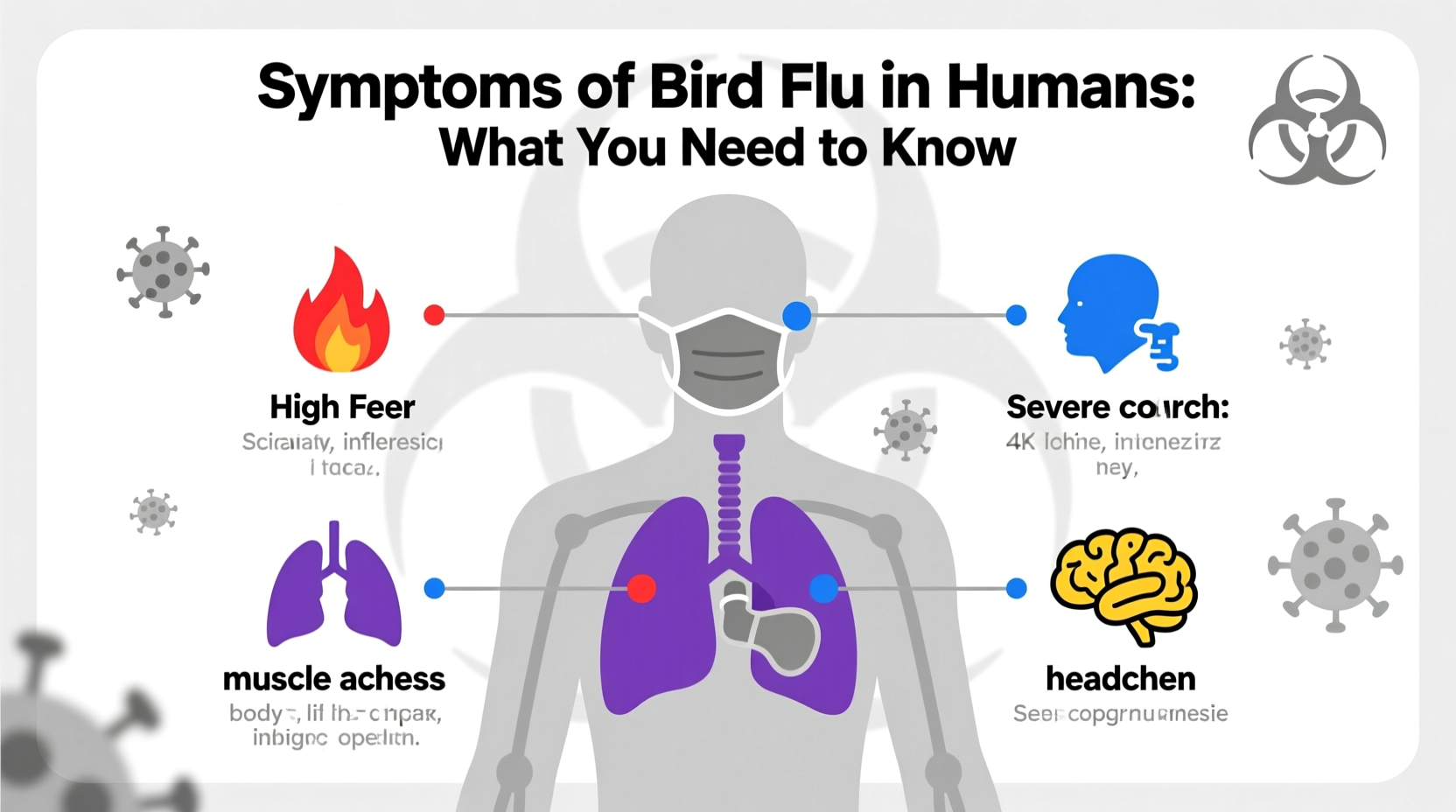

Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, can cause severe illness in humans who come into close contact with infected birds or contaminated environments. The symptoms of bird flu in humans typically appear within 2 to 8 days after exposure and may include high fever (often above 101°F or 38°C), cough, sore throat, muscle aches, headache, fatigue, and shortness of breath. In more severe cases, complications such as pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multi-organ failure, and even death can occur. Understanding the early signs of avian influenza in people is critical for timely medical intervention and containment of potential outbreaks. This article explores the biological mechanisms behind human infection, compares different strains of the virus, discusses risk factors, prevention strategies, global surveillance efforts, and practical advice for birdwatchers and those working with poultry.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Origins and Transmission to Humans

