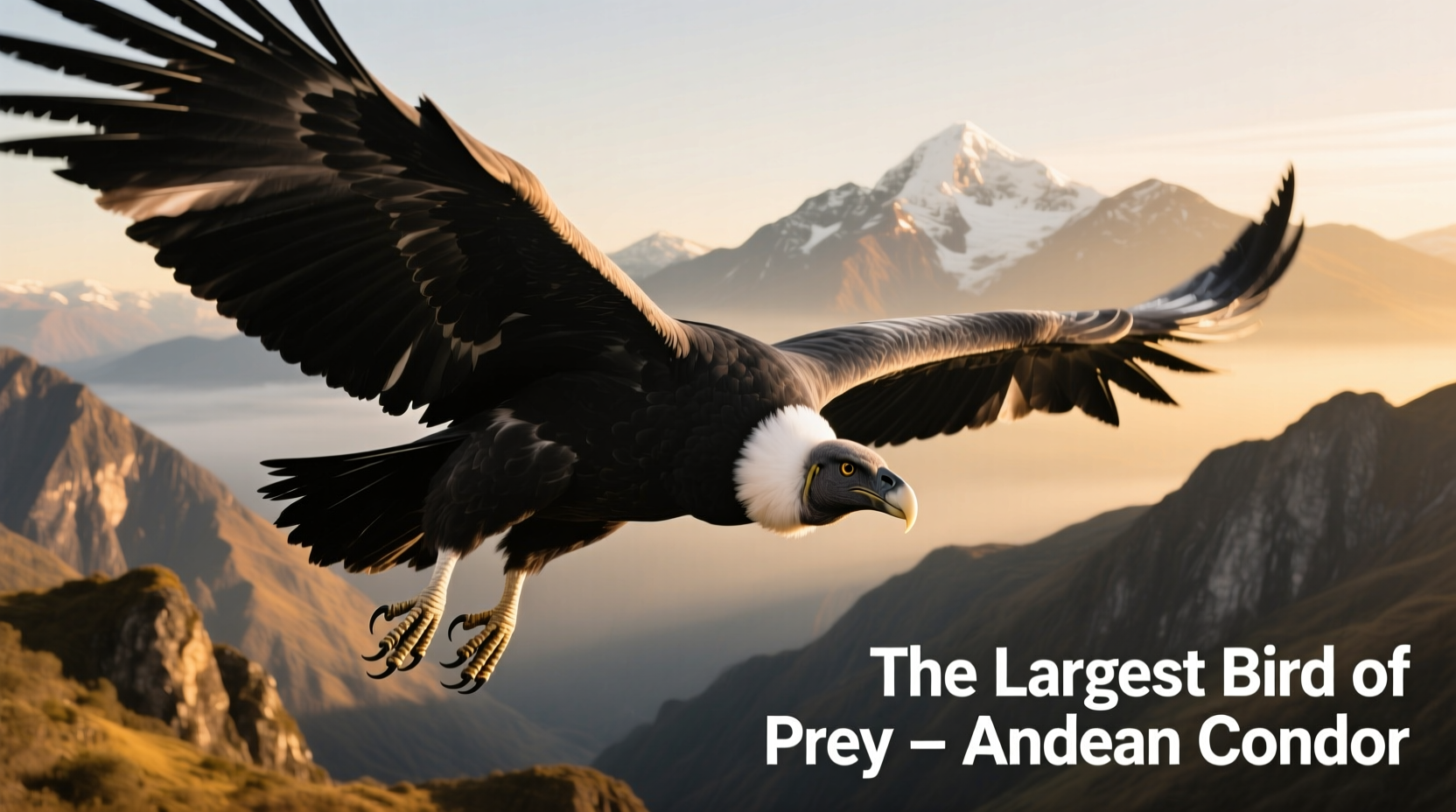

The biggest bird of prey in the world is the Andean condor (Vultur gryphus), a majestic raptor renowned for its enormous wingspan and powerful presence in the skies of South America. With a maximum wingspan exceeding 10.5 feet (3.2 meters) and weights reaching up to 33 pounds (15 kilograms), the Andean condor stands as the largest extant bird of prey based on both bulk and soaring capability. This colossal scavenger, often mistaken for a predator due to its size and hooked beak, plays a crucial ecological role as nature’s cleanup crew across the Andes Mountains. Understanding what is the biggest bird of prey involves not only measuring physical dimensions but also appreciating flight dynamics, feeding behavior, and conservation status—key aspects that define the true scale of dominance in the avian world.

Defining 'Biggest' in Birds of Prey

When exploring what is the biggest bird of prey, it's essential to clarify how “biggest” is measured. Size can be assessed through several metrics: wingspan, body length, weight, or overall mass. While some raptors may excel in one category, the Andean condor leads in two critical areas—wingspan and weight—making it the most comprehensive answer to this question. For example, the Steller’s sea eagle has a heavier bill and denser build, but it weighs significantly less than the male Andean condor. Similarly, the California condor, though closely related, averages smaller in both wingspan and mass.

In ornithology, birds of prey—also known as raptors—include eagles, hawks, falcons, vultures, ospreys, and owls. However, not all large raptors are active hunters. The Andean condor, despite being classified among birds of prey due to taxonomic grouping and physical traits like sharp talons and hooked beaks, is primarily a scavenger. This distinction sometimes causes confusion when determining which species qualifies as the ‘biggest,’ especially since many assume predation defines raptor status.

Physical Characteristics of the Andean Condor

The Andean condor exhibits extraordinary adaptations suited to life at high altitudes and vast open terrains. Males typically outweigh females, with average weights between 24–33 lbs (11–15 kg), while females range from 18–24 lbs (8–11 kg). Their wingspan averages 9.8 feet (3 meters), with verified records surpassing 10.5 feet—longer than a compact car is wide.

