What is molt in birds? Molt refers to the natural process by which birds systematically shed and replace their feathers. This essential biological cycle ensures that birds maintain optimal flight performance, insulation, and appearance throughout their lives. Understanding what is molt in birds reveals not only the physiological demands of avian life but also offers critical insights for birdwatchers tracking seasonal changes in plumage. Molting is not a one-time event but a recurring, energy-intensive process influenced by age, species, environment, and reproductive cycles.

The Biology Behind Bird Molting

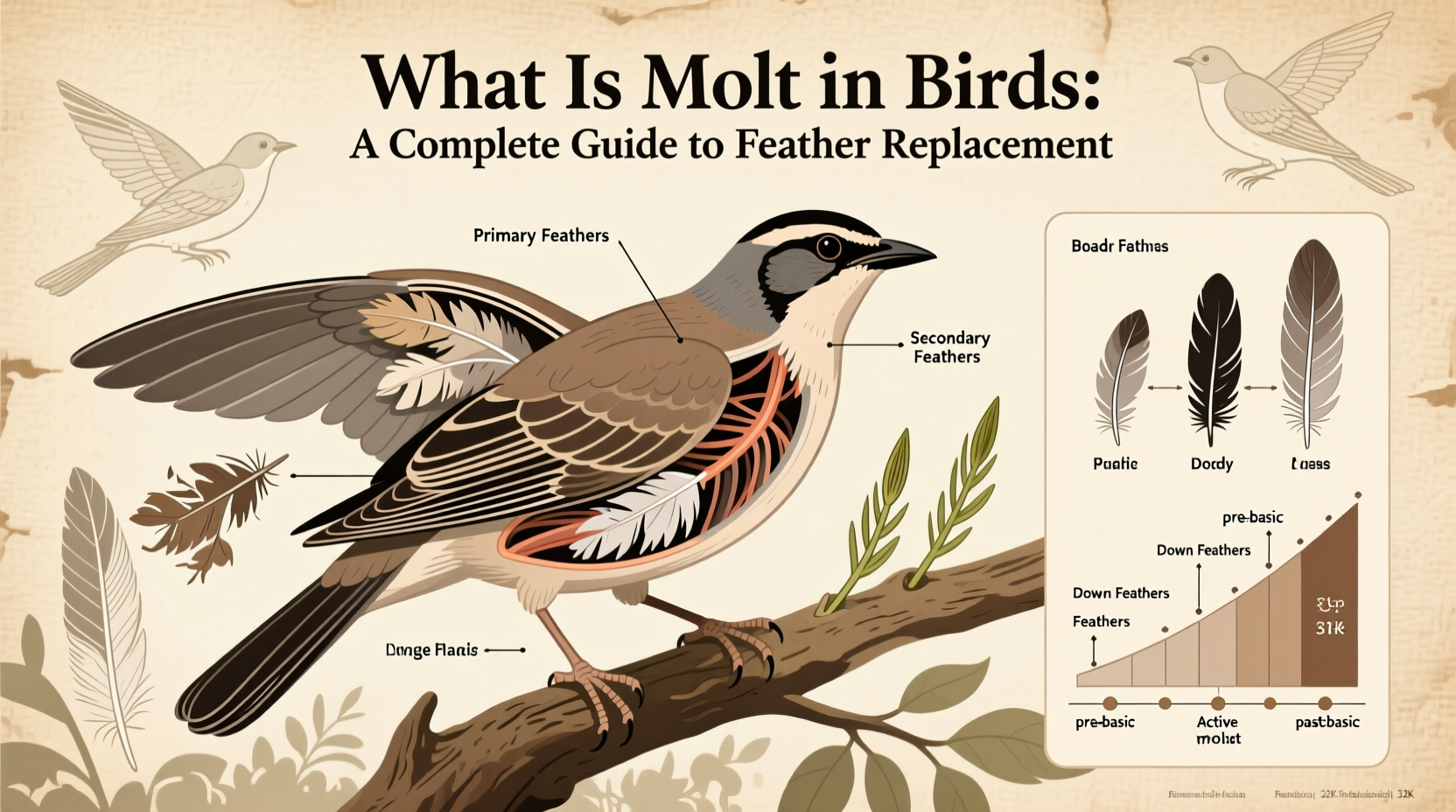

Feathers are made of keratinâthe same protein found in human hair and nailsâand while strong, they wear down over time due to sun exposure, physical abrasion, and parasites. Unlike mammals that continuously grow hair, birds replace their feathers in coordinated cycles known as molts. The timing, duration, and pattern of molting vary significantly among species, but all molts serve the same fundamental purpose: renewal.

