Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, can have devastating effects on chickens, often leading to high mortality rates within infected flocks. What does bird flu do to chickens? It attacks their respiratory, digestive, and nervous systems, causing severe illness and rapid spread in commercial and backyard poultry populations. A natural long-tail keyword variant like 'how does avian influenza affect chicken health and survival' captures the essence of this threat. The virus, particularly highly pathogenic strains such as H5N1, can result in up to 100% mortality in susceptible chicken flocks within just 48 hours of symptom onset.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Types and Strains

Avian influenza is caused by Type A influenza viruses, which are categorized based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 16 H subtypes and 9 N subtypes that commonly infect birds. Among these, H5 and H7 viruses are of greatest concern due to their potential to mutate from low pathogenic (LPAI) to highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) forms.

In chickens, LPAI may cause mild symptoms such as ruffled feathers or reduced egg production. However, when the virus evolves into HPAI—especially H5N1 or H7N9—it becomes extremely dangerous. These strains replicate rapidly in internal organs, leading to systemic infection and sudden death. Unlike wild waterfowl, which often carry the virus without showing signs, domestic chickens are highly vulnerable.

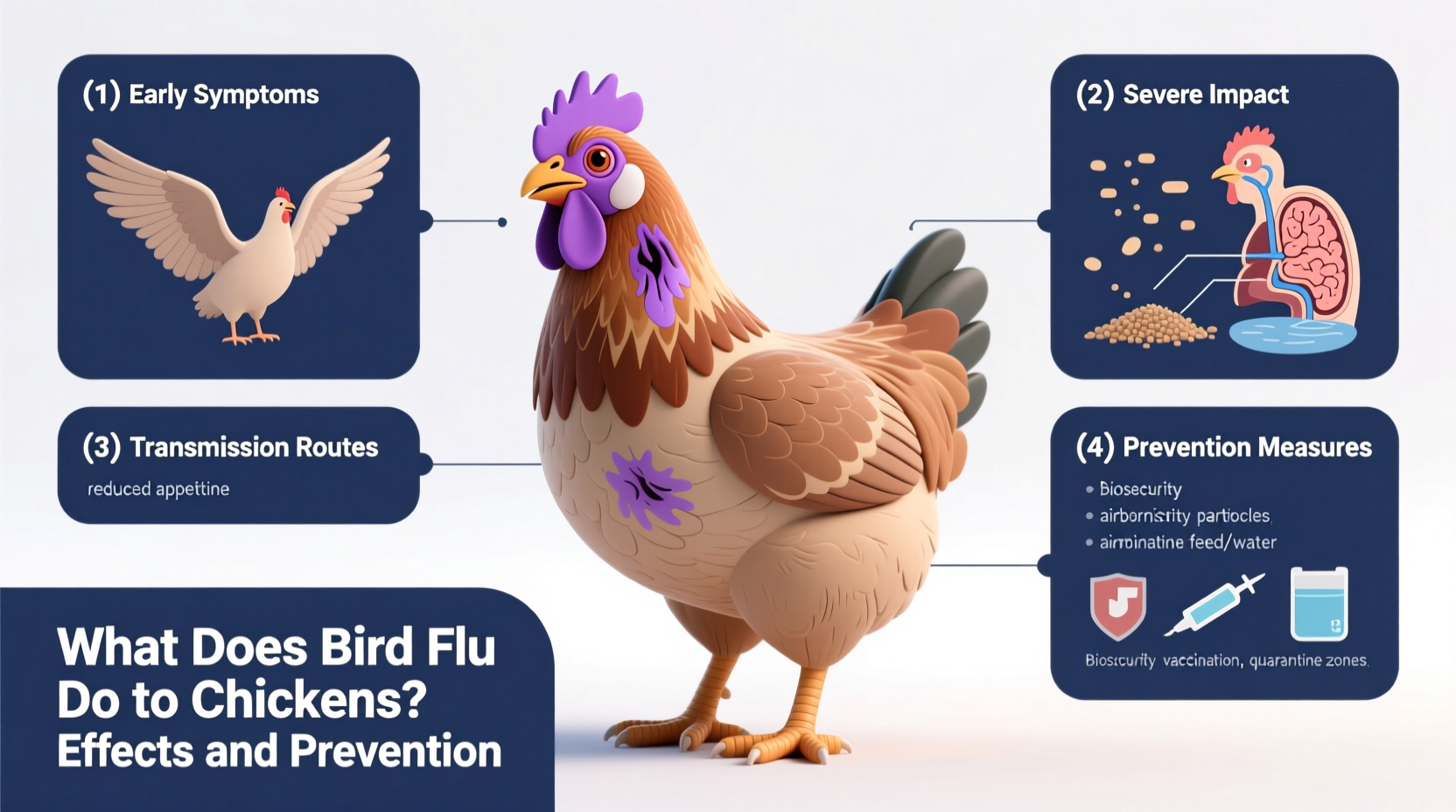

Symptoms of Bird Flu in Chickens

The clinical signs of bird flu in chickens vary depending on the strain’s pathogenicity. Low-pathogenic infections might go unnoticed or present with subtle changes:

- Mild respiratory distress (sneezing, coughing)

- Drop in egg production

- Slight decrease in appetite

- Ruffled feathers

In contrast, highly pathogenic avian influenza causes dramatic and often fatal symptoms:

- Sudden death without prior signs

- Swelling of the head, comb, and wattles

- Purple discoloration of wattles and legs

- Respiratory distress including gasping and nasal discharge

- Neurological signs such as tremors, lack of coordination, or paralysis

- Greenish diarrhea

- Blood spots in eggs or soft-shelled eggs

Infected chickens typically stop eating and drinking within hours. Mortality can reach 90–100% in unvaccinated flocks within days.

How Bird Flu Spreads Among Chickens

Transmission occurs primarily through direct contact with infected birds or indirect exposure to contaminated environments. Wild migratory birds—especially ducks, geese, and shorebirds—are natural reservoirs of avian influenza viruses. They shed the virus in feces, saliva, and nasal secretions, contaminating water sources, soil, and equipment.

Key transmission pathways include:

