A bird mite is a tiny parasitic arachnid that feeds on the blood or skin of birds, commonly affecting poultry, wild birds, and pet birds. Also known as avian mites, these microscopic pests—such as Dermanyssus gallinae (the red poultry mite) and Ornithonyssus sylviarum (northern fowl mite)—are most active at night and can survive off-host for several weeks. Understanding what is a bird mite involves recognizing its life cycle, host preferences, and potential impact on both avian health and human environments. A common longtail keyword variant like 'what kind of pest is a bird mite and how does it spread in homes' reflects growing concern among homeowners and bird enthusiasts about unexpected infestations after nesting birds leave eaves or attics.

Biological Classification and Life Cycle of Bird Mites

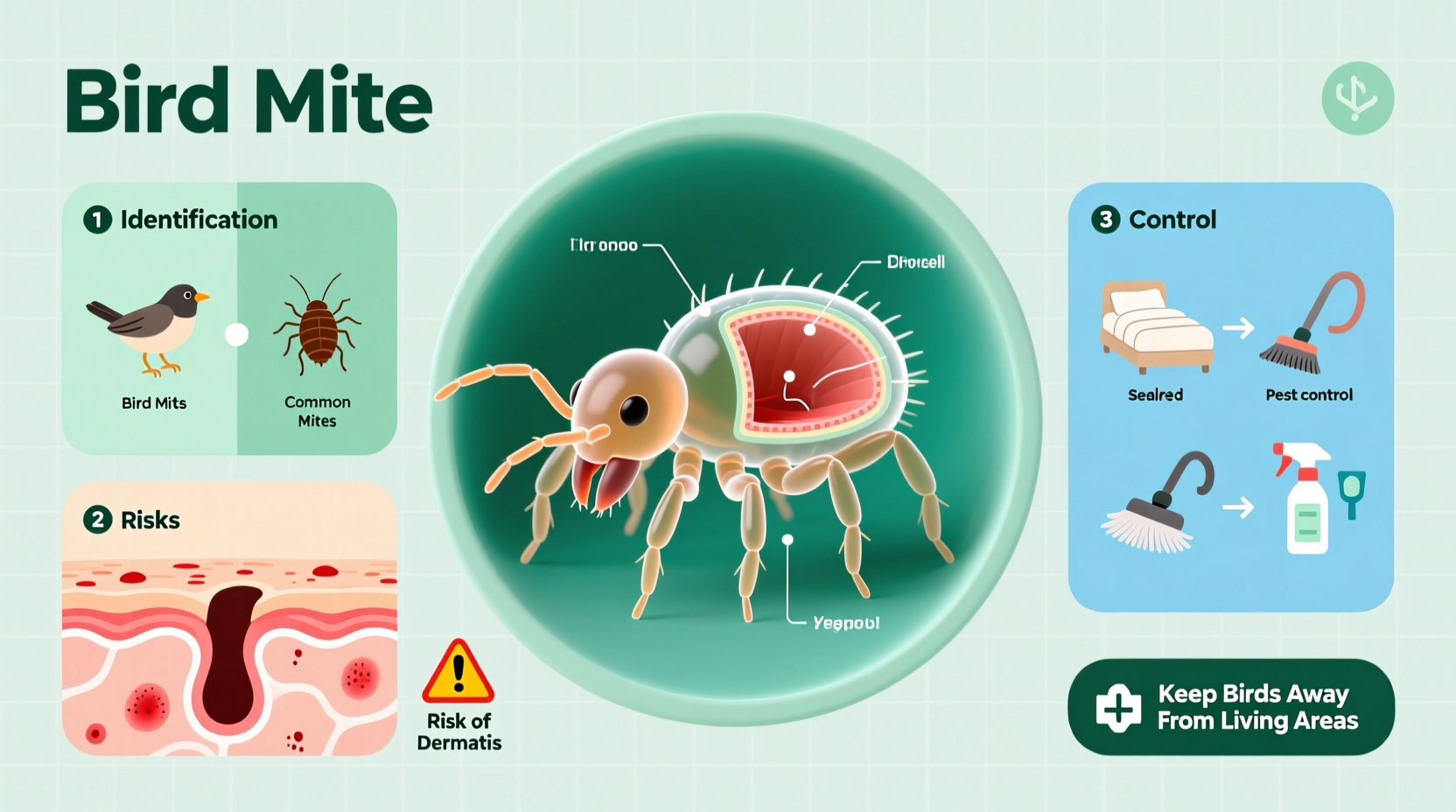

Bird mites belong to the class Arachnida, making them relatives of spiders and ticks rather than insects. They have eight legs in their adult stage and undergo a life cycle consisting of egg, larva, protonymph, deutonymph, and adult stages. This entire process can be completed in as little as seven days under optimal conditions—temperatures between 70–85°F (21–29°C) and high humidity.

