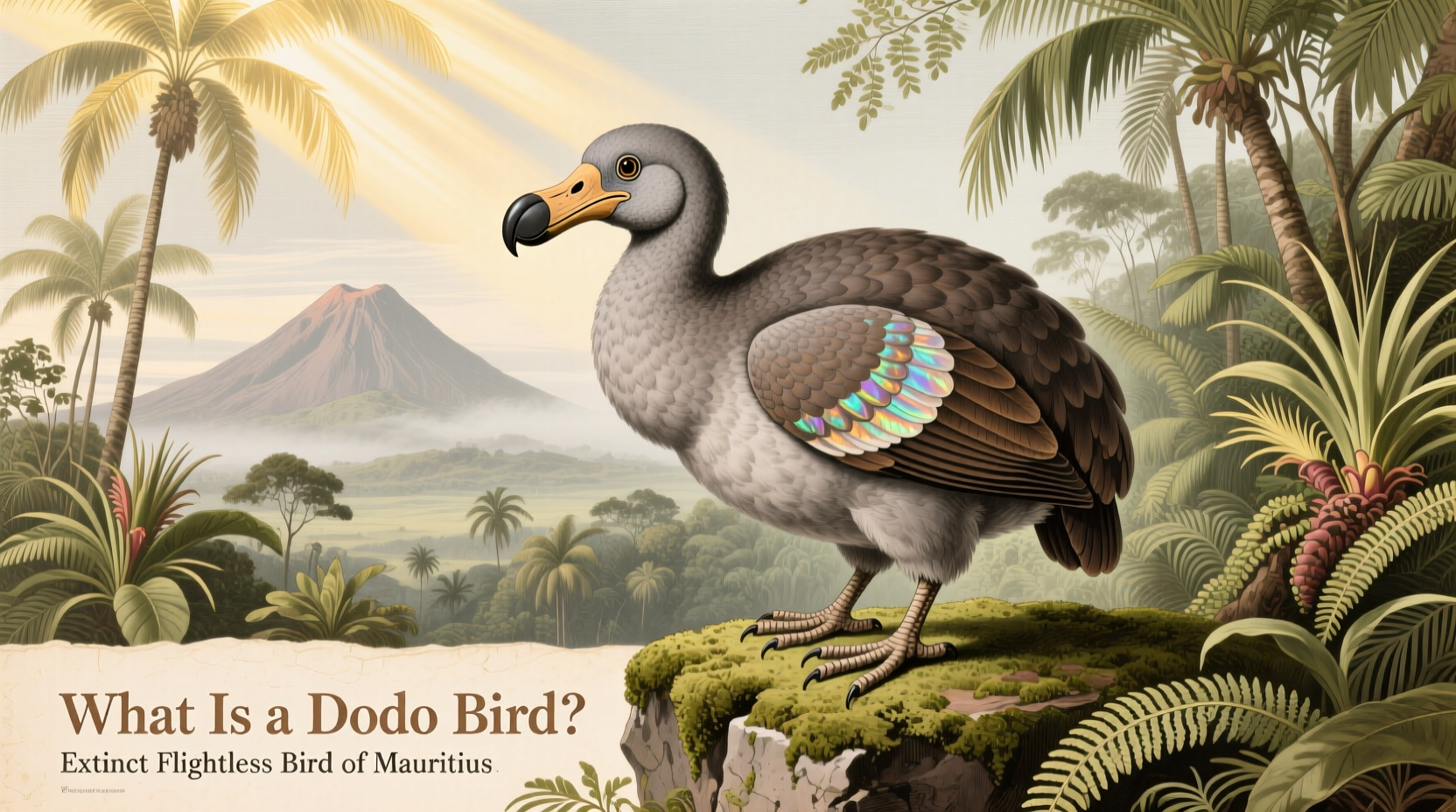

A dodo bird is an extinct flightless bird that once lived on the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. Scientifically known as Raphus cucullatus, the dodo is one of the most famous examples of human-driven extinction in natural history. Often used in phrases like 'dead as a dodo,' this unique bird has become a powerful symbol of ecological loss and human impact on fragile island ecosystems. Understanding what is a dodo bird involves exploring not only its physical characteristics and habitat but also its historical significance, biological classification, and enduring legacy in culture and conservation science.

