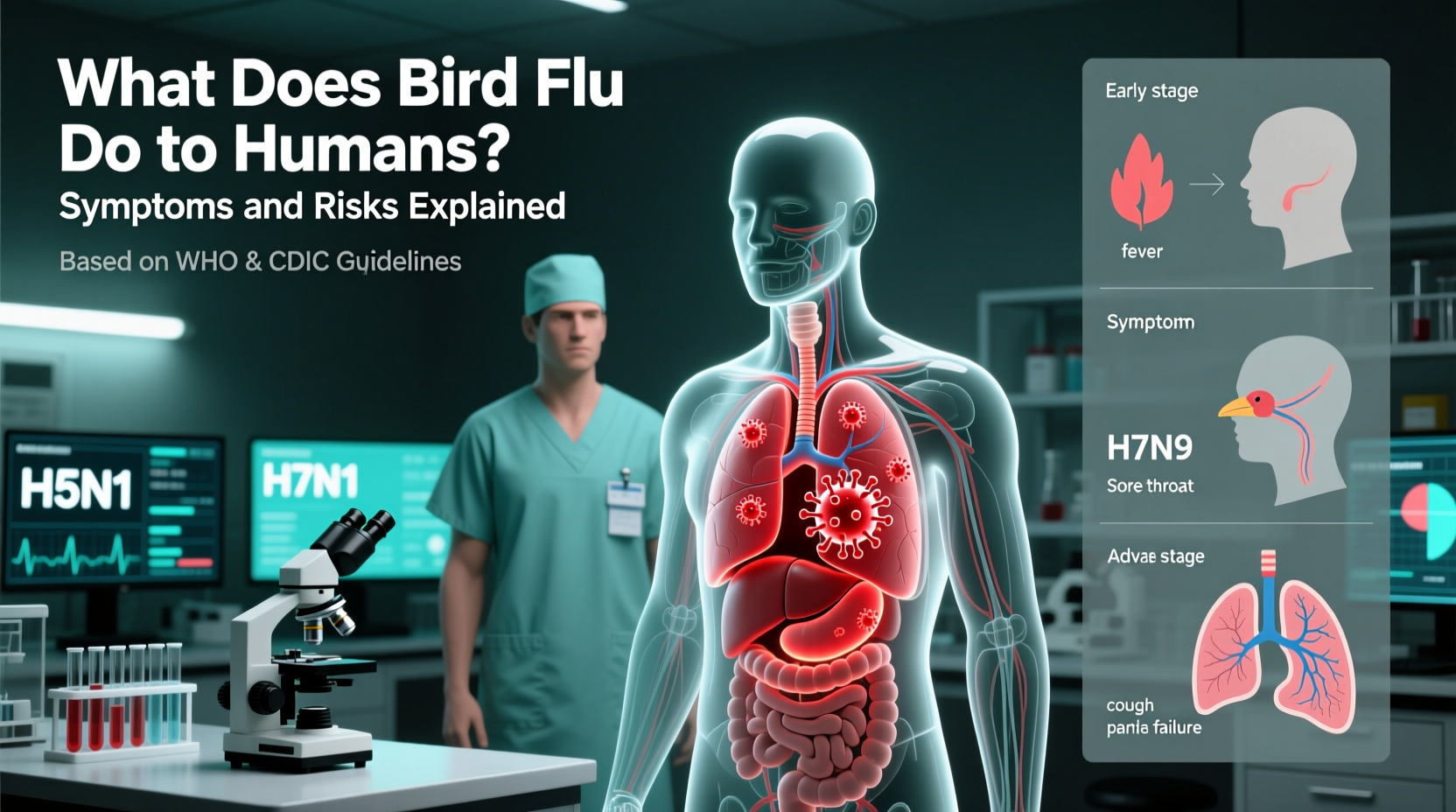

Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, can cause severe respiratory illness in humans when they come into close contact with infected birds or contaminated environments. The most concerning strain for human health is H5N1, which has demonstrated the ability to cross from birds to people, though sustained human-to-human transmission remains rare. What does the bird flu do to humans? It triggers symptoms ranging from fever and cough to pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and, in severe cases, multi-organ failure and death. Public health experts closely monitor outbreaks due to the potential for the virus to mutate into a form more easily spread among humans.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Origins and Transmission

Avian influenza viruses naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds, such as ducks and geese, which often carry the virus without showing signs of illness. These birds serve as reservoirs, shedding the virus through saliva, nasal secretions, and feces. While most strains are low-pathogenic—causing mild symptoms in poultry—certain subtypes like H5N1 and H7N9 are highly pathogenic and can lead to rapid mortality in domestic bird populations.