- Contact with wild birds or their droppings

- Contaminated feed, water, or bedding

- Farm equipment, clothing, or footwear of workers

- Airborne particles in enclosed spaces (limited but possible)

- Movement of live poultry between farms or markets

The virus can survive for weeks in cool, moist environments. Even a small amount of contaminated manure tracked into a coop on boots can introduce a lethal outbreak.

Biological Impact on Chicken Physiology

Once inside a chicken's body, the avian influenza virus binds to receptors in epithelial cells of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. From there, it replicates quickly and spreads via the bloodstream to vital organs such as the heart, liver, spleen, and brain.

Highly pathogenic strains trigger a cytokine storm—an overreaction of the immune system—that leads to widespread tissue damage and organ failure. Blood vessels become leaky, causing hemorrhaging in multiple tissues. This systemic collapse explains why affected birds die so rapidly, sometimes before obvious symptoms appear.

Egg-laying hens experience reproductive tract damage. Viral replication in ovarian and oviduct tissues disrupts egg formation, leading to misshapen shells, internal calcifications, or complete cessation of laying.

Economic and Agricultural Consequences

Bird flu outbreaks have far-reaching consequences beyond animal health. In the U.S., the 2014–2015 HPAI epidemic led to the culling of over 50 million chickens and turkeys, costing taxpayers more than $1 billion in compensation and control efforts. International trade restrictions followed, disrupting export markets for American poultry products.

Small-scale and backyard flock owners also face significant losses. Unlike large operations with biosecurity protocols, many hobby farmers lack awareness or resources to prevent introduction. An outbreak can wipe out an entire flock overnight, affecting both food security and emotional investment.

| Aspect | Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza (LPAI) | Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) |

|---|---|---|

| Mortality Rate | Low (0–20%) | Very High (up to 100%) |

| Onset of Symptoms | Gradual | Sudden, often fatal within 48 hours |

| Primary Symptoms | Reduced egg production, mild respiratory issues | Hemorrhages, swelling, neurological signs |

| Impact on Trade | Limited | Severe; triggers international bans |

| Biosecurity Response | Monitoring, quarantine | Mass culling, movement restrictions |

Prevention and Biosecurity Measures

Preventing bird flu in chickens requires strict biosecurity practices. Since no cure exists once a flock is infected, prevention is the only effective strategy. Key steps include:

- Isolate Domestic Flocks: Keep chickens away from wild birds. Use covered runs or netting to prevent contact with migrating waterfowl.