Historical Discovery and Timeline

The dodo bird was first encountered by humans in the late 16th century, specifically around 1598, when Dutch sailors landed on the previously uninhabited island of Mauritius. These seafarers described the bird as large, clumsy, and unafraid of people—traits that made it easy prey. Unlike birds from continents with predators, the dodo had evolved without natural threats, leading to its tameness and inability to fly. This lack of fear contributed significantly to its rapid decline.

Within less than a century of its discovery, the dodo went extinct. The last widely accepted sighting of a live dodo occurred around 1662, though some reports suggest individuals may have survived into the 1680s. By the early 18th century, the species was gone. Its swift disappearance shocked later naturalists and played a pivotal role in shaping modern understandings of extinction.

Biological Characteristics and Classification

The dodo belonged to the order Columbiformes, making it a close relative of pigeons and doves. Despite its bulky appearance, genetic studies conducted in the 2000s confirmed that the dodo shared a common ancestor with the Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica), supporting its placement within the Columbidae family.

Adult dodos stood about three feet (90 cm) tall and weighed between 20 to 30 pounds (9–14 kg). They had grayish plumage, a large hooked beak, short wings incapable of flight, and stout yellow legs. Their skulls were disproportionately large, housing a strong jaw adapted for crushing hard fruits and seeds. The bird’s sternum lacked the keel structure necessary for anchoring flight muscles—a key anatomical feature confirming its flightless nature.

Due to limited fossil and specimen records, much of our understanding comes from subfossil remains found in marshlands on Mauritius, particularly at the Mare aux Songes site. These bones, combined with early illustrations and sailor journals, help reconstruct the dodo’s biology.

Habitat and Ecology

Mauritius, a volcanic island located about 560 miles (900 km) east of Madagascar, provided an isolated environment where the dodo evolved over thousands of years. With no native land mammals or significant predators, the ecosystem allowed birds like the dodo to occupy niches typically filled by mammals elsewhere.

The dodo likely inhabited lowland forests and wetlands, feeding primarily on fallen fruits, nuts, seeds, and possibly roots and small invertebrates. Some researchers speculate that it played a vital seed-dispersal role, particularly for the now-endangered Tambalacoque tree, although this mutualistic relationship remains debated.

Its reproductive strategy appears to have been slow, with evidence suggesting it laid just one egg per clutch. This low reproductive rate made recovery from population declines nearly impossible once pressures increased.

Causes of Extinction

The extinction of the dodo was not caused by a single factor but rather a cascade of interrelated human-driven changes. Key contributors include:

- Hunting by Sailors: Early European visitors hunted dodos for food, despite accounts describing the meat as tough and unpalatable.

- Introduction of Invasive Species: Rats, pigs, monkeys, and cats brought accidentally or intentionally to Mauritius preyed on dodo eggs and competed for food resources.

- Habitat Destruction: As settlers cleared forests for agriculture and settlements, the dodo’s natural habitat shrank dramatically.

- Lack of Evolutionary Adaptation: Having evolved in isolation, the dodo had no defenses against fast-moving predators or sudden environmental change.

These factors combined created what ecologists call an 'extinction vortex'—a downward spiral from which the species could not recover.

Cultural Symbolism and Legacy

Though physically gone, the dodo endures as a cultural icon. It has appeared in literature, art, and popular media for centuries. One of the most notable appearances is in Lewis Carroll’s Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), where the Dodo character organizes a 'Caucus Race.' While Carroll’s portrayal is whimsical, it helped cement the bird in public imagination.

In modern times, the phrase 'dead as a dodo' is commonly used to describe something obsolete or outdated. However, this metaphor often oversimplifies the bird’s story. Rather than being inherently flawed or 'doomed,' the dodo was a highly specialized creature perfectly adapted to its environment—until that environment changed too rapidly due to human activity.

Today, the dodo serves as a cautionary tale in environmental education and conservation movements. It symbolizes the fragility of island biodiversity and the irreversible consequences of neglecting ecological stewardship.

Scientific Rediscovery and Research

For many years, the dodo was poorly understood, partly because no complete specimens survived. The most famous soft-tissue remains—the Oxford Dodo—consist of a head and foot preserved at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. This specimen, derived from a bird kept in Europe in the 17th century, has been crucial for DNA analysis.

