When people ask what bird can't fly, they're often surprised by just how many bird species have evolved to live without flight. Over 60 modern bird species are completely flightless, with iconic examples including the ostrich, emu, penguin, kiwi, and cassowary. These birds have adapted to environments where flying was no longer necessary for survival—often due to a lack of natural predators or an abundance of food on the ground. A natural longtail keyword variant like 'which birds cannot fly and why' helps uncover both the biological and evolutionary reasons behind this trait. Flightlessness in birds is not a defect but an adaptation shaped by millions of years of natural selection.

The Evolution of Flightlessness in Birds

Flight is one of the most energy-intensive forms of animal locomotion. For some birds, the cost of maintaining large pectoral muscles, hollow bones, and complex wing structures outweighed the benefits—especially in isolated ecosystems such as islands or remote continents. When early ancestors of today’s flightless birds found themselves in predator-free zones, natural selection favored individuals that invested less energy in flight and more in traits like strong legs for running or diving.

This process, known as evolutionary trade-off, explains why flightless birds often develop enhanced abilities in other areas. For example, the ostrich (the world's largest bird) can sprint up to 45 mph (70 km/h), while penguins ‘fly’ through water with remarkable agility. The loss of flight typically coincides with changes in bone density, muscle distribution, and feather structure—all visible signs of adaptation to terrestrial or aquatic lifestyles.