Feather coloration is predominantly black with striking white secondary feathers forming a collar around the thighs and upper wings. Adult males possess a large caruncle—a fleshy crest—on the crown, used in social displays and mate selection. Their nearly featherless head and neck help maintain hygiene while feeding on carrion, reducing bacterial buildup from decaying flesh.

Unlike predatory raptors such as golden eagles, the Andean condor’s talons are relatively weak, unsuitable for killing prey. Instead, they rely on their massive beak to tear through tough hides of dead animals. Their skeletal structure includes hollow bones typical of birds, yet reinforced for stability during thermal soaring over mountainous regions.

Habitat and Geographic Range

The Andean condor inhabits the western edge of South America, primarily along the Andes mountain range stretching from Venezuela and Colombia in the north to Chile and Argentina in the south. They favor elevations between 3,000 and 16,000 feet (900–4,800 meters), where strong updrafts and thermals allow effortless gliding. Cliffs and rocky outcrops serve as nesting sites, often reused for generations.

Populations are fragmented today due to habitat loss and human activity. Conservation efforts have reintroduced them into parts of Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia where local extinction had occurred. In Argentina’s Patagonia region and the Atacama Desert of northern Chile, healthy populations still soar above remote valleys and coastal cliffs.

| Bird Species | Average Wingspan | Average Weight | Primary Diet | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andean Condor | 9.8–10.5 ft (3.0–3.2 m) | 24–33 lb (11–15 kg) | Carrion | Andes Mountains, South America |

| California Condor | 9.5 ft (2.9 m) | 17–25 lb (7.7–11.3 kg) | Carrion | Western USA, Baja California |

| Wedge-tailed Eagle | 6.9–8.2 ft (2.1–2.5 m) | 7.7–10.8 lb (3.5–4.9 kg) | Small mammals, reptiles | Australia, southern New Guinea |

| Steller’s Sea Eagle | 6.6–8.2 ft (2.0–2.5 m) | 12–20 lb (5.5–9.0 kg) | Fish, waterfowl | North Pacific Rim |

Flight Mechanics and Soaring Efficiency

One reason the Andean condor can sustain flight for hours without flapping its wings lies in its mastery of dynamic soaring and thermal lift. By riding rising warm air currents, these birds gain altitude effortlessly, sometimes reaching heights over 16,000 feet. Once aloft, they glide for miles, scanning the terrain below for carcasses using exceptional eyesight.

