The dodo bird, a flightless bird native to the island of Mauritius, went extinct in the late 17th century due to a combination of human activity and introduced species. What happened to the dodo bird is a well-documented case of human-driven extinction, with the last widely accepted sighting occurring around 1681. This tragic outcome resulted from deforestation, hunting by sailors, and predation by invasive animals such as rats, pigs, and monkeys brought to the island by European explorers. The story of what happened to the dodo bird serves as one of the earliest recorded examples of anthropogenic extinction, making it a powerful symbol in conservation biology and environmental awareness.

Historical Background of the Dodo

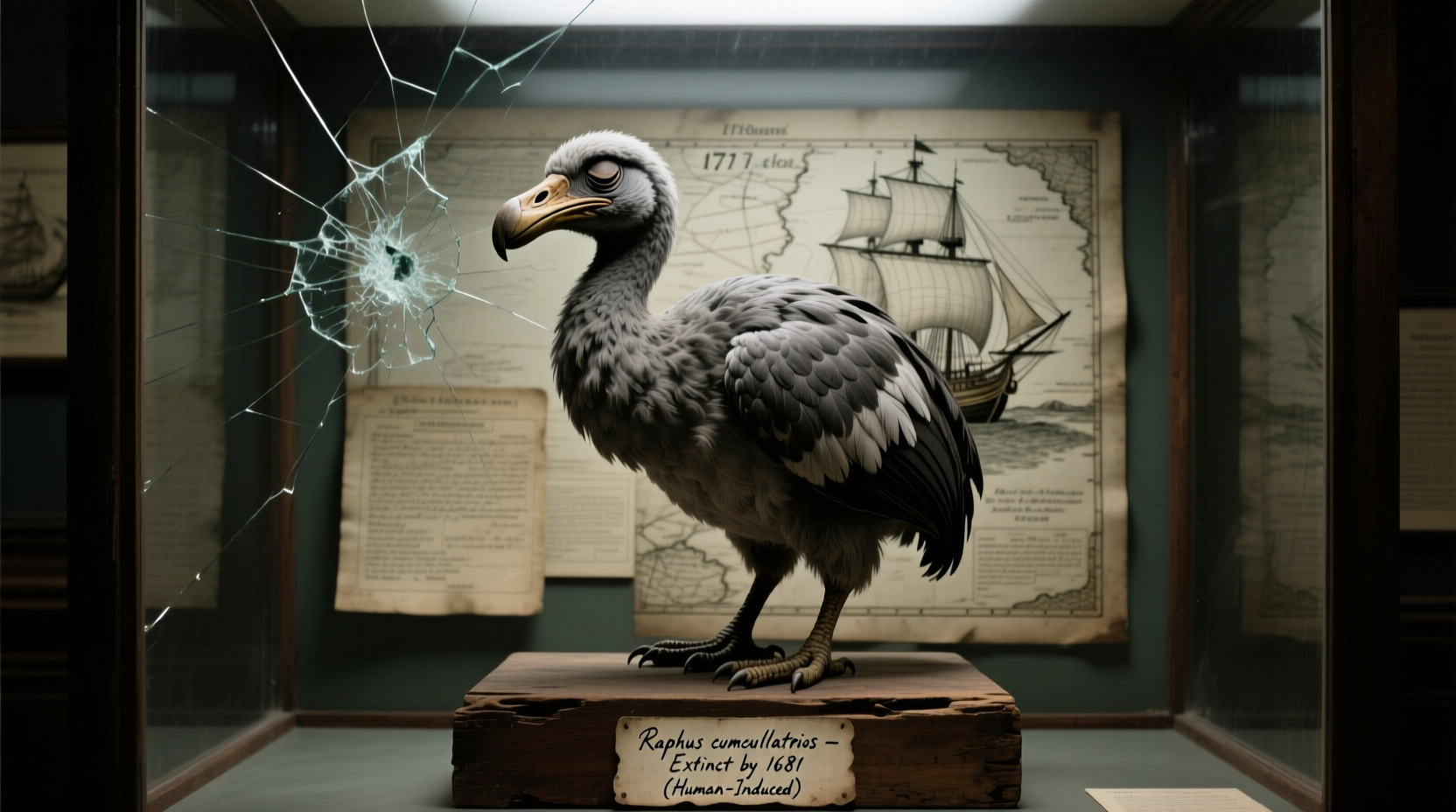

The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) was first encountered by humans in the late 16th century when Dutch sailors arrived on the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. Isolated from predators for millions of years, the dodo evolved without fear of threats, becoming flightless and ground-nesting. Its large size—up to three feet tall and weighing about 50 pounds—made it an easy target. Early accounts described the bird as clumsy and unafraid, leading to the misconception that it was unintelligent, though modern science recognizes this behavior as an adaptation to a predator-free environment.

By the time naturalists began studying the dodo more systematically in the 17th century, its population had already collapsed. No complete specimens were preserved, and much of what we know comes from sketches, written descriptions, and subfossil remains uncovered in marshlands on Mauritius. The extinction of the dodo occurred rapidly—within less than a century after human contact—making it one of the fastest documented extinctions of a vertebrate species.

Causes of the Dodo's Extinction

Several interrelated factors contributed to the disappearance of the dodo bird. Understanding what happened to the dodo bird involves examining both direct and indirect human impacts:

- Hunting by Sailors: When ships stopped at Mauritius for supplies, crew members hunted dodos for food. Although reports suggest the meat was tough and unpalatable, the birds were easy to catch and required no special tools or skills to capture.

- Habitat Destruction: As settlers established colonies, they cleared forests for agriculture and construction, destroying the dodo’s natural habitat and nesting grounds.