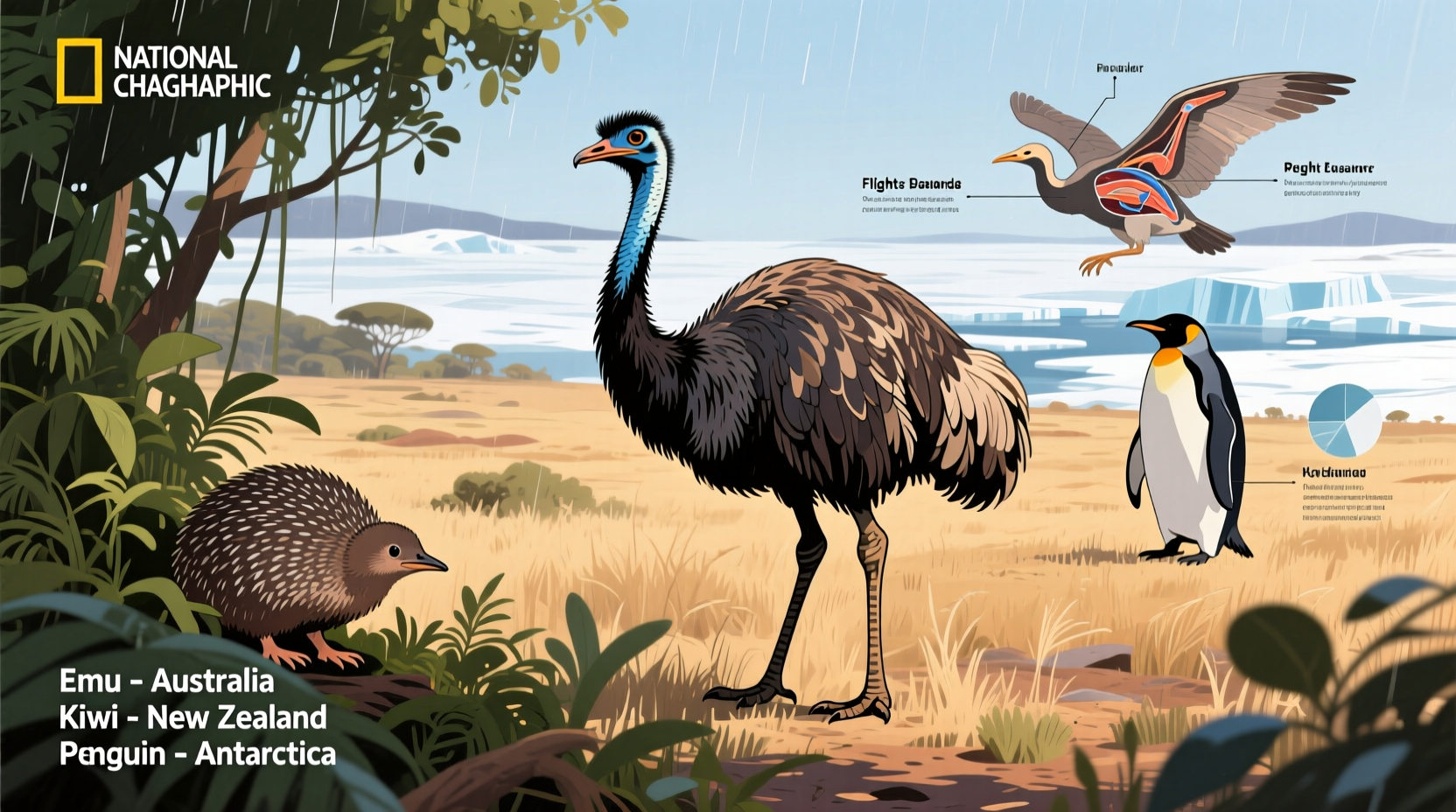

Major Flightless Bird Species Around the World

While there are over 60 flightless species, only a few are widely recognized. Below is a breakdown of the most notable ones, their geographic distribution, and unique characteristics:

| Bird Species | Native Region | Max Speed / Locomotion | Notable Traits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ostrich (Struthio camelus) | Africa | 45 mph (running) | Largest living bird; two-toed feet; excellent vision |

| Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae) | Australia | 31 mph (running) | Second tallest bird; migratory patterns based on rainfall |

| Penguin (various species) | Antarctica, Southern Hemisphere coasts | 15–25 mph (swimming) | Wing-flippers; countershading camouflage; colonial nesting |

| Kiwi (Apteryx spp.) | New Zealand | Slow walker; nocturnal | Nocturnal; hair-like feathers; highly developed sense of smell |

| Cassowary (Casuarius spp.) | New Guinea, northeastern Australia | 30 mph (running) | Powerful kick; helmet-like casque; frugivorous diet |

| Takahe (Porphyrio hochstetteri) | New Zealand | Walks and runs | Rare; rediscovered in 1948; alpine grassland dweller |

Why Can't These Birds Fly? Biological and Anatomical Factors

The inability to fly stems from specific anatomical modifications. Unlike flying birds, which have keeled sternums to anchor flight muscles, flightless birds possess flat or reduced breastbones. Their pectoral muscles are underdeveloped, and their wings are either vestigial or repurposed—such as penguin flippers used for underwater propulsion.

- Bone Density: Flightless birds tend to have denser, heavier bones compared to the hollow skeletons of flying species. This adds mass, making lift-off impossible.

- Feather Structure: Feathers in flightless birds lack the interlocking barbules needed for aerodynamic surfaces. Ostrich plumes, for instance, are soft and蓬松 (fluffy), ideal for display but useless for flight.

- Energy Allocation: Energy once used for flight maintenance is redirected toward reproduction, digestion, or locomotion on land or in water.

These adaptations illustrate how environment shapes physiology. On islands like Madagascar or New Zealand, where mammalian predators were historically absent, birds filled ecological niches usually occupied by mammals—leading to gigantism and flight loss.

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings of Flightless Birds

Beyond biology, flightless birds carry deep cultural significance. In Māori tradition, the kiwi is a national symbol representing resilience and uniqueness. It’s considered a taonga (treasure), and its image appears on currency, military insignia, and conservation campaigns. Similarly, the takahe was believed extinct until its dramatic rediscovery in 1948, becoming a powerful emblem of hope and environmental recovery.

In African folklore, the ostrich features in moral tales about pride and deception. Some stories warn that the ostrich sticks its head in the sand—a myth debunked by science but persistent in popular culture. Penguins, though not native to most human civilizations, have become global icons of perseverance and adaptability, especially in children’s literature and documentaries.

Symbolically, flightless birds challenge our assumptions about progress and ability. They remind us that evolution doesn’t always favor mobility through air; sometimes, staying grounded leads to success.

