Mites on birds are tiny parasitic arthropods that are often difficult to see with the naked eye, typically measuring less than 1 millimeter in length. If you're wondering what do mites on birds look like, they generally appear as minute, pale, translucent, or whitish specks that may cluster around feather bases, especially near the vent, eyes, and beak. In severe infestations, mite activity can cause visible skin irritation, scaly patches, feather loss, or restlessness in birds. These ectoparasites come in various species-specific forms—such as quill mites, nasal mites, and red mites—and their appearance can vary slightly depending on the host bird and mite type. Understanding what bird mites look like is essential for birdkeepers, wildlife rehabilitators, and backyard bird enthusiasts aiming to maintain avian health.

Biology of Bird Mites: Species and Identification

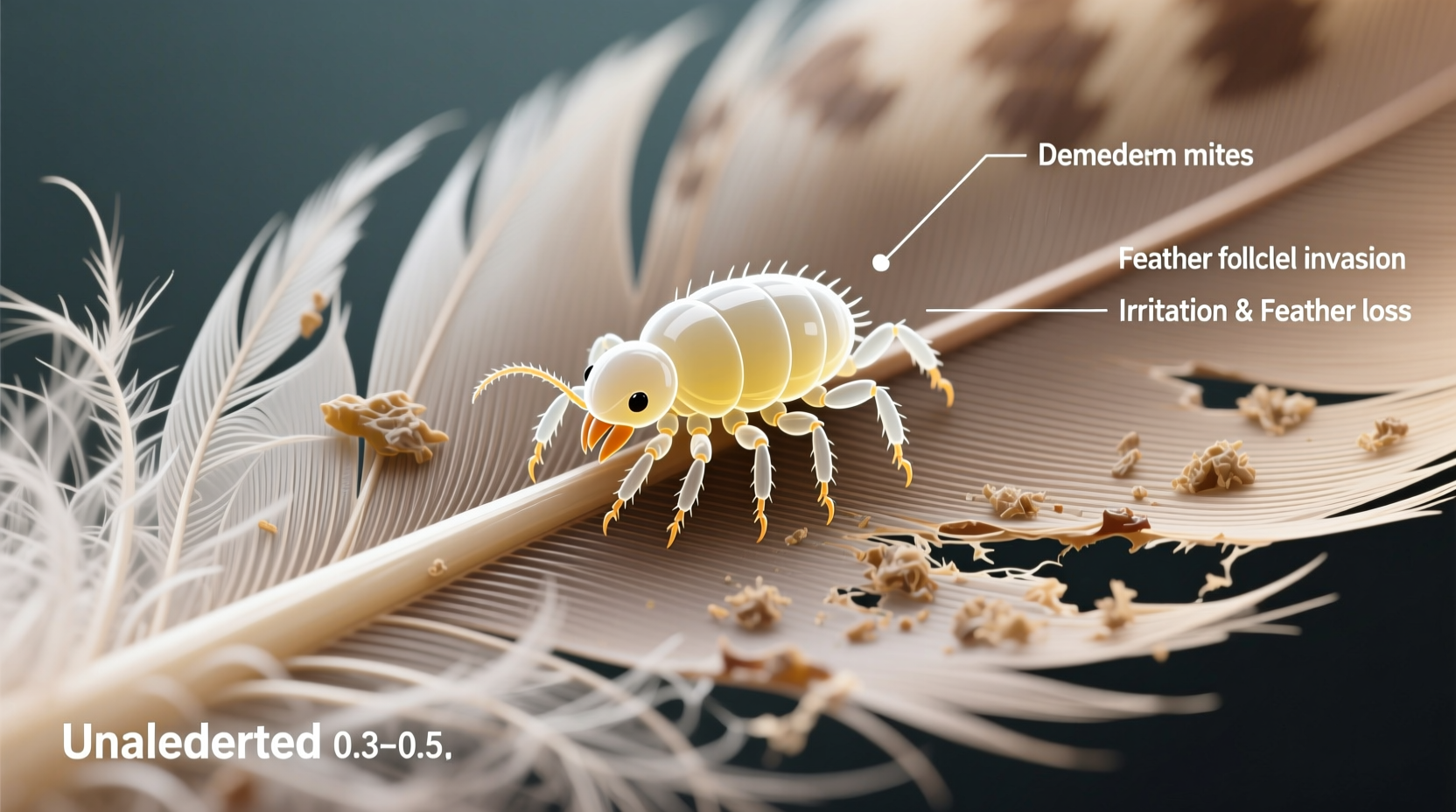

Bird mites belong to several families, including Dermanyssidae (e.g., Dermanyssus gallinae, the red poultry mite), Syringophilidae (quill mites), and Trombiculidae (chiggers). While most are microscopic, some, like the red mite, may become visible to the human eye when engorged with blood, appearing as tiny dark red or black moving dots. Under magnification, mites have eight legs (as adults), oval-shaped bodies, and lack antennae—key features distinguishing them from insects.