- Invasive Species: Animals introduced by humans—including rats, pigs, dogs, and crab-eating macaques—preyed on dodo eggs and competed for food resources. These invaders thrived in the new ecosystem, while the dodo, having evolved without defenses against predators, could not adapt quickly enough.

- Lack of Evolutionary Adaptation: Having lived in isolation for millennia, the dodo lacked genetic diversity and behavioral flexibility needed to survive sudden ecological disruption.

It's important to note that no single factor alone caused the extinction; rather, it was the cumulative effect of multiple stressors over a short period. This pattern mirrors many modern extinction events, underscoring the vulnerability of island species to external pressures.

Taxonomy and Biological Characteristics

The dodo belonged to the family Columbidae, which includes pigeons and doves. Genetic studies conducted in the early 2000s using DNA extracted from a preserved dodo specimen confirmed its close relationship to the Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica), a living species found in Southeast Asia and the Andaman Islands. This connection suggests that ancestors of the dodo likely flew to Mauritius and gradually lost their ability to fly over generations due to the absence of predators and abundant food sources on the forest floor.

Physical features of the dodo included a large, hooked beak, stout legs, small wings unsuitable for flight, and a distinctive tuft of curly feathers at the tail. While popular imagery often depicts the dodo as overweight, some scientists argue that historical illustrations may have exaggerated its size, possibly based on captive individuals fed excessive food. Recent reconstructions suggest a more athletic build suited to navigating dense undergrowth.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Raphus cucullatus |

| Family | Columbidae (pigeons and doves) |

| Native Habitat | Dense forests of Mauritius |

| Height | Approximately 3 feet (90 cm) |

| Weight | Up to 50 lbs (23 kg) |

| Flight Capability | None – flightless bird |

| Primary Causes of Extinction | Hunting, habitat loss, invasive species |

| Last Confirmed Sighting | c. 1681 |

Cultural Significance and Symbolism

Although the dodo disappeared centuries ago, its image endures in literature, language, and popular culture. The phrase "dead as a dodo" has entered common usage to describe something obsolete or extinct. In Lewis Carroll’s *Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland* (1865), the Dodo character participates in the famous Caucus Race, contributing to the bird’s whimsical and somewhat bumbling public persona.