Where to See Flightless Birds: A Global Guide for Birdwatchers

For avid birders and eco-tourists, observing flightless birds in their natural habitats offers unforgettable experiences. Here are key locations and tips:

- Southern Africa – Ostrich Watching: Visit Namibia’s Namib Desert or South Africa’s Karoo region. Early morning safaris offer the best chance to see ostriches feeding or performing courtship dances. Always maintain distance—ostriches can be aggressive when threatened.

- Australia – Emus and Cassowaries: Emus roam freely across rural Queensland and Western Australia. Cassowaries are rarer and primarily found in Queensland’s Daintree Rainforest. Hire a local guide; these birds are shy and well-camouflaged.

- New Zealand – Kiwi and Takahe Tracking: Due to their nocturnal habits, kiwis are best observed on guided night walks in sanctuaries like Kapiti Island or Zealandia. Takahe can be seen at the Burwood Takahē Centre near Te Anau—reservations required.

- Antarctic & Subantarctic Regions – Penguin Colonies: While full Antarctic expeditions are costly, subantarctic destinations like South Georgia, the Falkland Islands, or Patagonia (Argentina/Chile) host massive penguin colonies. Best viewing months are November to February (austral summer).

Before traveling, check with local wildlife authorities or tour operators for seasonal access, permit requirements, and ethical guidelines. Many sites limit visitor numbers to protect fragile ecosystems.

Conservation Status and Threats Facing Flightless Birds

Ironically, the same isolation that allowed flightlessness to evolve now makes these birds extremely vulnerable. Introduced predators—especially dogs, cats, rats, and stoats—are devastating to ground-nesting species. The extinction of the moa (a giant flightless bird in New Zealand) within a century of Polynesian arrival is a stark example.

Today, several flightless birds remain endangered:

- Kiwi: All five species are declining due to predation and habitat loss. Conservation programs use predator-proof fencing and captive breeding.

- Cassowary: Classified as Vulnerable by IUCN. Habitat fragmentation from agriculture and urban development threatens populations in Queensland.

- Takahe: Once thought extinct, fewer than 400 individuals exist today. Intensive management includes translocation to predator-free islands.

Climate change also poses risks. Rising sea levels threaten low-lying penguin rookeries, while changing temperatures affect food availability. Supporting reputable conservation organizations like the Department of Conservation (New Zealand) or BirdLife International can help protect these unique species.

Common Misconceptions About Non-Flying Birds

Several myths persist about flightless birds, often stemming from outdated beliefs or misinterpretations:

- Myth: Ostriches bury their heads in the sand.

Truth: They lower their necks to the ground to blend in or inspect nests. From a distance, this looks like head-burying. - Myth: All penguins live in Antarctica.

Truth: Only a few species, like the Emperor penguin, breed there. Others inhabit temperate zones like the Galápagos or South Africa. - Myth: Flightless birds are primitive or inferior.

Truth: They are highly specialized. Evolution doesn’t rank species—it adapts them to environments. - Myth: If a bird has wings, it must be able to fly.

Truth: Wings serve multiple purposes: balance (ostrich), swimming (penguin), thermoregulation, and mating displays.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What bird can't fly but runs fast?

- The ostrich is the fastest flightless bird, reaching speeds up to 45 mph (70 km/h) over short distances.

- Are all penguins unable to fly?

- Yes, all 18 recognized penguin species are completely flightless, though they are expert swimmers using their wings as flippers.

- Can any flightless birds swim?

- Yes—penguins are fully aquatic and ‘fly’ underwater. The steamer duck of South America is another flightless bird capable of swimming powerfully.

- Why did flightless birds evolve on islands?

- Islands often lacked terrestrial predators, reducing the need for escape via flight. With abundant food and safety, energy could be redirected into larger body size and ground-based survival strategies.

- Is the chicken a flightless bird?

- Domestic chickens can flutter short distances but are largely flightless due to selective breeding for meat production. Wild junglefowl (their ancestors) can fly better, though still not for long durations.

In conclusion, asking what bird can't fly opens a window into evolutionary biology, cultural symbolism, and global biodiversity. From the towering ostrich to the elusive kiwi, flightless birds demonstrate nature’s capacity for innovation beyond the skies. Whether you’re a student, a birder, or simply curious, understanding these remarkable creatures enriches our appreciation of life on Earth.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4