Birds are not mammals; they are warm-blooded vertebrates that lay eggs and belong to the class Aves, which distinguishes them from mammals that give birth to live young and nurse them with milk. This fundamental biological difference is one of many aspects that define what doing bird means in both scientific and cultural contexts. The phrase 'what doing bird' may stem from misinterpretations or phonetic renderings of queries about bird behavior, symbolism, or classification—such as 'what does it mean when a bird does this?' or 'what are birds doing during migration?' Understanding bird behavior, anatomy, and ecological roles helps clarify common misconceptions like whether birds are mammals, while also enriching our appreciation of their symbolic meanings across cultures.

Defining Birds: Biological Classification and Key Traits

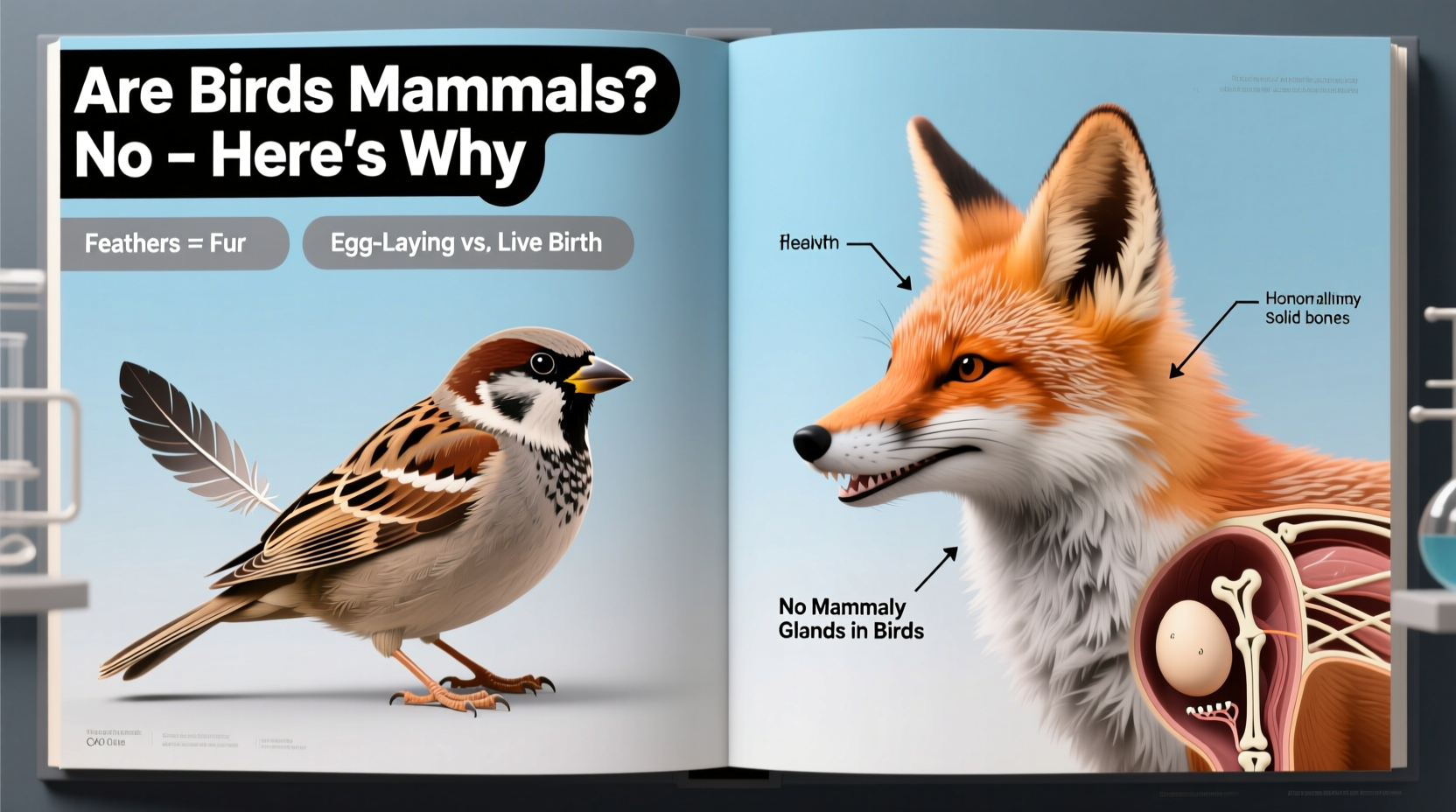

Birds are members of the animal kingdom's phylum Chordata and class Aves. Unlike mammals (class Mammalia), birds possess feathers, beaks, and hard-shelled eggs. They have lightweight skeletons adapted for flight—though not all species fly—and a highly efficient respiratory system featuring air sacs. These traits set them apart from mammals, which typically have fur or hair, external ears, and mammary glands used to feed their offspring.

One major point of confusion arises because birds and mammals are both endothermic (warm-blooded). However, this shared trait evolved independently through convergent evolution rather than indicating close relation. Genetic studies confirm that birds descended from theropod dinosaurs, making them the closest living relatives to extinct species like Tyrannosaurus rex. This evolutionary lineage further separates birds from mammals, whose ancestors diverged much earlier in Earth’s history.

Reproduction and Development: Eggs vs. Live Birth

A key distinction between birds and mammals lies in reproduction. All birds reproduce by laying amniotic eggs protected by calcified shells. Parental care varies widely—from minimal involvement in brood parasites like cuckoos to extensive nurturing seen in raptors and songbirds. In contrast, nearly all mammals give birth to live young (except monotremes such as the platypus) and nourish them with milk produced by mammary glands.