The red poultry mite (Dermanyssus gallinae) is particularly notorious due to its ability to hide in cracks and crevices during the day and emerge at night to feed. Unlike some other mites, it does not live permanently on the host but instead visits to feed intermittently. In contrast, the northern fowl mite (Ornithonyssus sylviarum) spends its entire life on the bird, leading to more severe dermatological issues if left untreated.

Common Hosts and Transmission Pathways

Bird mites primarily infest birds such as chickens, pigeons, sparrows, starlings, and parrots. However, when their natural hosts abandon nests—especially common in spring and early summer—these mites may enter homes seeking new hosts. This often occurs when bird nests located near windows, vents, or attics are vacated.

Transmission to indoor environments typically happens through small openings: gaps around windows, ventilation systems, or roofline access points. Once inside, they may bite humans, causing irritation, though they cannot reproduce on human blood. The question 'can bird mites live on humans?' is frequently searched; while temporary bites occur, sustained infestation is biologically unlikely because bird mites require avian physiology to complete their reproductive cycle.

Symptoms and Signs of Infestation

Identifying a bird mite problem early is crucial. In birds, signs include restlessness, feather loss, skin lesions, reduced egg production, and anemia in severe cases. Observing birds constantly preening or appearing agitated may indicate mite presence.

In homes, people may experience small, red, itchy bumps—often mistaken for bed bug bites. These are usually concentrated on exposed skin areas like arms, neck, and face. Because bird mites are nearly invisible to the naked eye (measuring 0.5–1 mm), confirmation often requires professional inspection or microscopic analysis.

Another clue is increased activity at night. Since many bird mites are nocturnal feeders, individuals reporting nighttime itching with no visible insects should consider recent bird activity near the home as a possible cause.

Health Implications for Birds and Humans

For birds, chronic mite infestations lead to stress, weakened immune systems, and secondary infections. In commercial poultry operations, this translates into economic losses from decreased productivity and higher mortality rates.

While bird mites are not known to transmit diseases to humans in the U.S., they can act as mechanical vectors for pathogens such as Salmonella and E. coli in poultry settings. Human reactions vary: some experience mild itching, while others develop hypersensitivity responses resembling allergic dermatitis. It's important to note that although uncomfortable, these mites do not burrow into human skin like scabies mites.

Prevention Strategies for Homes and Aviaries

Preventing bird mite infestations starts with managing bird access to residential structures. Sealing entry points, installing mesh screens over vents, and removing abandoned nests promptly are essential steps. If you maintain backyard chickens or aviaries, regular coop inspections and cleaning are critical.

- Clean coops weekly: Remove droppings, replace bedding, and disinfect surfaces with steam or approved acaricides.

- Inspect nesting materials: Use diatomaceous earth (food-grade) in nesting boxes to deter mites naturally.

- Monitor wild bird nests: Avoid disturbing active nests (due to legal protections), but schedule removal within 1–2 weeks after fledging season ends.

- Install exclusion devices: Use humane deterrents like slope guards or netting to prevent pigeons or sparrows from nesting on ledges.

Effective Treatment Options

Once an infestation is suspected, targeted intervention is necessary. For birds, veterinarians may recommend topical treatments such as ivermectin or permethrin-based sprays formulated specifically for avian use. Never apply dog or cat flea products to birds—they can be fatal.

For indoor environments, integrated pest management (IPM) approaches work best:

- Vacuum thoroughly: Use a HEPA-filter vacuum on carpets, baseboards, furniture, and window frames. Dispose of the vacuum bag immediately in a sealed outdoor container.

- Wash linens and clothing: Launder all bedding, curtains, and clothes in hot water (>130°F) and dry on high heat for at least 30 minutes.