Avian influenza viruses belong to the family Orthomyxoviridae and are primarily adapted to infect birds, especially waterfowl like ducks and geese, which often carry the virus without showing symptoms. There are numerous subtypes based on surface proteins hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N), such as H5N1, H7N9, and H9N2—some of which have demonstrated the ability to cross the species barrier and infect humans.

Human infections usually result from direct contact with infected live or dead birds, exposure to contaminated feces, or breathing in aerosolized particles from poultry markets or farms. While rare, limited human-to-human transmission has been reported, particularly in close household settings, but sustained transmission remains uncommon. Most human cases have occurred in Asia, Africa, and parts of Eastern Europe where backyard farming practices increase exposure risks.

Common Symptoms of Bird Flu in Humans by Strain

The clinical presentation of avian flu in humans varies depending on the viral strain involved. However, there are consistent patterns across outbreaks:

- H5N1: First identified in humans in 1997 in Hong Kong, this strain causes rapid onset of high fever, cough, and difficulty breathing. Diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain are more common than in seasonal flu. Case fatality rates exceed 50% in some regions.

- H7N9: Emerged in China in 2013, this subtype often presents with severe pneumonia and ARDS. Fever and cough are nearly universal; gastrointestinal symptoms are less frequent. Unlike H5N1, many patients do not recall direct bird contact, suggesting possible environmental exposure.

- H9N2: Generally milder, causing conjunctivitis, mild respiratory symptoms, and low-grade fever. It poses concern due to its widespread presence in poultry and potential to reassort with other flu viruses.

Early recognition of these symptom profiles—especially when combined with recent travel history or occupational exposure—is vital for diagnosis and treatment.

How Is Bird Flu Diagnosed in People?

Diagnosis begins with a detailed patient history focusing on recent animal contact, travel, or attendance at live bird markets. Clinicians suspecting avian influenza will order laboratory tests including nasopharyngeal swabs analyzed via RT-PCR (reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction) to detect viral RNA. Blood tests may show lymphopenia (low white blood cell count) and elevated liver enzymes.

Rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDTs) used for seasonal flu are generally ineffective for detecting avian strains. Therefore, specialized testing through public health laboratories is required. Early detection enables prompt isolation, antiviral therapy, and contact tracing to prevent further spread.

Treatment Options and Medical Management

Antiviral medications such as oseltamivir (Tamiflu), zanamivir (Relenza), and peramivir are recommended for treating confirmed or suspected cases of bird flu. These drugs work best when administered within 48 hours of symptom onset, though benefits have been observed even when started later in severe cases.

In addition to antivirals, supportive care is crucial. Hospitalization may be necessary for oxygen therapy, mechanical ventilation, or management of secondary bacterial infections. Corticosteroids are generally avoided unless absolutely needed, as they may worsen outcomes.

Vaccines specifically targeting avian influenza strains (like H5N1) exist in limited supply for stockpiling purposes but are not widely available to the general public. Seasonal flu vaccines do not protect against bird flu.

Who Is at Highest Risk of Contracting Bird Flu?

Certain groups face increased risk of exposure and severe disease:

- Poultry farmers, slaughterhouse workers, and veterinarians handling sick birds

- Individuals visiting live bird markets in endemic areas

- Travelers engaging in rural activities involving domestic fowl

- People with underlying health conditions such as diabetes, chronic lung disease, or weakened immune systems

Children and older adults also tend to experience more severe outcomes once infected. Public health agencies recommend that high-risk individuals avoid contact with birds during known outbreaks and wear protective gear if exposure is unavoidable.

