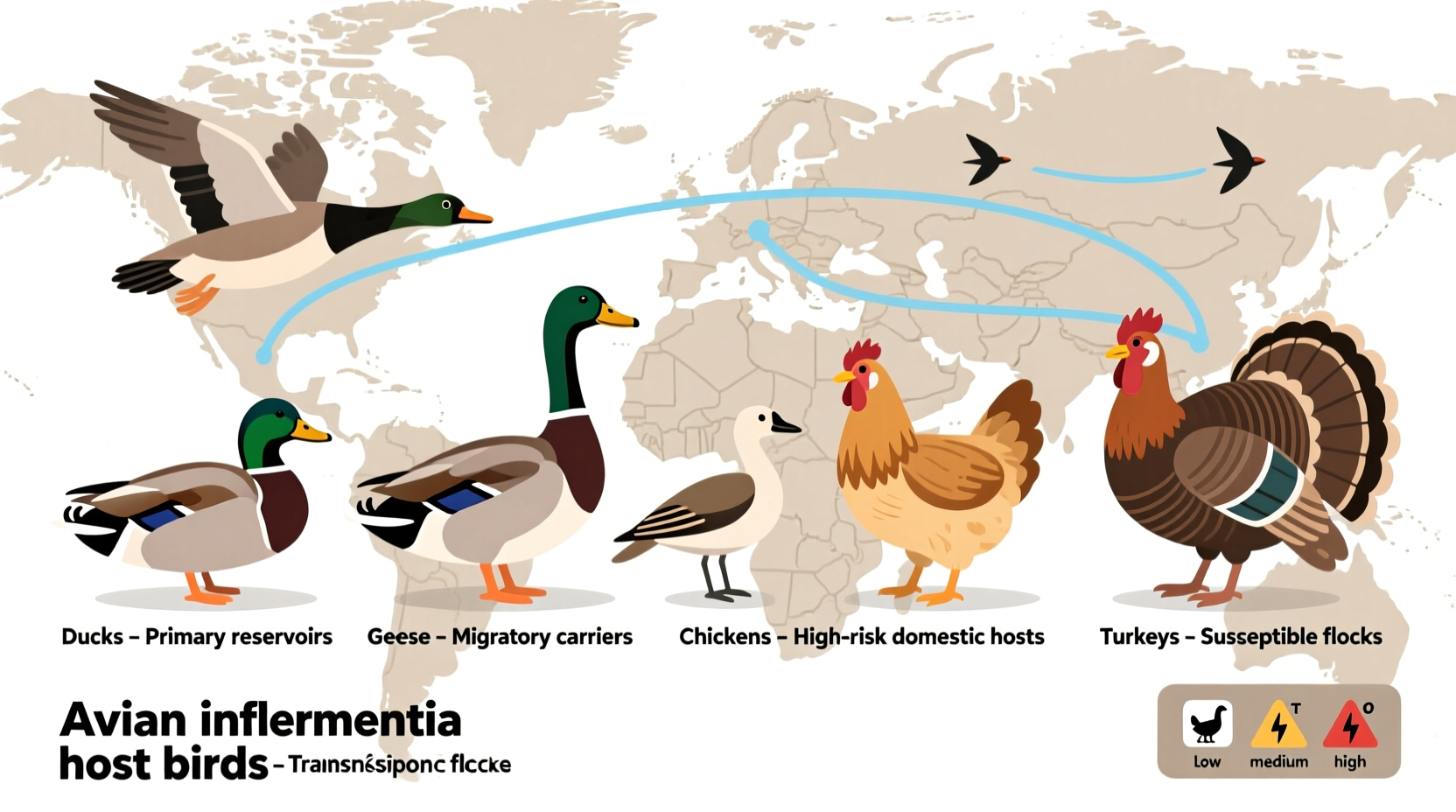

Birds that carry bird flu primarily include wild waterfowl such as ducks, geese, and swans, which are natural reservoirs of avian influenza viruses. These species often show no symptoms but can spread the virus through saliva, nasal secretions, and feces. The question of what birds carry the bird flu is central to understanding outbreaks in both wild populations and commercial poultry farms. Migratory birds, especially those in the order Anseriformes (ducks, geese, swans) and Charadriiformes (shorebirds like gulls and terns), play a significant role in the global dissemination of the virus. While domestic poultry—particularly chickens and turkeys—are highly susceptible and can suffer severe illness or death from infection, they are generally considered secondary hosts rather than long-term carriers.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Types and Transmission

Avian influenza, commonly known as bird flu, refers to a group of influenza A viruses that primarily infect birds. These viruses are classified based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, leading to numerous combinations such as H5N1, H7N9, and H5N8. Some strains cause mild illness (low pathogenic avian influenza, or LPAI), while others—like certain H5 and H7 subtypes—are highly pathogenic (HPAI) and can lead to rapid mortality in poultry flocks.

