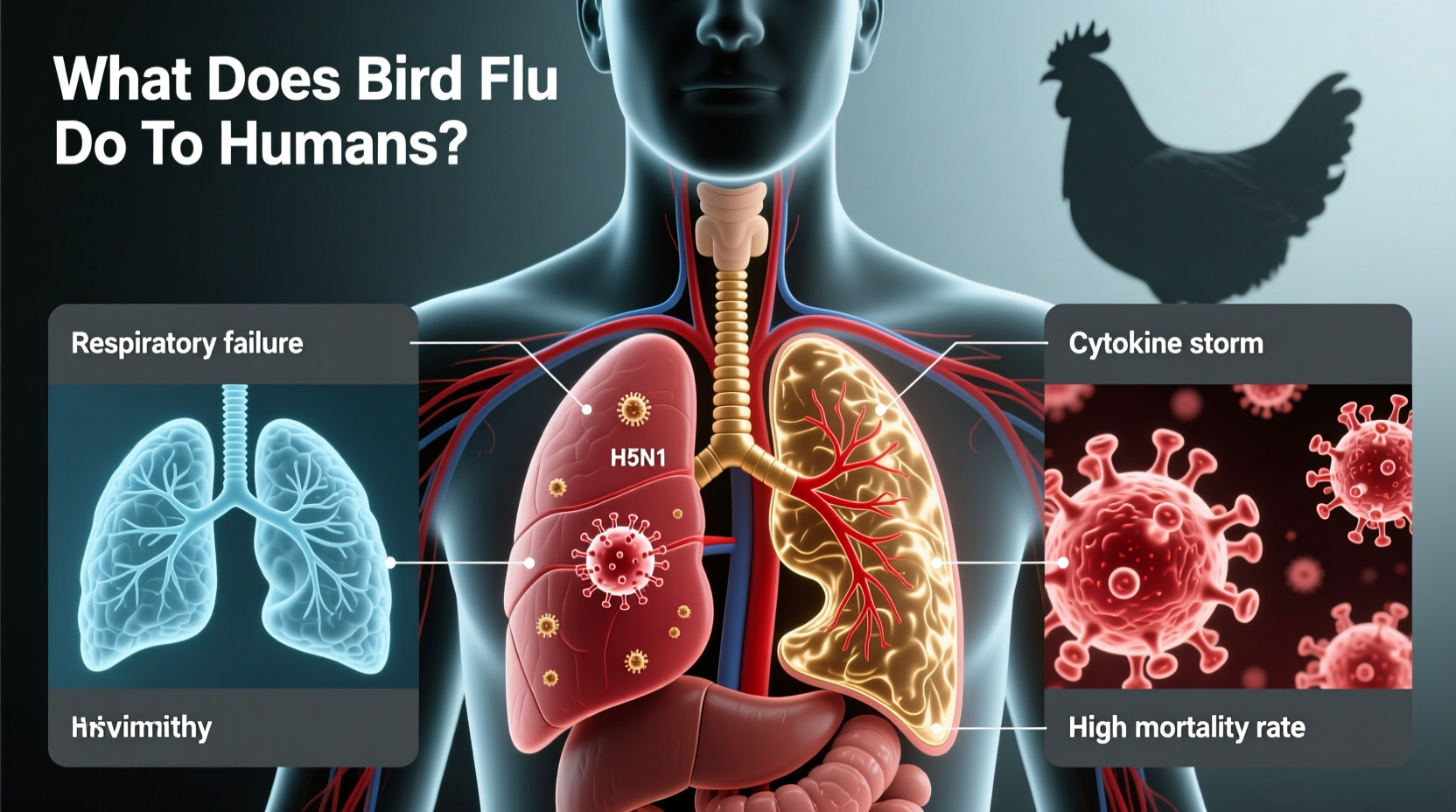

Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, can cause serious illness in humans, though transmission from birds to people remains relatively rare. The most concerning strain, H5N1, has been shown to lead to severe respiratory disease, including pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and, in some cases, death. While human-to-human transmission is limited, the potential for the virus to mutate into a more contagious form raises global public health concerns. Understanding what does bird flu do to humans is essential for early detection, prevention, and preparednessâespecially for those working with poultry or traveling to regions experiencing outbreaks.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Origins and Types

Avian influenza viruses belong to the influenza A family and are naturally found in wild aquatic birds such as ducks, geese, and swans. These birds often carry the virus without showing symptoms, serving as reservoirs that can spread it to domestic poultry like chickens and turkeys. There are numerous subtypes of avian influenza based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). Among these, H5N1, H7N9, and H5N6 are the most frequently reported to infect humans.

