Flightless birds are species that have evolved without the ability to fly, including well-known examples such as ostriches, emus, cassowaries, rheas, kiwis, and penguins. These birds represent a fascinating adaptation in avian evolution where flightlessness developed due to lack of predators, abundant ground resources, or specialized ecological niches. Among the most searched terms related to this topic is 'what birds are flightless and why can't they fly anymore?' — a question that blends curiosity about biology with evolutionary insight.

Understanding Flightless Birds: An Evolutionary Perspective

Flightless birds belong to a group known as ratites (with the exception of penguins), which includes some of the largest and most distinctive birds on Earth. Ratites lack a keel on their sternum — the bone structure essential for anchoring flight muscles — making powered flight impossible. This anatomical difference is central to understanding what birds are flightless and how they survive without one of the defining traits of birds: flight.

The loss of flight has occurred independently across multiple bird lineages, particularly on isolated islands or continents where predation pressure was historically low. For example, New Zealand's moa birds — now extinct — lived without mammalian predators for millions of years, allowing them to grow large and lose flight capability. Similarly, the Galápagos Islands' flightless cormorant evolved its condition due to rich marine food sources close to shore, reducing the need for aerial mobility.

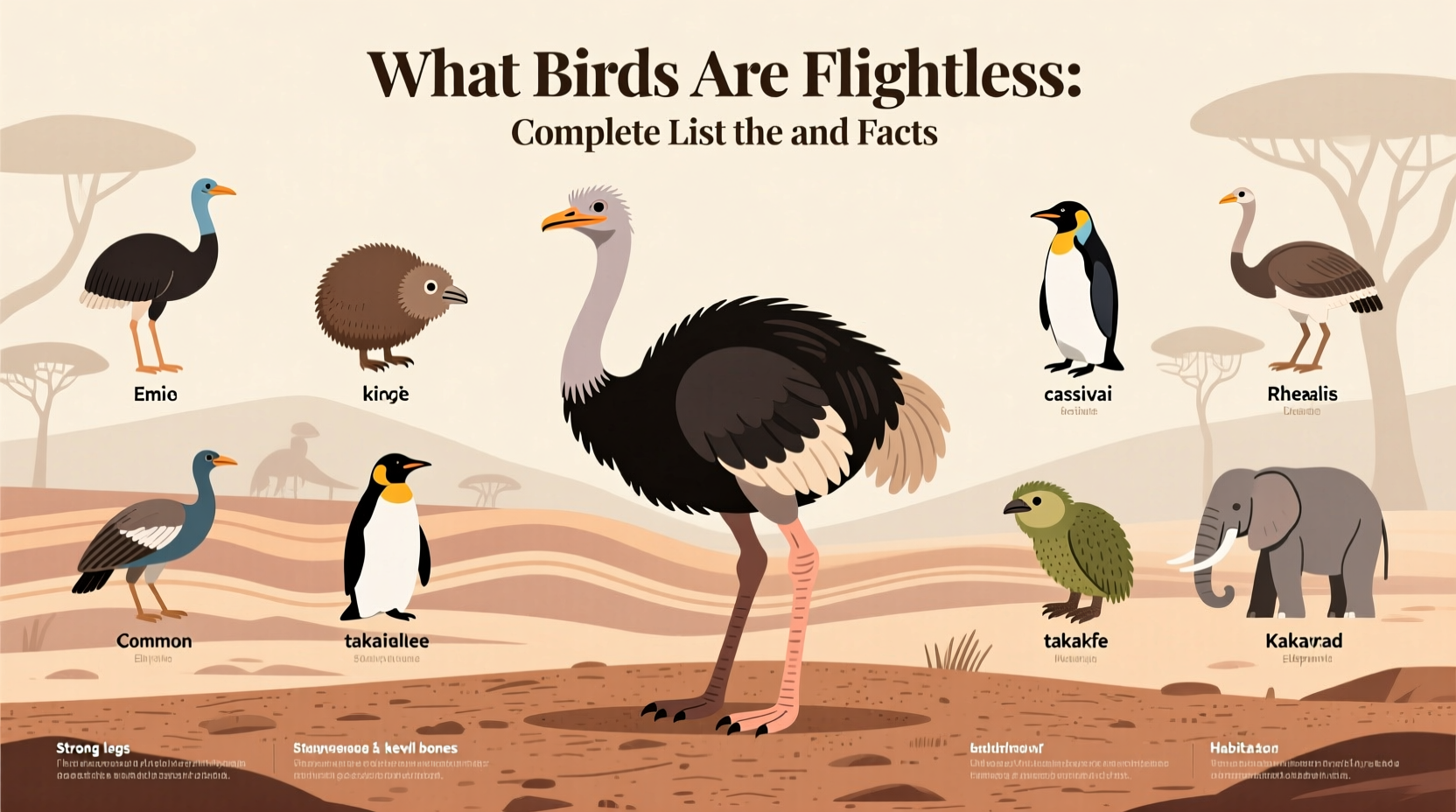

List of Modern Flightless Bird Species

Today, there are approximately 60 extant species of flightless birds, ranging from towering ostriches to small kiwis. Below is a comprehensive table listing major flightless bird species by continent and family:

| Bird Name | Scientific Name | Native Region | Family | Average Height | Conservation Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ostrich | Struthio camelus | Africa | Struthionidae | 2.1–2.8 m | Least Concern |

| Emu | Dromaius novaehollandiae | Australia | Dromaiidae | 1.5–1.9 m | Least Concern |