The primary mode of transmission among birds is through direct contact with infected individuals or contaminated environments. Water sources frequented by wild birds, shared feeders, and improperly cleaned equipment on farms can all serve as transmission routes. Because many wild birds shed the virus asymptomatically, especially during migration, tracking and controlling its spread becomes particularly challenging.

Wild Birds That Carry Bird Flu: Natural Reservoirs

Among the various bird species, certain groups are more likely to carry and transmit bird flu due to their biology and behavior:

- Ducks (Anatidae family): Particularly dabbling ducks like mallards, northern pintails, and American black ducks, are major carriers of avian influenza. They frequently inhabit wetlands where virus particles can persist in water for extended periods.

- Geese and Swans: These migratory birds travel vast distances across continents, potentially introducing new viral strains into previously unaffected regions.

- Shorebirds and Waders: Species such as sandpipers, plovers, and curlews have also tested positive for avian influenza, though they typically carry lower viral loads compared to waterfowl.

- Gulls and Terns: Often overlooked, some gull species can harbor and excrete the virus, especially in coastal areas near aquaculture sites or landfills.

It’s important to note that not all individual birds within these species are infected at any given time. Prevalence varies seasonally, peaking during spring and fall migrations when large numbers congregate at stopover sites.

Domestic Poultry and the Risk of Outbreaks

While wild birds are the main reservoirs of avian influenza, domesticated birds—especially chickens, turkeys, quails, and guinea fowls—are extremely vulnerable to infection. Unlike wild waterfowl, which may remain asymptomatic, poultry often develop severe respiratory distress, neurological signs, decreased egg production, and high mortality rates when exposed to HPAI strains.

Outbreaks in commercial farms usually occur through indirect transmission: wild birds contaminating feed, water, or farm equipment; workers transporting the virus on clothing or boots; or proximity to wetlands inhabited by migratory species. Once introduced, the virus can spread rapidly within dense populations, prompting mass culling to prevent further transmission.

In backyard flocks, biosecurity measures are often less stringent, increasing the risk of exposure. Free-ranging chickens that come into contact with wild bird droppings or shared water sources are particularly at risk. Therefore, answering the query what birds carry the bird flu must include both wild reservoirs and susceptible domestic species.

Do All Bird Species Pose a Risk?

No—not all bird species are equally involved in carrying or spreading avian influenza. Passerines (perching birds like sparrows, robins, and starlings) rarely test positive for the virus, and when they do, it's usually in low quantities. Raptors such as eagles, hawks, and owls may become infected by preying on sick birds but are not considered maintenance hosts.

Pigeons and doves (Columbidae family) have shown resistance to most strains of bird flu under experimental conditions, although isolated cases have been reported in crowded urban settings. Similarly, songbirds and hummingbirds are not known to play a significant role in transmission.

Thus, while concerns about what birds carry the bird flu might prompt people to avoid all birdwatching activities, the actual risk remains concentrated in specific ecological niches involving waterfowl and poultry operations.

Geographic Patterns and Seasonal Trends

Bird flu distribution follows migratory flyways. In North America, the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific Flyways serve as corridors for virus movement each year. Surveillance programs monitor sentinel species along these routes to detect emerging strains early.

Seasonality plays a key role: outbreaks in wild birds tend to peak between September and December and again from March to May—coinciding with southward and northward migrations. In temperate climates, cooler temperatures and stable freshwater bodies allow the virus to survive longer outside a host.

