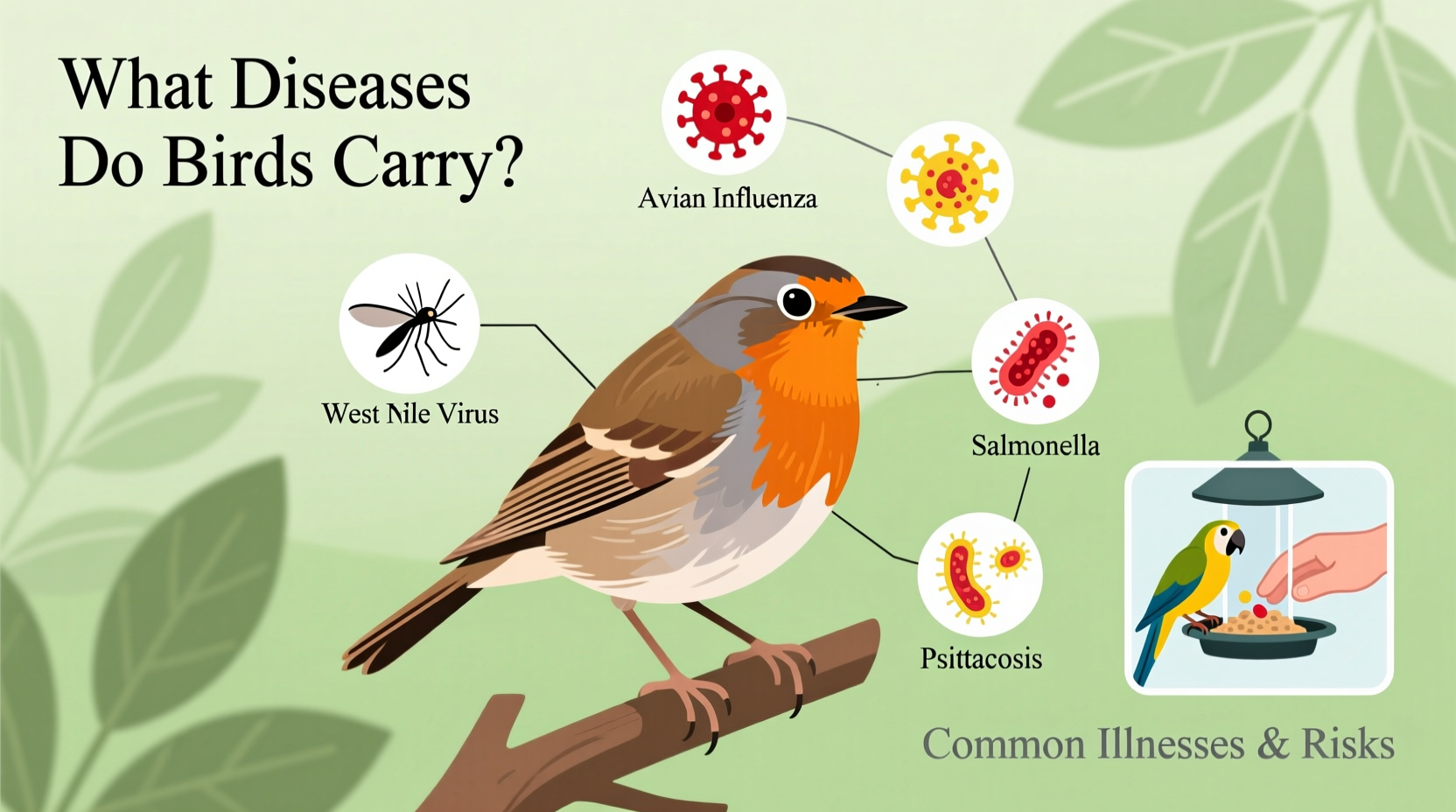

Birds can carry a variety of diseases that may pose health risks to humans and other animals. Understanding what diseases do birds carry is essential for bird enthusiasts, pet owners, and those who live in areas with high bird populations. While most wild birds are not inherently dangerous, certain species can transmit bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic infections—especially under conditions of close contact or poor sanitation. Among the most well-known illnesses associated with birds are avian influenza (bird flu), psittacosis (parrot fever), salmonellosis, histoplasmosis, and West Nile virus. These diseases vary in transmission methods, severity, and geographic prevalence, making awareness and preventive practices crucial.