Common Types of Mites Found on Birds:

- Red Roost Mite (Dermanyssus gallinae): Pale gray when unfed, turning red or black after feeding. Nocturnal, hiding in cracks during the day.

- Scaly Face and Leg Mite (Knemidokoptes pilae): Causes crusty lesions on beaks and legs; mites themselves burrow and are rarely seen directly.

- Feather Mites: Live on feather surfaces, usually non-parasitic; appear as tiny white specks only visible under a microscope.

- Quill Mites: Reside inside feather shafts; require feather plucking and microscopic examination for detection.

Identification often requires a vet or specialist using skin scrapings, tape impressions, or feather examination under a compound microscope. Misidentification is common, as mites can resemble dandruff, fungal spores, or debris.

Lifecycle and Behavior of Avian Mites

The lifecycle of bird mites includes egg, larva, protonymph, deutonymph, and adult stages. Most complete development within 7–10 days under warm, humid conditions. Red mites, for example, feed at night on resting birds and retreat to nesting materials or crevices during daylight. This behavior makes them hard to detect during routine daytime observation.

Mites reproduce rapidly in favorable environments. A single female Dermanyssus gallinae can lay up to 30 eggs in her lifetime. Because they can survive for several months without a host, abandoned nests or coops can remain infested long after birds have left.

| Mite Type | Size (mm) | Color | Visible Without Magnification? | Primary Host Signs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red Roost Mite | 0.5–1.0 | Pale → Red/Black after feeding | Sometimes (if clustered) | Anemia, agitation, reduced laying |

| Scaly Face Mite | ~0.3 | Translucent | No | Crusty beak, leg deformities |

| Quill Mite | 0.1–0.2 | Clear to white | No | Feather breakage, poor plumage |

| Feather Mite | 0.2–0.5 | White/light brown | Rarely | Minimal; mostly commensal |

Symptoms of Mite Infestation in Birds

Birds infested with mites may show subtle or overt signs depending on severity and species. Early detection improves treatment outcomes. Common symptoms include:

- Restlessness or frequent scratching: Especially at night, which may indicate nocturnal mites.

- Feather damage or excessive preening: Birds may over-preen due to irritation.

- Skin lesions or scaling: Particularly around the face, legs, or vent area.

- Weight loss or lethargy: Resulting from chronic blood loss or stress.

- Anemia: Pale combs or wattles in poultry; labored breathing.

- Nesting avoidance: Birds may refuse to roost if mites are present in nest boxes.

In wild birds, mite loads are often kept in check by natural behaviors such as dust bathing, preening, and seasonal molting. However, captive birds or those in crowded aviaries are more vulnerable to outbreaks.

Habitat and Transmission: How Birds Get Mites

Mites spread through direct contact with infested birds, contaminated nesting materials, or shared perches. Wild birds entering backyard feeders or nesting in eaves can introduce mites to domestic flocks. Rodents or other pests may also carry mites into coops or aviaries.

Common transmission routes include:

- Introduction of new, unquarantined birds

- Use of secondhand cages, perches, or nesting boxes

- Proximity to wild bird nests (e.g., sparrows or starlings in building cavities)

- Poor sanitation in aviaries or breeding facilities

Environmental persistence is a key factor. Red mites can survive for months without feeding, making eradication challenging. They hide in wood cracks, beneath perches, and in nest box seams—areas often overlooked during cleaning.

Diagnosis: Confirming Mite Presence

Visual inspection alone is insufficient for accurate diagnosis. To confirm mite infestation:

- Nighttime inspection with flashlight: Check birds and coop interiors after dark, as red mites are nocturnal feeders.

- White paper test: Place white paper under perches overnight; small moving specks or blood spots in the morning suggest mite activity.

- Veterinary diagnostics: Skin scrapings, feather shaft examination, or PCR testing for species identification.