| Southern Cassowary | Casuarius casuarius | New Guinea, NE Australia | Casuariidae | 1.5–1.8 m | Vulnerable |

| Greater Rhea | Rhea americana | South America | Rheidae | 1.3–1.5 m | Near Threatened |

| Kiwi (Brown Kiwi) | Apteryx mantelli | New Zealand | Apterygidae | 0.4–0.5 m | Vulnerable |

| Adélie Penguin | Pygoscelis adeliae | Antarctica | Spheniscidae | 0.7 m | Least Concern |

| Flightless Cormorant | Phalacrocorax harrisi | Galápagos Islands | Phalacrocoracidae | 0.9–1.0 m | Vulnerable |

| Takahe | Porphyrio hochstetteri | New Zealand | Porphyriidae | 0.6–0.7 m | Endangered |

Why Can't These Birds Fly? The Biology Behind Flightlessness

To understand what birds are flightless, it's crucial to examine the biological adaptations that make flight impossible. Most flying birds have lightweight skeletons, strong pectoral muscles, and asymmetrical flight feathers. In contrast, flightless birds often exhibit:

- Reduced wing size: Wings may be vestigial or used for balance, display, or swimming (in penguins).

- Heavy, dense bones: Unlike the hollow bones of flying birds, flightless species tend to have solid bones, increasing mass but enhancing strength for running or diving.

- Underdeveloped pectoral muscles: Without the need to power flight, these muscles shrink over generations.

- Lack of a sternal keel: This ridge on the breastbone anchors flight muscles; its absence confirms flightlessness in ratites.

Penguins, though flightless, use their wings as flippers to 'fly' underwater, showcasing an evolutionary trade-off between aerial and aquatic locomotion. Their bodies are streamlined for efficient swimming, capable of reaching speeds up to 15 mph beneath the surface.

Habitats and Geographic Distribution

Flightless birds are not evenly distributed globally. Their presence correlates strongly with isolation and environmental stability. Key regions include:

- Africa: Home to the ostrich, the world’s largest and fastest-running bird (up to 70 km/h).

- Australia and New Guinea: Host emus and cassowaries, both powerful runners with sharp claws used for defense.

- South America: The rhea inhabits grasslands and savannas, filling an ecological niche similar to deer in other ecosystems.