In the 2000s, advances in ancient DNA sequencing allowed scientists to extract genetic material from the Oxford Dodo’s remains. These studies confirmed its evolutionary lineage and clarified misconceptions about its size and behavior. For example, earlier depictions showed the dodo as extremely fat, but more accurate reconstructions based on bone structure suggest a more athletic build suited to seasonal fat storage.

Ongoing paleontological work in Mauritius continues to uncover new fossils, offering insights into the dodo’s life cycle, diet, and interactions with other extinct species such as the giant tortoise and the flightless red rail.

Where to See Dodo Remains and Replicas

While no living dodos exist, several museums house original bones, casts, and artistic reconstructions. Notable locations include:

- Oxford University Museum of Natural History (UK): Home to the only known soft-tissue remains.

- Natural History Museum, London: Displays a complete skeletal mount based on subfossil evidence.

- Museum of Zoology, Cambridge: Holds dodo bones and historical texts.

- Natural History Museum at Tring (UK): Features a lifelike model in its avian evolution exhibit.

- Museums in Mauritius: Local institutions showcase regional fossils and educational exhibits about island extinction.

Many of these institutions also offer virtual tours and online databases, allowing global access to dodo research materials.

Common Misconceptions About the Dodo

Several myths persist about the dodo bird, often distorting its true nature:

- Myth: The dodo was stupid. Reality: Its brain-to-body ratio was typical for a bird of its size and family. Its lack of fear was not stupidity but evolutionary adaptation.

- Myth: The dodo went extinct solely due to overhunting. Reality: While hunting played a role, invasive species and habitat loss were equally—if not more—important.

- Myth: We have full skeletons of dodos. Reality: No complete skeleton exists; reconstructions are based on multiple partial specimens.

- Myth: The dodo was overweight. Modern analyses suggest earlier illustrations exaggerated its girth, possibly due to captive feeding or artistic license.

| Feature | Dodo Bird Traits |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Raphus cucullatus |

| Height | Approx. 3 ft (90 cm) |

| Weight | 20–30 lbs (9–14 kg) |

| Wings | Small, flightless |

| Diet | Fruits, seeds, nuts, possibly roots |

| Lifespan (estimated) | Up to 20 years |

| Extinction Date | Mid-to-late 17th century |

| Native Habitat | Forests of Mauritius, Indian Ocean |

Lessons for Modern Conservation

The story of the dodo offers critical lessons for today’s conservation efforts. Islands continue to harbor high levels of endemic species vulnerable to invasive predators and habitat disruption. Examples include the Hawaiian honeycreepers, New Zealand’s kakapo, and the Galápagos penguin—all facing threats similar to those that doomed the dodo.

Modern strategies such as predator-free sanctuaries, biosecurity protocols, and rewilding projects draw inspiration from historical extinctions. The dodo reminds us that even seemingly abundant species can vanish quickly if their ecosystems are destabilized.

Moreover, the growing field of de-extinction—using genetic engineering to revive lost species—has sparked debate about whether the dodo could one day be 'resurrected.' While technically challenging, such discussions underscore the bird’s lasting scientific and ethical relevance.

Frequently Asked Questions

- When did the dodo bird go extinct?

- The dodo bird is believed to have gone extinct by the late 17th century, with the last confirmed sighting around 1662. Some unverified reports extend to the 1680s.

- Why can't dodo birds fly?

- Dodo birds evolved without predators on Mauritius, so flight became unnecessary. Over time, their wings reduced in size and their bodies grew heavier, making flight impossible.

- Is the dodo related to dinosaurs?

- No, the dodo is not a dinosaur. However, like all birds, it shares a distant evolutionary ancestry with theropod dinosaurs. It is more closely related to pigeons than to any prehistoric reptile.

- Can scientists bring the dodo back?

- Currently, no. While advances in genetics make de-extinction theoretically possible, the dodo’s degraded DNA and complex developmental requirements present major obstacles. Full resurrection remains speculative.

- Was the dodo really dumb?

- No. The idea that the dodo was unintelligent stems from its lack of fear toward humans. In reality, it was well-adapted to its environment; its behaviors were appropriate for an island with no predators.

In conclusion, what is a dodo bird extends far beyond a simple definition. It represents a convergence of biology, history, and human responsibility. Once a thriving inhabitant of Mauritius, the dodo now stands as both a scientific subject and a moral symbol—a reminder of how swiftly life can disappear when nature is taken for granted.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4