaches | Summer breeding season | Skims water surface; flies low in formation |

Each of these species demonstrates unique aspects of avian flow. For instance, starling murmurations can involve tens of thousands of birds and occur primarily in late autumn and winter, especially in the UK and parts of Italy. Dunlins, on the other hand, perform rapid, zigzagging maneuvers over tidal flats, responding to peregrine falcon attacks with split-second precision.

Cultural and Symbolic Interpretations of Bird Flow

Beyond their biological significance, flowing bird formations have inspired myths, art, and spiritual symbolism across cultures. In Native American traditions, flocks of birds moving as one are often interpreted as messages from the spirit world, symbolizing unity, transformation, and divine guidance. Similarly, in Celtic folklore, starling murmurations were believed to represent the souls of ancestors returning to earth.

In modern times, the image of birds in flow has become a powerful metaphor in psychology and organizational theory. Terms like 'swarm intelligence' and 'collective consciousness' borrow from avian flocking behavior to describe how decentralized groups—whether human teams or digital networks—can achieve coherence without top-down control. Poets and filmmakers frequently use footage of murmurations to evoke themes of freedom, resilience, and interconnectedness.

Artists such as Richard Shilling create land art using natural materials arranged in flowing patterns reminiscent of bird flocks, while choreographers have modeled dance routines on starling movements. This cross-disciplinary fascination underscores how deeply the phenomenon resonates with human imagination.