Beyond fiction, the dodo has become a global icon for extinction and environmental fragility. Conservation organizations use its image to raise awareness about biodiversity loss and the consequences of human negligence. Ironically, despite being labeled foolish in folklore, the dodo’s real-life story highlights not stupidity but ecological innocence—an animal perfectly adapted to a stable environment undone by sudden change.

Modern Scientific Interest and Rediscovery Efforts

In recent decades, renewed scientific interest in the dodo has led to significant discoveries. Paleontologists have excavated numerous subfossil bones from swamp deposits in Mauritius, allowing for detailed anatomical analysis. CT scans and 3D modeling have helped reconstruct how the bird moved, fed, and interacted with its environment.

Some researchers have even explored the possibility of de-extinction using advanced genetic techniques. While still speculative, efforts to sequence the full dodo genome could one day enable scientists to insert key genes into closely related species like the Nicobar pigeon, potentially reviving certain traits of the original bird. However, ethical and ecological concerns remain substantial, including questions about habitat suitability and the purpose of reintroducing a species into a changed world.

Lessons from the Dodo for Contemporary Conservation

Understanding what happened to the dodo bird offers critical lessons for protecting endangered species today. Island ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to invasive species and habitat alteration. Many current conservation strategies—such as biosecurity measures, eradication of non-native predators, and reforestation programs—were informed by historical cases like the dodo’s extinction.

For example, ongoing efforts to protect the critically endangered kakapo in New Zealand mirror interventions that might have saved the dodo: relocating individuals to predator-free islands, intensive monitoring, and breeding programs. The dodo’s fate reminds us that even seemingly abundant species can vanish quickly if left unprotected.

Common Misconceptions About the Dodo

Despite widespread recognition, several myths persist about the dodo bird:

- Myth: The dodo was stupid. Reality: Its lack of fear was an evolutionary adaptation, not cognitive deficiency.

- Myth: It went extinct because it couldn’t adapt. Reality: It didn’t have time to adapt—the changes were too rapid and extreme.

- Myth: We have complete skeletons. Reality: Most skeletal material is fragmented; no complete mounted skeleton exists from a single individual.

- Myth: It was fat and lazy. Reality: Artistic depictions may reflect overfed captives; wild dodos were likely leaner and more active.

How to Learn More and Support Bird Conservation

While the dodo itself cannot be revived, its legacy lives on through education and conservation action. Those interested in avian biology and extinction prevention can:

- Visit natural history museums featuring dodo exhibits, such as the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, which houses the only known soft tissue remains (a dried head and foot).

- Support organizations like BirdLife International, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), or the Audubon Society that work to protect threatened bird species.

- Participate in citizen science projects like eBird or the Christmas Bird Count to contribute data on bird populations.

- Advocate for policies that prevent habitat destruction and regulate invasive species.

Additionally, learning about local bird species and practicing responsible ecotourism helps promote broader awareness of biodiversity challenges. Every effort counts toward preventing future tragedies like what happened to the dodo bird.

Frequently Asked Questions

- When did the dodo bird go extinct?

- The dodo bird is believed to have gone extinct around 1681, with the last confirmed sighting recorded during that time.

- Why couldn't the dodo fly?

- The dodo evolved on an island with no natural predators and abundant food, so flying became unnecessary. Over generations, its wings reduced in size and strength, resulting in flightlessness.

- Could the dodo be brought back to life?

- While theoretical research into de-extinction exists, there are no current plans to resurrect the dodo. Challenges include incomplete DNA samples and suitable habitats.

- Is the dodo related to dinosaurs?

- No, the dodo is not a dinosaur. However, like all birds, it shares a common ancestor with theropod dinosaurs. Biologically, it is a type of pigeon.

- Where can I see a real dodo specimen?

- The most complete remains are housed at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, including a preserved head and foot. Other museums display replicas or partial skeletons.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4