Human infections typically occur through direct exposure to infected live or dead birds, especially in backyard farms, live bird markets, or during slaughter and plucking. Contaminated surfaces, water sources, or airborne particles in enclosed spaces may also transmit the virus. There is currently no widespread community transmission between humans; however, sporadic cases of limited person-to-person spread have been reported, primarily among family members with prolonged, unprotected contact.

Biological Impact of Bird Flu on Humans

When a human becomes infected with avian influenza, the virus targets cells in the respiratory tract using specific receptors that differ slightly from those used by seasonal flu viruses. This difference partly explains why bird flu doesn’t spread easily among people but can be extremely aggressive once infection occurs.

Symptoms usually appear within 2 to 8 days after exposure and may include:

- Fever (often high)

- Cough

- Sore throat

- Muscle aches

- Headache

- Shortness of breath

- Conjunctivitis (in some H7 subtypes)

In severe cases, the infection progresses rapidly to lower respiratory tract disease, including viral pneumonia. The immune system's overreaction—known as a cytokine storm—can exacerbate lung damage and contribute to systemic complications affecting the heart, liver, and kidneys.

The case fatality rate for H5N1 in humans has historically been alarmingly high, exceeding 50% in confirmed cases according to the World Health Organization (WHO). However, this figure likely reflects a bias toward reporting only severe cases, as milder infections may go undetected.

Global Outbreak History and Surveillance

The first documented human case of H5N1 occurred in Hong Kong in 1997, where six out of 18 infected individuals died. A culling of all poultry in the region helped contain the outbreak. Since then, H5N1 has become endemic in several countries across Asia, Africa, and parts of Europe, particularly where biosecurity measures on farms are weak.

In 2024, new clades of H5N1—specifically the 2.3.4.4b variant—have triggered unprecedented outbreaks in wild birds and commercial poultry flocks across North America and Europe. As of early 2025, over 50 million birds have been affected in the United States alone, prompting federal agencies like the CDC and USDA to enhance surveillance at the human-animal interface.

Notably, in 2022, the first U.S. case of H5N1 in a human was identified in Colorado, linked to an outbreak in dairy cattle and poultry. The individual, a prison worker involved in culling operations, reported fatigue but recovered fully. Subsequent cases in 2024 and 2025 were similarly mild, suggesting possible changes in viral behavior or improved detection of less severe infections.

Risk Factors and Vulnerable Populations

While anyone exposed to infected birds is at risk, certain groups face higher probabilities of contracting bird flu:

- Poultry farmers and farmworkers

- Veterinarians and animal health technicians

- Market vendors handling live birds

- Hunters processing game birds

- Travelers visiting regions with active outbreaks

People with underlying conditions such as asthma, diabetes, or compromised immune systems may experience more severe outcomes if infected. Children and pregnant women are also considered potentially more vulnerable, though data remain limited due to the rarity of cases.

It’s important to note that consuming properly cooked poultry or eggs does not pose a risk of infection. The virus is destroyed at temperatures above 70°C (158°F), so standard food safety practices effectively prevent dietary transmission.

Prevention and Personal Protection Measures

For individuals working with or near birds, preventive strategies are essential. Key recommendations include:

- Wearing protective clothing: gloves, masks (N95 respirators), goggles, and disposable gowns when handling sick or dead birds.

- Practicing strict hand hygiene with soap and water or alcohol-based sanitizers after any animal contact.

- Avoiding touching eyes, nose, or mouth while working with birds.