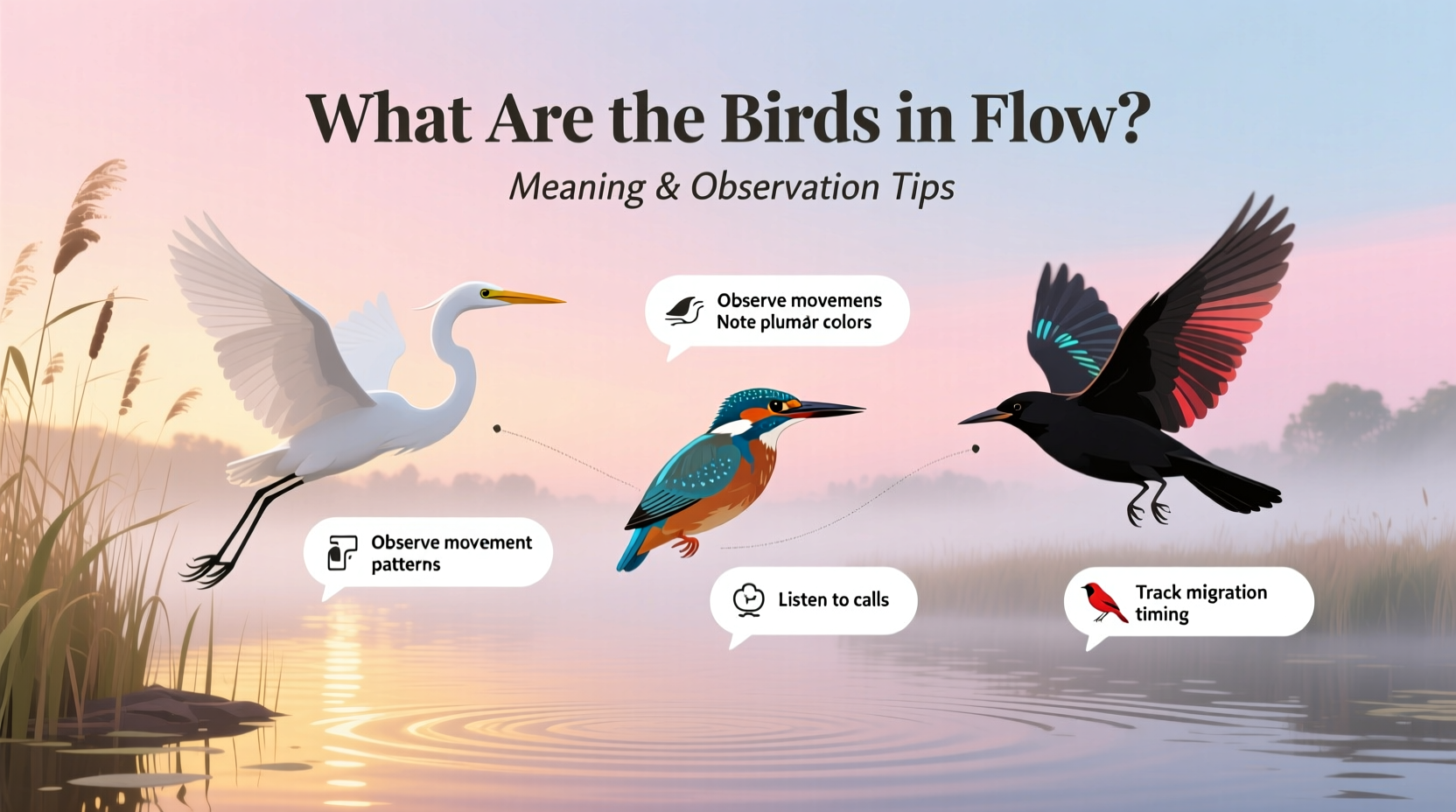

How to Observe Birds in Flow: A Practical Guide for Birdwatchers

If you're interested in witnessing birds in flow firsthand, timing, location, and preparation are crucial. Here’s how to maximize your chances:

- Choose the right season: Most flowing behaviors peak during migration periods (spring: March–May; fall: September–November) or winter roosting seasons (December–February).

- Visit known hotspots: Locations like Gretna Green in Scotland, the Somerset Levels in England, and the Bolinas Lagoon in California are famous for starling murmurations. Coastal estuaries such as Delaware Bay attract vast numbers of dunlins and sandpipers.

- Arrive early: Get to your observation site at least 30 minutes before sunset, as this is when flocks begin gathering for evening roosts.

- Use appropriate gear: Binoculars (8x42 or 10x42) help identify species, while a tripod-mounted camera with video capability allows you to capture the full scope of the display.

- Respect wildlife: Keep noise to a minimum, avoid sudden movements, and stay behind designated viewing areas to prevent disturbing the birds.

Local birdwatching clubs and Audubon Society chapters often organize guided events during peak seasons. Checking eBird.org for recent sightings can also help pinpoint active locations. Remember that weather conditions affect flocking behavior—overcast days tend to produce more dramatic displays than windy or rainy ones.

Common Misconceptions About Birds in Flow

Despite growing public interest, several misconceptions persist about birds in flow:

- Myth: One bird leads the flock.

Reality: There is no leader. Each bird responds to its immediate neighbors, resulting in self-organized patterns. - Myth: All flocks show flowing behavior.

Reality: Only certain species exhibit true fluid-like motion. Many flocks fly loosely without tight coordination. - Myth: Technology is needed to understand flocking.

Reality: While drones and AI aid research, basic principles can be observed with the naked eye and patience.

Another common confusion arises between migration routes and daily flocking behavior. While migrating birds may travel hundreds of miles in formation, 'birds in flow' usually refers to short-range, localized movements around roosts or feeding grounds, not transcontinental journeys.

Scientific Research and Technological Applications

The study of birds in flow extends beyond ecology into engineering and computer science. Researchers at institutions like the Hungarian Academy of Sciences have developed algorithms based on starling flocking rules to improve drone swarm navigation. These bio-inspired systems enable unmanned aerial vehicles to operate safely in crowded airspace without central command.

Similarly, urban planners use insights from avian flow to design better pedestrian pathways and evacuation protocols. By modeling crowd behavior after bird flocks, cities can reduce congestion and improve safety during large gatherings or emergencies.

Even artificial intelligence benefits from this research. Machine learning models trained on flocking data can simulate complex adaptive systems, aiding everything from stock market analysis to climate modeling.

FAQs About Birds in Flow

What causes birds to fly in flowing patterns?

Birds fly in flowing patterns due to instinctive rules: staying close to neighbors, matching their speed and direction, and avoiding collisions. This creates emergent, fluid-like motion that enhances predator evasion and group cohesion.

Where can I see birds in flow near me?

Check local wetlands, coastal mudflats, or urban parks during migration or winter months. Use eBird.org to find recent reports of murmurations or large shorebird flocks in your region.

Are all black birds that swirl in the sky starlings?

Not always. While European starlings are the most common species forming large murmurations, blackbirds, grackles, and crows may also gather in swirling flocks, particularly in North America.

Do birds in flow migrate together?

Some do, but flowing patterns are more commonly seen during daily commuting between feeding and roosting sites rather than long-distance migration flights.

Can I film a murmuration with a smartphone?

Yes, modern smartphones with stabilized video mode can capture decent footage. For best results, use a tripod, record in landscape orientation, and avoid digital zoom. Early evening light provides optimal visibility.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4