- Control Access: Limit visitors to poultry areas. Provide dedicated footwear and clothing for handlers.

- Sanitize Equipment: Regularly clean feeders, waterers, coops, and tools with disinfectants proven effective against influenza viruses (e.g., bleach solutions).

- Source Birds Carefully: Purchase chicks or adult birds only from National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP)-certified suppliers.

- Monitor Health Daily: Watch for early signs like lethargy, decreased feed intake, or abnormal droppings.

- Report Suspicious Deaths: If multiple birds die suddenly, contact your veterinarian or state animal health authority immediately.

In regions where HPAI is endemic, vaccination may be used under official supervision. However, vaccines do not always prevent infection—they may reduce shedding and slow spread but won’t eliminate the virus entirely.

Role of Government and Surveillance Programs

National agencies such as the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) monitor bird flu through surveillance programs targeting live bird markets, commercial farms, and wild bird populations. When HPAI is detected, response includes:

- Quarantine of affected premises

- Depopulation of exposed flocks

- Trace-back and trace-forward investigations

- Disinfection of facilities

- Establishment of control zones restricting poultry movement

Farmers are compensated for culled birds, but the process is disruptive and emotionally taxing. Public reporting and transparency help maintain trust and encourage compliance with containment measures.

Myths and Misconceptions About Bird Flu in Chickens

Several misconceptions persist about avian influenza and its impact:

- Myth: Cooking chicken kills the virus, so there’s no risk from eating poultry.

Fact: While true that proper cooking (165°F internal temperature) destroys the virus, the main danger lies in live bird handling and farm-level transmission, not consumption. - Myth: Only sick-looking birds spread the disease.

Fact: Infected birds can shed the virus before showing symptoms, making early detection difficult. - Myth: Backyard flocks are safe because they’re small.

Fact: Small flocks are just as susceptible and can serve as bridges between wild birds and commercial operations. - Myth: Vaccines make chickens immune.

Fact: Most vaccines reduce severity but don't block transmission completely. They are used selectively to support eradication, not replace biosecurity.

What to Do If You Suspect Bird Flu in Your Flock

If you observe sudden deaths or symptoms consistent with HPAI, take immediate action:

- Isolate the flock—do not move any birds, eggs, or equipment.

- Avoid contact with other poultry operations.

- Contact your local veterinary officer or state department of agriculture.

- Follow instructions for testing and disposal.

- Cooperate fully with officials during investigation and cleanup.

Early reporting improves containment chances and may prevent regional outbreaks. Delaying notification risks spreading the virus to neighboring farms.

Global Trends and Seasonal Patterns

Bird flu activity often follows seasonal migration patterns of wild birds. In North America, outbreaks peak in late winter and spring (February–April), coinciding with northward migrations. In Asia, where duck farming is extensive and backyard poultry common, year-round circulation occurs, especially in tropical climates.

Climate change may alter these patterns by shifting migration routes and prolonging virus survival in warmer temperatures. Increased global trade and live bird markets further complicate control efforts.

Future Outlook and Research Directions

Ongoing research focuses on developing universal avian influenza vaccines, improving rapid diagnostic tests, and enhancing surveillance using genetic sequencing. Scientists are also studying receptor differences between species to understand why some birds tolerate the virus while chickens succumb rapidly.

Public education remains critical. Outreach programs for rural communities, 4-H groups, and smallholders emphasize hygiene, reporting, and responsible flock management. Mobile apps and alert systems now provide real-time updates on outbreak locations.

FAQs About Bird Flu and Chickens

- Can humans get bird flu from chickens?

- Yes, though rare. H5N1 and H7N9 have caused human infections, usually through close contact with sick birds. Proper protective gear reduces risk.

- Is it safe to eat eggs and meat from infected chickens?

- No. Infected birds must be destroyed and not enter the food chain. Regulatory agencies enforce strict bans during outbreaks.

- How long does bird flu survive in the environment?

- The virus can persist for up to 30 days in cool, moist conditions (like manure or pond water), but only 1–2 days in hot, dry weather.

- Are all bird species equally affected?

- No. Chickens and turkeys are highly susceptible. Ducks and geese often show no symptoms but can still spread the virus.

- Can bird flu be prevented without vaccines?

- Yes. Strict biosecurity—preventing contact with wild birds and maintaining sanitation—is the most effective prevention method.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4