Birds typically undergo a complete molt at least once per year, often after breeding season when food is still abundant and energetic demands are lower. Some species, like many warblers and sparrows, experience a partial prealternate molt in late winter or early spring, replacing body feathers but not flight feathers, resulting in brighter breeding plumage. Others, such as ducks and geese, may undergo a simultaneous wing molt, rendering them temporarily flightless.

Molting is hormonally regulated, primarily by thyroid and prolactin hormones, which respond to environmental cues such as day length (photoperiod), temperature, and food availability. Because growing new feathers requires substantial protein and energy, birds often reduce other high-cost activitiesâlike migration or breedingâduring active molt periods.

Types of Molts in Birds

Birds exhibit several distinct types of molting patterns based on timing, extent, and sequence:

- Prebasic Molt: This is the most common and comprehensive feather replacement, occurring after the breeding season. It usually results in the birdâs basic (non-breeding) plumage.

- Prealternate Molt: A less extensive molt before the breeding season, seen in some songbirds and shorebirds. It often enhances coloration for mating displays without replacing flight feathers.

- Partial vs. Complete Molt: In a partial molt, only certain feather tracts (such as head or body feathers) are replaced. A complete molt involves nearly all feathers.

- Simultaneous vs. Sequential Molt: Waterfowl like mallards lose all their flight feathers at once, becoming flightless for 3â4 weeks. Most passerines molt flight feathers gradually, one or two at a time, preserving flight ability.

Understanding these variations helps explain why a single species might look dramatically different across seasonsâa key consideration for accurate bird identification.

Why Do Birds Molt? Evolutionary and Ecological Reasons

Molting serves multiple adaptive functions beyond simple wear and tear repair. These include:

- Flight Efficiency: Damaged or frayed wing feathers impair aerodynamics. Replacing them ensures efficient flight for migration, foraging, and predator evasion.

- Thermoregulation: Feathers provide critical insulation. A fresh coat of contour and down feathers improves heat retention during colder months.

- Camouflage and Signaling: Seasonal plumage changes help birds blend into changing environments or signal fitness during mating season. For example, male American goldfinches turn bright yellow in spring via prealternate molt to attract mates.

- Parasite Reduction: Shedding old feathers can remove ectoparasites like lice and mites that cling to feather shafts.

From an evolutionary standpoint, molting represents a trade-off between survival and reproduction. Birds must time their molt carefully to avoid overlapping with energetically costly events like nesting or long-distance migration.

When Does Molt Occur? Timing Across Species and Regions

The timing of molt varies widely depending on species, geographic location, climate, and life history. However, general patterns exist:

- Temperate Zone Birds: Most undergo prebasic molt in late summer to early fall (JulyâSeptember). Songbirds like robins and blue jays begin molting shortly after fledging their last brood.

- Tropical Birds: With less seasonal variation, molt schedules may be more flexible or spread throughout the year. Some tropical species molt slowly over many months. \li>Arid and Desert Species: May delay molt until after rains bring increased food resources.

- Migratory Birds: Often complete their post-breeding molt before departure. Some shorebirds even initiate molt while en route or upon reaching wintering grounds.

For birdwatchers, recognizing molt timing helps interpret plumage anomalies. A bird appearing scruffy or with mismatched feathers in August is likely mid-moltânot injured.

How Long Does Molt Last?

The duration of molt depends on the species and type of molt. Small passerines may take 6â8 weeks to complete a full prebasic molt, while larger birds like eagles or swans can take several months. Flightless waterfowl go through a rapid but intense 3â5 week simultaneous wing molt.

Feather growth rate is remarkably consistent within species. Primary feathers grow at about 3â4 mm per day in small birds, meaning a 70 mm primary takes roughly 18â24 days to fully emerge from its sheath. Because growing too many feathers at once would be metabolically overwhelming, most birds molt symmetrically and sequentiallyâone feather at a timeâto balance energy use and maintain functionality.

Energy Demands and Behavioral Changes During Molt

Molting is one of the most physiologically demanding processes in a birdâs annual cycleâsecond only to reproduction. Growing new feathers requires large amounts of dietary protein, sulfur-containing amino acids (like cysteine), and micronutrients such as zinc and iron.

To meet these needs, birds often alter their behavior:

- Increase feeding time, especially on insect-rich diets high in protein.

- Reduce territorial defense and singing activity.

- Avoid unnecessary flights to conserve energy.

- Seek dense cover for protection, as reduced plumage can compromise insulation and camouflage.

Birdwatchers may notice fewer vocalizations or sightings during peak molt months, not because populations have declined, but because birds are less conspicuous.