- Reporting sick or dead birds to local wildlife or agricultural authorities instead of handling them directly.

- Vaccinating poultry flocks where available and approved by veterinary officials.

In areas experiencing outbreaks, public health agencies may advise against visiting live bird markets or participating in bird festivals. Travelers to affected regions should check advisories from the CDC or WHO before departure.

| Strain | Primary Hosts | Human Cases (Confirmed) | Fatality Rate | Geographic Spread |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H5N1 | Wild birds, poultry | ~900 (since 2003) | >50% | Asia, Africa, Europe, North America |

| H7N9 | Poultry (especially chickens) | ~1,600 (mainly China) | ~40% | China, limited export cases |

| H5N6 | Ducks, poultry | ~100 | ~60% | China, Vietnam, Japan |

| H9N2 | Backyard poultry | Rare, mild | Low | Asia, Middle East |

Diagnosis and Treatment Options

Early diagnosis is critical for managing bird flu in humans. Clinicians should consider avian influenza in patients presenting with severe respiratory illness who have had recent exposure to birds or travel to outbreak zones. Diagnostic tests include RT-PCR assays performed on respiratory specimens (nasopharyngeal swabs or tracheal aspirates).

Antiviral medications such as oseltamivir (Tamiflu), zanamivir (Relenza), and peramivir (Rapivab) are effective if administered early—ideally within 48 hours of symptom onset. These drugs inhibit viral replication and can reduce severity and duration of illness. In critically ill patients, intravenous antivirals or combination therapy may be used under medical supervision.

No widely available vaccine exists specifically for H5N1 in the general population, although candidate vaccines are stockpiled by some governments for emergency use. Seasonal flu shots do not protect against avian strains but are still recommended to reduce co-infection risks.

Public Health Response and Monitoring Systems

Agencies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) collaborate globally to track avian influenza outbreaks. Programs such as the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) monitor genetic changes in circulating strains to assess pandemic potential.

In the U.S., the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) conducts routine testing of suspect bird samples. Human cases are reported to state health departments and then to the CDC for confirmation and response coordination. Rapid sequencing allows scientists to determine whether mutations associated with mammalian adaptation—such as changes in the hemagglutinin protein—are emerging.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Despite extensive research, several myths persist about avian influenza:

- Misconception: Eating chicken or eggs can give you bird flu.

Fact: Proper cooking kills the virus. Only raw or undercooked products from infected animals pose theoretical risks. - Misconception: Bird flu spreads easily from person to person.

Fact: Sustained human-to-human transmission has not occurred. Most cases result from direct bird contact. - Misconception: All bird deaths indicate H5N1 presence.

Fact: Many diseases affect wild birds. Testing is required for confirmation. - Misconception: There’s nothing we can do to stop bird flu.

Fact: Biosecurity improvements, surveillance, and rapid culling help control outbreaks.

Future Outlook and Pandemic Preparedness

The ongoing evolution of avian influenza viruses underscores the need for vigilance. Scientists warn that if H5N1 acquires mutations enabling efficient human-to-human transmission, it could trigger a pandemic. Unlike seasonal flu, populations would have little pre-existing immunity, potentially leading to high morbidity and mortality rates.

To prepare, governments invest in surveillance, develop prototype vaccines, and update pandemic response plans. Individuals can contribute by staying informed, following public health guidance during outbreaks, and supporting responsible farming practices.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Can I get bird flu from watching birds in my backyard?

No. Observing birds from a distance poses no risk. Avoid handling sick or dead birds and wash hands after outdoor activities. - Is there a bird flu vaccine for humans?

There is no commercially available vaccine for the general public, but experimental vaccines exist for emergency deployment. - How is bird flu different from seasonal flu?

Bird flu originates in birds, affects younger age groups more severely, and has a higher fatality rate than seasonal flu, which spreads easily among people. - Should I stop feeding wild birds?

During outbreaks, local authorities may recommend pausing bird feeders to reduce congregation and disease spread. Check regional guidelines. - What should I do if I find a dead bird?

Do not touch it. Report it to your local wildlife agency or department of natural resources for safe collection and testing.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4