- Apply residual insecticides: Licensed pest control professionals may use pyrethroid-based sprays in wall voids and hiding spots. Over-the-counter foggers are generally ineffective against hidden mite populations.

- Use desiccants: Products containing silica aerogel or diatomaceous earth can dehydrate mites in inaccessible areas.

It’s worth noting that DIY remedies like essential oils lack consistent scientific backing and may irritate sensitive individuals or pets. Always consult a licensed exterminator before widespread chemical application.

Regional Differences and Seasonal Patterns

Bird mite activity varies by climate. In temperate regions like the northeastern United States, peak infestations occur in late spring and summer, coinciding with bird breeding seasons. Warmer southern states may see year-round activity, especially in urban areas with large pigeon populations.

Urban dwellers in cities like New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles report higher incidents due to dense bird populations nesting on buildings. Meanwhile, rural poultry farmers face recurring challenges with red mites in coops, necessitating routine monitoring programs.

Seasonal migration patterns also influence risk. As migratory birds pass through regions, temporary nesting increases local mite pressure. Homeowners should remain vigilant during March–June and September–October, depending on location.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Mites

Several myths persist about bird mites, complicating proper identification and response:

- Misconception 1: “Bird mites can infest humans long-term.” Reality: While bites occur, reproduction requires avian hosts.

- Misconception 2: “They only affect dirty homes.” Reality: Cleanliness doesn’t prevent mites from entering via external bird sources.

- Misconception 3: “Over-the-counter lice shampoos kill bird mites.” Reality: These products are ineffective against environmental mite populations.

- Misconception 4: “All crawling mites in homes are bird mites.” Reality: Dust mites, spider mites, and other species exist but don’t bite humans.

When to Call a Professional

If self-treatment fails after two weeks, or if multiple household members report persistent bites despite cleaning, professional help is advised. Pest control experts can conduct thorough inspections using magnification tools and adhesive traps to confirm mite presence.

Veterinarians specializing in avian care should be consulted for pet birds showing signs of distress. Blood tests or skin scrapings may be needed to rule out other conditions like fungal infections or nutritional deficiencies.

| Mite Species | Primary Host | Feeding Behavior | Survival Off-Host | Treatment Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dermanyssus gallinae | Chickens, pigeons | Night feeder, hides in cracks | Up to 9 months | Coop disinfection, acaricides |

| Ornithonyssus sylviarum | Chickens, wild songbirds | Permanent ectoparasite | ~2 weeks | Topical ivermectin, coop cleaning |

| Sternostoma tracheacolum | Canaries, finches | Respiratory tract mite | Lives internally | Veterinary diagnosis required |

How to Verify a Bird Mite Infestation

Because symptoms overlap with other skin conditions or pests, verification is key. Steps include:

- Place double-sided tape near suspected areas overnight; check for trapped mites under a microscope.

- Collect samples in a sealed plastic bag and submit to a university extension lab or entomologist for identification.

- Document timing and location of bites in relation to bird sightings or nest removal.

- Rule out alternative causes such as bed bugs, fleas, or dermatitis through medical or pest professional evaluation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- Can bird mites live in your hair?

- No, bird mites do not infest human hair. They may crawl on the scalp if searching for a host but cannot establish colonies there.

- How long do bird mite bites last?

- Bite reactions typically resolve within 1–2 weeks. Antihistamines or hydrocortisone cream can reduce itching.

- Do bird mites go away on their own?

- Possibly, if the source (e.g., abandoned nest) is removed and no new hosts appear. However, they can survive months without feeding, so proactive treatment is recommended.

- Are bird mites the same as scabies?

- No. Scabies mites (Sarcoptes scabiei) burrow into human skin and reproduce there. Bird mites only bite superficially and cannot complete their life cycle on humans.

- Can I get bird mites from my pet bird?

- Yes, especially if the bird is infested or has been exposed to wild birds. Regular veterinary checkups and quarantine of new birds help prevent transmission.

Understanding what is a bird mite goes beyond simple definition—it involves awareness of ecological relationships, seasonal behaviors, and practical mitigation strategies. Whether you're a backyard chicken keeper, a city dweller dealing with pigeon nests, or a concerned homeowner noticing mysterious bites, recognizing the signs and acting swiftly ensures both avian welfare and human comfort. By combining biological knowledge with actionable prevention techniques, individuals can effectively manage and eliminate bird mite risks in any environment.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4