Global Surveillance and Outbreak Trends

The World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and national health bodies maintain global monitoring systems for avian influenza. Since 2003, over 900 human cases of H5N1 have been reported across 20 countries, with Egypt, Indonesia, and Vietnam historically having the highest incidence.

In recent years, clade 2.3.4.4b of H5N1 has caused unprecedented outbreaks in wild birds and poultry across North America and Europe. Although human cases remain rare, the expanding geographic range increases opportunities for spillover events. Enhanced biosecurity measures on farms and real-time genomic sequencing help track mutations that could enhance transmissibility.

| Strain | First Human Cases | Fatality Rate | Geographic Hotspots |

|---|---|---|---|

| H5N1 | 1997 (Hong Kong) | ~53% | Asia, Egypt, Indonesia |

| H7N9 | 2013 (China) | ~40% | Eastern China |

| H9N2 | 1998 (Hong Kong) | Low | Asia, Middle East |

Prevention Strategies for Travelers and Bird Enthusiasts

For birdwatchers and ecotourists traveling to regions experiencing avian flu outbreaks, several precautions reduce risk:

- Avoid touching sick or dead birds; report findings to local wildlife authorities

- Do not visit poultry farms or live bird markets in affected zones

- Wear gloves and masks if handling birds is necessary (e.g., researchers, conservationists)

- Practice strict hand hygiene before eating or touching your face

- Ensure all poultry and eggs are thoroughly cooked (internal temperature ≥165°F or 74°C)

Binoculars and spotting scopes allow safe observation from a distance. Always clean equipment after use in potentially contaminated areas using disinfectant wipes.

Misconceptions About Bird Flu Transmission

Several myths persist about how avian influenza spreads among humans:

- Myth: Eating properly cooked chicken or eggs can give you bird flu.

Fact: No. The virus is destroyed at cooking temperatures above 165°F (74°C). Proper food handling eliminates risk. - Myth: Bird flu spreads easily between people.

Fact: Human-to-human transmission is extremely rare and inefficient. Most cases stem from animal contact. - Myth: All bird species pose equal danger.

Fact: Wild waterfowl often carry the virus asymptomatically, while chickens and turkeys suffer high mortality and pose greater exposure risk when farmed.

What to Do If You Suspect Exposure

If you develop flu-like symptoms within 10 days of being near sick or dead birds, especially in an area with known avian flu activity, take immediate action:

- Isolate yourself from others to prevent potential spread

- Contact your healthcare provider or local health department immediately

- Mention your bird exposure clearly during consultation

- Follow instructions for testing and quarantine

- Avoid travel until cleared by medical professionals

Timely reporting helps public health officials investigate sources and implement control measures.

Future Outlook and Research Directions

Ongoing research focuses on developing universal flu vaccines, improving rapid diagnostics, and enhancing early warning systems using AI-driven surveillance. Scientists monitor genetic changes in circulating strains for mutations that could enable efficient human-to-human transmission—a scenario that would constitute a pandemic threat.

Public awareness, international cooperation, and investment in veterinary and human health infrastructure remain essential to mitigating future risks associated with avian influenza.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can you get bird flu from watching birds in your backyard?

- No, observing birds from a distance poses no risk. Avoid handling dead or sick birds and wash hands after outdoor activities.

- How long does it take for bird flu symptoms to appear in humans?

- Symptoms typically develop within 2 to 7 days after exposure, though incubation can extend up to 10 days in rare cases.

- Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

- There are pre-pandemic vaccines for certain strains like H5N1, but they are not commercially available to the public and are reserved for emergency stockpiles.

- Are migratory birds responsible for spreading bird flu globally?

- Yes, wild migratory birds, especially ducks and shorebirds, play a major role in dispersing the virus across continents through their droppings and natural movements.

- Can pets like cats get bird flu?

- Yes, cats can become infected by eating infected birds. Though rare, feline cases have been documented, particularly during H5N1 outbreaks.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4