- New Zealand: Once home to the giant moa (extinct), today it protects rare species like the kiwi and takahe through intensive conservation programs.

- Antarctic and Subantarctic Zones: Penguins dominate here, adapted to extreme cold with thick blubber and waterproof plumage.

- Galápagos Islands: The only flightless cormorant lives here, having lost flight due to minimal predation and rich coastal feeding grounds.

Survival Strategies and Ecological Roles

Despite lacking flight, many flightless birds thrive using alternative survival strategies:

- Speed and endurance: Ostriches and rheas rely on powerful legs to outrun predators.

- Cryptic behavior: Kiwis are nocturnal and have excellent hearing and smell, helping them avoid danger.

- Aggressive defense: Cassowaries possess dagger-like claws and will attack if threatened.

- Parental investment: Male emus incubate eggs and care for chicks for up to six months, increasing offspring survival.

In ecosystems, flightless birds play vital roles as seed dispersers, insect controllers, and prey for apex predators. Their extinction could disrupt food webs and reduce biodiversity.

Threats Facing Flightless Birds Today

While natural flightlessness evolved under safe conditions, modern threats — primarily human-driven — place these species at high risk:

- Introduced predators: Cats, rats, dogs, and stoats devastate ground-nesting birds like kiwis and takahē.

- Habitat destruction: Deforestation and urban expansion reduce available territory.

- Climate change: Rising temperatures affect breeding cycles and food availability, especially for penguins dependent on sea ice.

- Low genetic diversity: Small populations increase vulnerability to disease and inbreeding.

For instance, the kakapo — a flightless parrot native to New Zealand — is critically endangered with fewer than 250 individuals remaining. Conservationists use radio tracking, supplementary feeding, and assisted breeding to sustain the population.

How to Observe Flightless Birds Safely and Ethically

For birdwatchers and eco-tourists interested in seeing flightless birds in the wild, ethical observation practices are essential:

- Maintain distance: Never approach or attempt to touch wild birds. Use binoculars or telephoto lenses.

- Follow local guidelines: Parks and reserves often have specific rules to protect sensitive species.

- Stay on marked trails: Avoid trampling nests or disturbing habitats.

- Support conservation efforts: Visit sanctuaries that contribute to protection programs (e.g., Pūkaha National Wildlife Centre in New Zealand).

- Report sightings responsibly: Use citizen science platforms like eBird to share data without revealing exact nest locations.

Common Misconceptions About Flightless Birds

Several myths persist about flightless birds. Addressing them helps clarify what birds are flightless and why:

- Myth: All flightless birds are large. Reality: While ostriches are huge, kiwis and wekas are relatively small.

- Myth: Flightless birds are lazy or poorly adapted. Reality: They are highly specialized for their environments.

- Myth: Penguins are mammals because they swim. Reality: Penguins are birds — they lay eggs, have feathers, and are warm-blooded.

- Myth: Flightlessness means weakness. Reality: Many flightless birds are apex survivors in their ecosystems.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Are all flightless birds part of the ratite group?

- No. While ostriches, emus, and kiwis are ratites, penguins and the flightless cormorant are not. Penguins belong to a separate lineage adapted for aquatic life.

- Can any flightless birds glide or jump?

- No true flightless bird can glide. However, some, like young kiwis, may hop short distances. Ostriches use wings for balance during sharp turns while running.

- Why did flightlessness evolve in so many island species?

- Islands often lacked terrestrial predators and offered stable food sources, reducing the need for escape via flight. Over time, energy saved from not maintaining flight muscles was redirected toward reproduction and size.

- Do flightless birds have wings at all?

- Yes, most do — but they are reduced. Ostrich wings are large and used for display; penguin wings are flippers; kiwi wings are tiny and hidden under fur-like feathers.

- Could climate change cause more birds to become flightless?

- Unlikely in the short term. Flightlessness evolves over millions of years under stable conditions. Current rapid environmental changes are more likely to drive extinction than adaptation.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4