Internationally, regions with intensive poultry farming adjacent to wetlands—such as parts of Southeast Asia, Egypt, and Eastern Europe—experience recurring outbreaks. Climate change, habitat loss, and increased human-wildlife interaction may be contributing to more frequent spillover events.

| Bird Group | Role in Bird Flu Spread | Commonly Affected Species | Symptoms Observed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waterfowl (Ducks, Geese, Swans) | Primary reservoirs; asymptomatic carriers | Mallard, Canada goose, mute swan | Rarely show symptoms |

| Shorebirds | Occasional carriers; minor role | Sanderling, killdeer, dunlin | No visible illness |

| Domestic Chickens/Turkeys | Highly susceptible; amplify virus | Broilers, layers, heritage breeds | Respiratory distress, sudden death |

| Raptors | Secondary infections via predation | Bald eagle, red-tailed hawk | Neurological signs, weakness |

| Pigeons/Doves | Low susceptibility | Rock pigeon, mourning dove | Typically resistant |

Human Health Implications and Zoonotic Potential

Although bird flu primarily affects avian species, some strains—including H5N1, H7N9, and H5N6—have caused sporadic infections in humans. Most cases result from close contact with infected poultry, such as handling sick birds, slaughtering, or visiting live bird markets. Human-to-human transmission remains rare and inefficient, limiting pandemic potential so far.

Public health agencies recommend avoiding contact with dead or sick birds, wearing protective gear when handling poultry, and thoroughly cooking eggs and meat to destroy any virus present. Despite fears fueled by media coverage, the average person’s risk of contracting bird flu remains very low.

Prevention and Biosecurity Measures

For poultry owners and wildlife managers, preventing bird flu transmission requires proactive biosecurity practices:

- Isolate domestic birds: Keep chickens and turkeys indoors or in enclosed runs, especially during peak migration seasons.

- Control access: Limit visitors to poultry areas and require disinfection of footwear and equipment.

- Monitor water sources: Prevent wild birds from accessing drinking water intended for domestic flocks.

- Report sick or dead birds: Contact local wildlife authorities or agricultural departments if unusual mortality is observed.

- Vaccination (where applicable): In some countries, vaccines are used in high-risk areas, though they don’t eliminate infection entirely and complicate surveillance efforts.

Surveillance and Global Monitoring Efforts

Organizations such as the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and national agencies like the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) conduct ongoing surveillance to track avian influenza in both wild and domestic populations. Programs like the USDA’s Wild Bird Surveillance Program test thousands of samples annually to detect emerging threats.

Citizen scientists and birdwatchers can contribute by reporting unusual bird deaths through platforms like eBird or government hotlines. Early detection helps authorities implement containment strategies before widespread outbreaks occur.

Common Misconceptions About What Birds Carry Bird Flu

Several myths persist about which birds are responsible for spreading bird flu:

- Myth: All wild birds carry bird flu.

Fact: Only certain species, mainly waterfowl and shorebirds, act as regular carriers. Most wild birds never encounter the virus. - Myth: Pet birds like parrots or canaries are at high risk.

Fact: These species are rarely affected unless housed near infected poultry. - Myth: Eating chicken or eggs spreads bird flu.

Fact: Proper cooking destroys the virus. No human cases have been linked to properly prepared poultry products.

FAQs: Common Questions About Birds That Carry Bird Flu

- Can songbirds carry bird flu?

- Songbirds are not significant carriers. While rare infections have occurred, they do not contribute meaningfully to virus spread.

- Are pigeons a threat for spreading bird flu?

- No, pigeons are naturally resistant to most avian influenza strains and are not considered a public health risk in this context.

- How do ducks carry bird flu without getting sick?

- Ducks have evolved immune adaptations that allow them to tolerate the virus in their intestinal tract without showing clinical signs, making them ideal reservoirs.

- Should I stop feeding wild birds during an outbreak?

- If HPAI is confirmed locally, consider pausing bird feeding to reduce congregation and potential transmission at feeders.

- Can bird flu spread to mammals?

- Yes—sporadic cases have been reported in foxes, raccoons, seals, and even domestic cats that consumed infected birds. However, sustained mammalian transmission remains uncommon.

In conclusion, understanding what birds carry the bird flu involves recognizing the distinct roles played by different avian species. Wild waterfowl serve as the primary reservoirs, maintaining and dispersing the virus globally through migration. Domestic poultry, while not natural carriers, are highly vulnerable and can amplify outbreaks with serious economic and animal welfare consequences. By combining scientific knowledge with practical prevention strategies, stakeholders—from farmers to birdwatchers—can help mitigate the impact of avian influenza on ecosystems, agriculture, and public health.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4