This reproductive difference plays a significant role in shaping developmental strategies. Bird chicks may be altricial (born helpless, eyes closed, requiring full parental care) or precocial (mobile shortly after hatching). Mammalian newborns, even if underdeveloped (like marsupials), remain physically attached to or near the mother for feeding and protection.

Anatomical Features That Define Avian Life

The avian body plan is uniquely adapted for energy-intensive activities like flight. Feathers—exclusive to birds—are made of keratin and serve multiple functions: insulation, display, camouflage, and aerodynamics. Wings, modified forelimbs, generate lift and thrust. Even flightless birds like ostriches and penguins retain wing structures repurposed for running or swimming.

Birds also have high metabolic rates, necessitating efficient digestion and respiration. Their hearts are large relative to body size, and most species have four-chambered hearts similar to mammals. But their lungs operate on a unidirectional airflow system supported by air sacs, allowing continuous oxygen uptake—ideal for sustained flight at high altitudes.

| Feature | Birds | Mammals |

|---|---|---|

| Skin Covering | Feathers | Fur/Hair |

| Reproduction | Egg-laying | Mostly live birth |

| Respiration | Lungs + Air Sacs | Lungs only |

| Heart Chambers | Four | Four |

| Thermoregulation | Endothermic | Endothermic |

| Young Nourishment | No milk production | Milk from mammary glands |

Cultural Symbolism of Birds Across Civilizations

Beyond biology, birds carry profound symbolic weight in human societies. In ancient Egypt, the Bennu bird—a heron-like creature—symbolized rebirth and inspired the Greek phoenix myth. Native American traditions often view eagles as messengers between humans and the divine. In Chinese culture, cranes represent longevity and wisdom, frequently depicted in art and poetry.

The act of observing bird behavior—what doing bird might colloquially imply—has long been tied to omens and spiritual insight. Ornithomancy, the practice of interpreting bird flight patterns or calls to predict events, was common in Roman and Celtic societies. Today, birdwatching combines scientific observation with personal reflection, offering both recreational enjoyment and ecological awareness.

Migration: What Are Birds Doing When They Travel Thousands of Miles?