Molt and Plumage Variation: Challenges for Identification

One of the biggest challenges in field ornithology is identifying birds during molt. Mixed plumagesâwhere old and new feathers coexistâcan create misleading appearances. For instance:

- A molting gull may show patchy gray and white feathers, making age classification difficult.

- A male cardinal replacing duller post-breeding feathers with bright red ones may appear unevenly colored.

- Juvenile birds undergoing their first prebasic molt may resemble adults incompletely.

Field guides increasingly include molt-specific illustrations, and experienced birders use clues like feather wear, shape, and symmetry to determine molt stage. Digital photography has greatly aided this effort, allowing detailed examination of individual feathers.

| Bird Group | Typical Molt Period | Molt Type | Flightless? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passerines (e.g., sparrows, finches) | JulyâSeptember | Complete, sequential | No |

| Ducks (e.g., mallards) | AugustâSeptember | Simultaneous wing + body | Yes (3â4 weeks) |

| Raptors (e.g., hawks) | SpringâFall (gradual) | Slow, staggered | No |

| Shorebirds (e.g., sandpipers) | JulyâOctober | Complete prebasic; partial prealternate | No |

| Tropical Parrots | Year-round (slow) | Gradual, incomplete | No |

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings of Molt

Beyond biology, the concept of molt resonates deeply in human culture and symbolism. Across mythologies and spiritual traditions, feather shedding represents transformation, renewal, and personal growth. Native American cultures often view molting birds as symbols of rebirth and adaptability. In modern psychology, the phrase "going through a molt" is sometimes used metaphorically to describe periods of personal change or healing.

In literature and art, molting appears as a motif of impermanence and resilience. Just as a bird must endure the awkward phase of patchy feathers to regain strength, humans are reminded that vulnerability can precede renewal.

Supporting Birds During Molt: Tips for Birdwatchers and Caretakers

If you maintain bird feeders or care for captive birds, there are practical steps you can take to support healthy molting:

- Provide High-Protein Foods: Offer black oil sunflower seeds, peanuts, mealworms, or suet during late summer and fall.

- Ensure Clean Water: Bathing helps birds remove old feather sheaths and parasites.

- Minimize Stressors: Reduce disturbances near nesting or roosting areas during peak molt.

- For Aviculturists: Supplement diets with amino acids and vitamins, especially lysine, methionine, and B-complex vitamins.

- Avoid Handling Wild Birds: Molting feathers are sensitive; handling can cause pain or damage developing pin feathers.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Molt

Several myths persist about feather replacement in birds:

- Myth: Bald cardinals are caused by disease.

Reality: While possible, seasonal baldness in northern cardinals is often a normal, albeit extreme, molt variantâespecially in males during July and August. - Myth: All birds molt once a year.

Reality: Many undergo two molts annually (prebasic and prealternate), and some tropical species molt irregularly. - Myth: Molt always follows breeding.

Reality: Some seabirds molt before breeding, and juveniles often have unique molt schedules separate from adults. - Myth: Flightlessness means injury.

Reality: Ducks and geese naturally become flightless during simultaneous wing moltâit's a normal part of their annual cycle.

How to Observe and Document Molt

Birdwatchers can contribute valuable data by noting molt patterns in the field. Hereâs how:

- Look for signs: ragged wing edges, visible skin patches, or asymmetrical plumage.

- Use binoculars or telephoto lenses to examine primary feather growth stages.

- Photograph individuals over time to track progression.

- Record observations in apps like eBird, noting any molt-related comments.

- Consult specialized resources like The Manual of Ornithology or online databases such as Birds of the World for species-specific molt sequences.

Citizen science projects increasingly rely on accurate molt documentation to study climate change impacts, population health, and phenological shifts.

Frequently Asked Questions About Bird Molt

What does molt mean in birds?

Molt refers to the natural process by which birds shed old or damaged feathers and grow new ones to maintain flight, insulation, and appearance.

Do all birds molt?

Yes, all bird species undergo some form of molt, though the frequency, timing, and extent vary widely depending on species, age, and environment.

Why do some birds look scruffy in summer?

Scruffy appearance during summer months is typically due to active molting, especially after breeding season, when birds replace worn feathers.

Can molting affect bird behavior?

Yesâbirds often reduce singing, become less active, and seek shelter during molt due to increased energy demands and temporary reductions in flight efficiency or camouflage.

How can I help birds during molt?

You can support molting birds by providing high-protein foods, clean water for bathing, and minimizing habitat disturbances during peak molt seasons (late summer to early fall).

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4