The first known human case of H5N1 was documented in Hong Kong in 1997. Since then, sporadic infections have occurred across Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America. Most human cases result from direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environmentsâsuch as live bird markets or farms. The virus does not easily spread between people, which has so far prevented widespread pandemics. However, scientists closely monitor these strains due to their high mortality rate when they do infect humans.

Symptoms of Bird Flu in Humans

When a person contracts bird flu, the symptoms can vary widely but often resemble those of seasonal influenzaâat least initially. Common early signs include:

- Fever (often high, above 100.4°F or 38°C)

- Cough

- Sore throat

- Muscle aches

- Headache

- Shortness of breath

However, unlike typical flu, bird flu tends to progress rapidly. Within days, patients may develop severe complications such as viral pneumonia, multi-organ failure, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Gastrointestinal symptoms like diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain have also been reported, particularly with H5N1 and H7N9 infections.

In severe cases, hospitalization is required, and antiviral medications such as oseltamivir (Tamiflu) are administered early to improve outcomes. Even with treatment, the fatality rate for H5N1 remains alarmingly highâapproximately 50% according to data from the World Health Organization (WHO).

How Is Bird Flu Transmitted to Humans?

The primary route of transmission from birds to humans involves close contact with infected poultry or contaminated surfaces. This includes:

- Handling live or dead infected birds

- Exposure to feces, saliva, or respiratory secretions

- Visiting live bird markets or backyard farms during an outbreak

- Inhaling aerosolized particles in poorly ventilated spaces where infected birds are housed

Itâs important to note that consuming properly cooked poultry or eggs does not transmit the virus. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirms that heating meat to an internal temperature of 165°F (74°C) kills the virus. However, cross-contamination during food preparationâfor example, using the same cutting board for raw chicken and vegetablesâcan pose a risk if proper hygiene isnât followed.

Human-to-human transmission remains extremely rare and typically occurs only after prolonged, unprotected contact with severely ill individuals. No sustained community spread has been documented, but researchers continue to study whether genetic mutations could enhance transmissibility.

Who Is at Higher Risk?

While anyone can theoretically contract bird flu, certain groups face increased risk due to occupational or environmental exposure:

- Poultry farmers and farm workers

- Veterinarians and animal health technicians

- Market vendors selling live birds

- Travelers visiting areas with active outbreaks

- Healthcare workers treating infected patients

People with weakened immune systems, chronic illnesses (like diabetes or heart disease), or lung conditions may experience more severe outcomes if infected. Pregnant women are also considered a vulnerable group due to changes in immune function during pregnancy.

Diagnosis and Treatment Options

Early diagnosis is crucial for effective management of bird flu in humans. If someone develops flu-like symptoms within 10 days of potential exposureâsuch as recent travel to an affected region or contact with sick birdsâa healthcare provider should be informed immediately.

Diagnostic testing typically involves collecting respiratory specimens (nasal or throat swabs) for real-time RT-PCR analysis, which can identify specific avian influenza strains. Rapid antigen tests used for seasonal flu are generally not reliable for detecting bird flu.

Treatment focuses on antiviral drugs, with oseltamivir being the first-line option. Zanamivir (Relenza) may also be effective, though it's not recommended for those with underlying respiratory diseases like asthma. Peramivir and baloxavir are additional options under investigation or use in specific cases. Treatment should begin as soon as possible, ideally within 48 hours of symptom onset, although benefits have been observed even when started later in severe cases.

| Antiviral Drug | Administration Method | Recommended Use | Potential Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) | Oral capsule or liquid | First-line treatment for H5N1 and other avian strains | Nausea, vomiting, headache |

| Zanamivir (Relenza) | Inhaled powder | Alternative for non-pregnant adults and children over 7 | Bronchospasm, coughing (avoid in asthma/COPD) |

| Peramivir (Rapivab) | Intravenous infusion | Used in hospitalized patients unable to take oral meds | Diarrhea, skin reactions |

| Baloxavir (Xofluza) | Single-dose oral tablet | Limited data; under study for avian flu | Headache, diarrhea |

Prevention and Public Health Measures

Preventing bird flu in humans requires coordinated efforts at individual, community, and international levels. Key strategies include:

- Surveillance and culling: Monitoring poultry flocks and rapidly culling infected birds helps contain outbreaks before they spread.