One of the most awe-inspiring behaviors in the avian world is migration. Each year, billions of birds undertake long-distance journeys driven by seasonal changes, food availability, and breeding needs. Species like the Arctic Tern travel over 40,000 miles annually from pole to pole, while Bar-tailed Godwits make nonstop flights of more than 7,000 miles across the Pacific Ocean.

These feats rely on precise navigation using celestial cues, Earth’s magnetic field, and landscape features. Fat reserves built before departure fuel these trips, and some birds even reduce organ mass temporarily to improve efficiency. Climate change and habitat loss now threaten migratory routes, underscoring the importance of conservation efforts along flyways.

Urban Adaptation: How Birds Thrive in Human Environments

Many bird species have successfully adapted to cities and suburban areas. Pigeons, house sparrows, and starlings exploit human infrastructure for nesting and feeding. These adaptations illustrate behavioral flexibility—an essential component of what doing bird entails in modern ecosystems.

However, urban life poses risks: collisions with glass windows, exposure to pollutants, and competition with invasive species. Cities can support biodiversity through green roofs, native plant landscaping, and bird-safe building designs. Community science projects like eBird allow citizens to contribute valuable data on urban bird populations.

Conservation Challenges and Success Stories

Habitat destruction, climate change, pesticide use, and introduced predators threaten bird populations worldwide. The IUCN Red List includes over 1,400 bird species at risk of extinction. Iconic cases include the California Condor, brought back from fewer than 30 individuals through captive breeding, and the Mauritius Kestrel, saved from just four wild birds.

Effective conservation requires international cooperation. Treaties like the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (U.S.) and the African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement protect species across borders. Individuals can help by supporting protected areas, reducing plastic use, keeping cats indoors, and participating in citizen science initiatives.

Getting Started with Birdwatching: Tips and Tools

Birdwatching offers an accessible way to engage with nature and better understand what doing bird truly involves. Beginners should start with local parks or backyards, using binoculars (8x42 magnification recommended) and a regional field guide. Mobile apps like Merlin Bird ID and Audubon Guide help identify species by appearance, call, or location.

Timing matters: dawn and early morning offer peak bird activity. Dress in muted colors to avoid startling wildlife, move slowly, and keep noise low. Recording sightings in a journal or app contributes to broader ecological monitoring. Joining local birding clubs provides mentorship and group outings.

Common Misconceptions About Birds

Despite widespread fascination, several myths persist. One is that touching a baby bird will cause its parents to reject it—most birds have a poor sense of smell and recognize offspring visually or acoustically. Another myth claims hummingbirds migrate on the backs of geese; in reality, they fly solo, often crossing the Gulf of Mexico in one go.

Some believe feeding birds in summer harms them, but supplemental feeding has little impact if done responsibly. More pressing concerns include placing feeders where predators lurk or failing to clean them regularly, leading to disease spread.

Regional Variations in Bird Behavior and Observation

Bird behavior varies significantly by region due to climate, habitat, and evolutionary pressures. Tropical regions host the greatest diversity, especially in rainforests of South America and Southeast Asia. Temperate zones see dramatic seasonal shifts in species composition due to migration.

In arid regions, birds like roadrunners have adapted to extreme heat and scarce water. Polar species, such as snowy owls and ptarmigans, exhibit specialized plumage and behaviors for cold survival. Observers must tailor techniques to local conditions—using different calls, timing visits, or adjusting equipment.

FAQs: Common Questions About Bird Biology and Behavior

- Are bats birds? No, bats are mammals. Though they fly, they give live birth and nurse their young, unlike birds.

- Do all birds fly? No. Flightless birds include ostriches, emus, kiwis, and penguins, which evolved in environments without terrestrial predators.

- How do birds sing? Birds produce sound using a syrinx (a vocal organ at the base of the trachea), capable of generating complex melodies, sometimes with two independent sounds at once.

- Why do birds migrate? Migration allows birds to access abundant food and safe breeding grounds seasonally, maximizing reproductive success.

- Can birds recognize humans? Yes, some species like crows and parrots can identify individual people by face and voice, demonstrating advanced cognitive abilities.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4