Common Bacterial Diseases Transmitted by Birds

Several bacterial infections originate from birds and can be passed to humans through direct contact, inhalation of contaminated dust, or exposure to droppings. One of the most significant is Chlamydia psittaci, which causes psittacosis, also known as parrot fever. This disease primarily affects parrots, cockatiels, parakeets, and pigeons but can infect humans who handle sick birds or breathe in dried fecal matter or respiratory secretions.

Symptoms in humans include fever, chills, headache, muscle aches, and a dry cough. In severe cases, it can lead to pneumonia. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that although rare, psittacosis outbreaks often occur among people working in aviaries, pet stores, or poultry farms. Proper ventilation, protective gear, and quarantining new birds are effective ways to reduce risk.

Another common bacterial illness is Salmonella infection. Wild birds such as songbirds and waterfowl, as well as backyard poultry like chickens and ducks, can shed Salmonella in their droppings without appearing ill. Humans typically become infected by handling birds, touching contaminated surfaces, or consuming food exposed to bird feces. Children are especially vulnerable due to hand-to-mouth behaviors. Preventive steps include washing hands after bird contact, cleaning feeders regularly, and keeping poultry outside living areas.

Viral Infections Linked to Avian Species

Among the most widely recognized viruses carried by birds is avian influenza, commonly referred to as bird flu. Certain strains, such as H5N1 and H7N9, have caused global concern due to their potential to jump from birds to humans. Most human cases result from direct contact with infected poultry or contaminated environments, particularly in rural farming regions of Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe.

While person-to-person transmission remains limited, public health agencies closely monitor these viruses for signs of mutation that could enable widespread human spread. Symptoms range from mild respiratory issues to severe pneumonia and multi-organ failure. Travelers visiting areas experiencing bird flu outbreaks should avoid live bird markets and report any feverish illness following exposure.

West Nile virus is another bird-borne illness, though it requires a mosquito vector for transmission to humans. Birds—especially crows, jays, and raptors—serve as reservoir hosts. Mosquitoes bite infected birds and then transmit the virus to people. Most individuals experience no symptoms, but about 20% develop fever, rash, joint pain, and fatigue. Less than 1% suffer neuroinvasive disease, including meningitis or encephalitis. Reducing mosquito breeding sites and using insect repellent are key preventive strategies.

Fungal Diseases Associated with Bird Droppings

Fungal infections represent another category of illness linked to birds, primarily stemming from environmental contamination. Histoplasmosis is caused by inhaling spores of the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum, which thrives in soil enriched with bird or bat droppings. It's particularly prevalent in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys in the United States.

People at highest risk include construction workers, cave explorers, and gardeners disturbing contaminated soil. Initial symptoms mimic the flu, but chronic lung disease can develop in immunocompromised individuals. To minimize exposure, wet down soil before digging, wear N95 respirators in high-risk zones, and avoid nesting areas under bridges or in abandoned buildings where large flocks roost.

Cryptococcosis is another fungal disease associated with bird droppings, especially those of pigeons. The causative agent, Cryptococcus neoformans, lives in dried excrement and becomes airborne when disturbed. While healthy people rarely get sick, those with weakened immune systems—such as HIV/AIDS patients—are at increased risk of developing life-threatening meningitis. Sealing building ledges to prevent roosting and cleaning droppings with disinfectants can help control this hazard.

Parasites and Zoonotic Risks from Birds

Birds can host various external and internal parasites that occasionally affect humans. Mites and lice are commonly found on wild and domestic birds. Although most species are host-specific and don’t survive long on humans, some—like the tropical fowl mite—can cause temporary skin irritation. Infestations usually resolve once the bird source is removed.

Internal parasites such as roundworms and tapeworms are generally not directly transmissible to humans but can contaminate environments if droppings are not cleaned properly. More concerning is the indirect role birds play in spreading ticks and fleas that carry Lyme disease or typhus, though birds themselves are not primary vectors.

Diseases Carried by Specific Bird Groups

Different bird species carry distinct pathogens based on habitat, diet, and behavior:

- Pigeons and Doves: Known carriers of Chlamydia psittaci, Cryptococcus, and Salmonella. Their urban presence increases human exposure risk.

- Waterfowl (ducks, geese): Frequently harbor avian influenza and Salmonella. Feeding them in parks can concentrate droppings and elevate contamination levels.

- Backyard Chickens: Increasingly popular, yet they can carry Salmonella and E. coli even when appearing healthy. CDC advises against kissing or snuggling pet poultry.

- Parrots and Cage Birds: Prone to psittacosis; require quarantine and veterinary screening upon acquisition.

- Raptors and Scavengers: Can carry bacteria from carrion, posing risks during rehabilitation efforts.