- Microscopic evaluation: Essential for detecting quill or follicle mites not visible externally.

It's important to differentiate mites from other conditions like lice (which are larger and visible), fungal infections (e.g., ringworm), or nutritional deficiencies causing feather loss.

Treatment Options for Infested Birds

Effective mite control requires treating both the bird and its environment. Never use pesticides labeled for mammals (e.g., permethrin for dogs) without veterinary guidance, as many are toxic to birds.

On-Bird Treatments:

- Ivermectin: Administered orally, topically, or via injection under vet supervision. Effective against many mite species.

- Moxidectin: Longer-lasting alternative, often used in waterfowl and raptors.

- Topical sprays: Avian-safe formulations containing pyrethrins or neem oil—used cautiously to avoid inhalation.

Environmental Treatments:

- Thorough cleaning: Remove all bedding, scrub surfaces with hot water and detergent.

- Heat treatment: Bake wooden items at 140°F (60°C) for 1 hour to kill hidden mites.

- Insecticidal dusts: Diatomaceous earth (food-grade) or approved acaricides applied to cracks and crevices.

- Replace nesting materials: Use disposable liners or sterilized straw.

Treatment should be repeated every 7–10 days for at least three cycles to interrupt the mite lifecycle.

Prevention Strategies for Bird Owners

Preventing mite infestations is far more effective than treating them. Key preventive measures include:

- Quarantine new birds for at least 30 days before introducing them to a flock.

- Regular inspection of skin, feathers, and enclosures—especially during warmer months.

- Maintain dry, well-ventilated housing to discourage mite proliferation.

- Encourage natural behaviors like dust bathing by providing sand or diatomaceous earth trays.

- Seal entry points to prevent wild birds or rodents from accessing coops.

- Rotate nest boxes and clean them between uses.

Mites and Wild Birds: Ecological Balance and Human Concerns

In nature, mites are part of the ecosystem and rarely cause significant harm to healthy wild bird populations. Many species coexist without severe pathology. However, during harsh winters or in urban settings with high bird density, mite loads can increase, leading to localized die-offs.

A common concern is whether bird mites can infest humans. While Dermanyssus gallinae may bite people when bird hosts are absent, they cannot establish long-term infestations on humans. These bites cause temporary itching or rash but are not known to transmit diseases to humans in North America.

If mites are found in homes, it’s usually because a nearby bird nest (e.g., in an attic or ventilation shaft) has been abandoned, prompting mites to search for new hosts. Removing the nest and sealing entry points typically resolves the issue.

Myths and Misconceptions About Bird Mites

Several myths persist about mites on birds:

- Myth: All mites are visible to the naked eye. Reality: Most are microscopic and require magnification.

- Myth: Mites mean a bird owner is unclean. Reality: Even well-maintained aviaries can experience outbreaks.

- Myth: Human scabies mites come from birds. Reality: Human scabies (Sarcoptes scabiei) is species-specific and not transmitted by birds.

- Myth: Over-the-counter insect sprays are safe for birds. Reality: Many contain chemicals lethal to birds; always consult a vet.

When to Seek Veterinary Help

Consult an avian veterinarian if your bird shows signs of distress, anemia, or persistent itching. Also seek help if home treatments fail or if mites recur after environmental cleanup. A vet can provide species-specific diagnosis and prescribe safe, effective medications.

For wild bird rehabilitators, proper biosecurity protocols—including glove use, footbaths, and isolation units—are critical to prevent cross-contamination.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What do mites on birds look like to the naked eye?

- Mites are usually too small to see clearly without magnification. They may appear as tiny moving specks—white, gray, or reddish—near the vent, eyes, or base of feathers.

- Can bird mites live on humans?

- Bird mites may bite humans if their bird host is gone, but they cannot complete their lifecycle on human blood and will die off within days.

- How do I get rid of mites in my bird’s cage?

- Clean all surfaces thoroughly, remove bedding, treat the bird with vet-approved medication, and apply avian-safe acaricides to the environment. Repeat treatment weekly for at least three weeks.

- Are mites on wild birds dangerous to pets?

- Most bird mites do not infest cats or dogs. However, close contact with heavily infested birds could lead to temporary bites, though sustained infestation is unlikely.

- Do all birds have mites?

- Not all birds have mites, but nearly all bird species can host mites under certain conditions. Low-level presence doesn’t always indicate disease—only when mites proliferate do they become problematic.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4