- Biosecurity on farms: Limiting access to poultry areas, disinfecting equipment, and wearing protective clothing reduce transmission risks.

- Personal protection: People handling birds should wear gloves, masks, goggles, and wash hands thoroughly afterward.

- Avoiding live bird markets: Travelers are advised to avoid such markets in countries experiencing outbreaks.

- Vaccination (for seasonal flu): While no widely available vaccine exists yet for H5N1 in the general population, getting a seasonal flu shot reduces the chance of co-infection, which could allow viral reassortment.

Several experimental H5N1 vaccines have been developed and stockpiled by governments for emergency use, but they are not commercially available to the public. Development continues, especially as new clades of the virus emerge.

Global Outbreak Trends and Recent Cases

In recent years, there has been a notable increase in avian influenza activity worldwide. The H5N1 strain, once primarily confined to Asia, has now spread across Europe, Africa, and the Americas. In 2022 and 2023, unprecedented numbers of wild birds and commercial poultry were affected in the U.S. and EU, prompting mass culling operations.

Human cases remain sporadic but concerning. In 2022, the United Kingdom reported its first known case of H5N1 in a person who had close contact with infected birds. In 2023, the U.S. confirmed its second human caseâalso linked to dairy cattle exposure in Texasâmarking a shift in understanding potential transmission pathways.

These developments underscore the evolving nature of the threat. As climate change alters migratory patterns and intensive farming practices expand, the interface between wild birds, domestic animals, and humans grows more complexâincreasing opportunities for zoonotic spillover.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Despite extensive research, several myths persist about avian influenza and its impact on humans:

- Myth: Eating chicken or eggs can give you bird flu.

Fact: Proper cooking destroys the virus. The risk lies in handling raw products without hygiene precautions. - Myth: Bird flu spreads easily among people.

Fact: Sustained human-to-human transmission has not occurred. Most cases stem from animal contact. \li>Myth: Thereâs nothing you can do to protect yourself.

Fact: Avoiding high-risk settings, practicing hand hygiene, and reporting suspicious bird deaths help reduce risk.

What Should You Do If You Suspect Exposure?

If youâve had close contact with sick or dead birds and begin experiencing flu-like symptoms, take immediate action:

- Isolate yourself from others to prevent potential spread.

- Contact your healthcare provider or local health department.

- Mention your exposure history clearly.

- Follow instructions for testing and quarantine.

- Do not go directly to a clinic without calling aheadâthis protects healthcare workers and other patients.

Public health authorities may recommend antiviral prophylaxis for close contacts of infected individuals, especially in high-risk settings like households or hospitals.

FAQs About What Bird Flu Does to Humans

- Can bird flu be fatal in humans?

- Yes, particularly H5N1, which has a case fatality rate of around 50%. Early treatment improves survival chances.

- Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

- Not currently available to the public. Experimental vaccines exist for emergency use but are not routinely administered.

- Can pets get bird flu and pass it to humans?

- Rarely. Cats can become infected by eating infected birds, but transmission to humans is unproven. Keep pets away from sick or dead wildlife.

- Are all bird species capable of spreading bird flu to humans?

- No. Wild waterfowl are natural carriers, but domestic poultry pose the greatest risk due to closer human contact.

- How long after exposure do symptoms appear?

- Symptoms typically appear 2â8 days after exposure, though incubation can extend up to 10 days.

Staying informed through trusted sources like the CDC, WHO, and national health departments is vital. By understanding what does bird flu do to humansâand taking sensible precautionsâwe can mitigate personal risk and support broader efforts to prevent future pandemics.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4