How Bird Diseases Affect Pets and Livestock

Domestic animals are also susceptible to diseases transmitted by wild birds. Cats and dogs may contract salmonellosis or toxoplasmosis by eating infected birds or feces. Poultry farms face major economic threats from avian influenza outbreaks, which can decimate flocks and trigger trade restrictions. Biosecurity measures—including secure housing, rodent control, and limiting wild bird access—are critical for commercial operations.

Vaccination programs exist for certain poultry diseases, but none are universally effective against all strains. Backyard flock owners should register their birds with local agricultural authorities and report sudden deaths immediately.

Prevention and Safety Practices for Bird Enthusiasts

Millions enjoy birdwatching, feeding, and keeping pet birds. With proper precautions, the risks of disease transmission are low. Key safety tips include:

- Wear gloves and masks when cleaning cages, nests, or droppings.

- Wash hands thoroughly with soap and water after handling birds or equipment.

- Clean bird feeders and baths weekly using a 10% bleach solution to prevent bacterial buildup.

- Avoid feeding birds by hand, especially in public spaces.

- Keep pet birds isolated from wild ones and schedule regular vet checkups.

- Do not touch sick or dead birds with bare hands; report them to local wildlife agencies.

Myths and Misconceptions About Bird-Borne Diseases

Despite real risks, several myths exaggerate the danger birds pose:

- Myth: All birds carry deadly diseases.

Fact: Most birds are healthy and only pose risks under specific conditions. - Myth: Bird feeders are always unsafe.

Fact: Properly maintained feeders present minimal risk and support biodiversity. - Myth: You can catch bird flu from eating chicken.

Fact: Fully cooked poultry is safe; the virus is destroyed at normal cooking temperatures. - Myth: Only dirty cities have disease-carrying birds.

Fact: Pathogens exist in rural, suburban, and urban areas alike.

Regional Variations in Bird Disease Prevalence

The types and frequency of bird-borne diseases vary geographically. For example:

- In North America, histoplasmosis hotspots align with river basins rich in bird roosts.

- In Southeast Asia, avian influenza remains endemic in backyard poultry flocks.

- In Europe, West Nile virus has expanded northward due to climate change and migratory patterns.

- In Australia, outbreaks of avian paramyxovirus affect both wild and domestic birds.

Local health departments and ornithological societies often publish regional advisories. Staying informed through official channels helps individuals adapt prevention strategies accordingly.

| Disease | Cause | Transmission Route | At-Risk Groups | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psittacosis | Chlamydia psittaci | Inhalation of dried droppings/respiratory secretions | Bird handlers, pet shop workers | Quarantine new birds, use PPE |

| Avian Influenza | Influenza A viruses (H5N1, H7N9) | Contact with infected birds or surfaces | Farmers, travelers to outbreak zones | Avoid live markets, cook poultry fully |

| Salmonellosis | Salmonella spp. | Fecal-oral route, contaminated surfaces | Children, elderly, immunocompromised | Handwashing, clean feeders weekly |

| Histoplasmosis | Histoplasma capsulatum | Inhaling spores from soil with bird droppings | Construction workers, spelunkers | Wet soil before digging, wear masks |

| West Nile Virus | Flavivirus | Mosquito bite after bird infection | Outdoor workers, older adults | Use repellent, eliminate standing water |

When to Seek Medical Attention After Bird Exposure

If you’ve had close contact with birds—especially sick or dead ones—and develop symptoms such as fever, cough, headache, or difficulty breathing within 10 days, seek medical care promptly. Inform your healthcare provider about the bird exposure, as this aids diagnosis. Early treatment improves outcomes, particularly for conditions like psittacosis or fungal infections.

Additionally, report unusual bird mortality events to local wildlife authorities. Sudden die-offs may signal emerging diseases requiring surveillance and containment.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can I get sick from touching a wild bird?

- Yes, especially if the bird is sick or its droppings are present. Always wash hands afterward and avoid direct contact.

- Are backyard bird feeders dangerous?

- Not if maintained properly. Clean feeders weekly and space them apart to reduce crowding and disease spread.

- Can my pet bird make me sick?

- Pet birds can carry psittacosis or Salmonella. Practice good hygiene and have your bird checked by an avian vet annually.

- Is bird poop harmful to humans?

- Fresh droppings pose minimal risk, but dried feces can release infectious spores or bacteria when inhaled. Handle with caution.

- How do I safely clean up bird droppings?

- Wear gloves and an N95 mask, moisten the area first to prevent aerosolization, then scrub with soapy water or disinfectant.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4