Studies using GPS tracking reveal that individual condors may travel more than 100 miles (160 km) in a single day while expending minimal energy. This efficiency is vital given their scavenging lifestyle—food sources are unpredictable and widely dispersed. Their wing loading (weight per unit wing area) is optimized for slow, stable flight rather than rapid maneuvers, distinguishing them from agile hunters like peregrine falcons.

Diet and Ecological Role

As obligate scavengers, Andean condors feed almost exclusively on carrion—from deer and livestock to marine mammals washed ashore along the Pacific coast. They play a critical role in preventing disease spread by rapidly consuming decomposing remains. Despite their size, they rarely kill live prey, though juveniles may occasionally attack weak or newborn animals.

They often feed in groups, with dominant males asserting priority access. Smaller scavengers like foxes and turkey vultures benefit indirectly, feeding on scraps left behind. This hierarchical feeding system highlights the condor’s position at the top of the scavenger chain.

Cultural Significance Across South America

Beyond biology, the Andean condor holds profound symbolic meaning in indigenous Andean cultures. Revered as a messenger between the earthly realm and the spirit world, it features prominently in myths, ceremonies, and national emblems. In countries like Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, and Colombia, the condor represents power, freedom, and resilience.

The phrase 'Yayakuna punchaw' ('day of the condors') appears in Quechua traditions, referring to times of spiritual renewal. In modern times, live condors are sometimes displayed during festivals, though conservationists caution against stress-inducing practices. The bird also appears on national coats of arms and currency, underscoring its cultural importance.

Conservation Status and Threats

The Andean condor is currently listed as Near Threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), with an estimated wild population of fewer than 10,000 individuals. Primary threats include lead poisoning from ingesting bullet fragments in carcasses, habitat fragmentation, and persecution by ranchers who mistakenly believe they attack livestock.

Conservation programs across South America focus on captive breeding, public education, and anti-poisoning campaigns. In Argentina and Chile, protected corridors allow safe movement between feeding and nesting zones. Reintroduction projects have successfully restored populations in areas like the Colombian Andes and the Ecuadorian páramo ecosystems.

How to See the Andean Condor in the Wild

For birdwatchers and ecotourists seeking to observe the biggest bird of prey in its natural environment, several locations offer reliable sightings:

- Colca Canyon, Peru: One of the best-known spots, where early morning thermals draw condors into view. Tours depart daily from nearby villages.

- Toro Toro National Park, Bolivia: Home to a reintroduced population; guided hikes increase sighting chances.

- El Chaltén, Argentina: Located in Los Glaciares National Park, this area offers dramatic aerial views of condors near Mount Fitz Roy.

- Altos de Cantillana, Chile: A conservation reserve near Santiago with monitoring stations and observation decks.

Best viewing times are mid-morning to early afternoon when thermals develop. Bring binoculars or a spotting scope, and consider hiring a local guide familiar with flight patterns. Always maintain a respectful distance to avoid disturbing nesting or feeding behaviors.

Common Misconceptions About the Andean Condor

Several myths persist about this giant raptor. One common misconception is that it attacks humans or livestock regularly. There is no documented case of an Andean condor preying on a healthy adult human, and attacks on live cattle are extremely rare and usually involve already dying animals.

Another myth suggests that all large flying birds are predators. While the condor looks fearsome, its anatomy clearly reflects scavenging adaptation—not hunting. Lastly, some confuse it with the California condor, which, although similar in appearance and ecology, is genetically distinct and geographically separate.

Comparison with Other Large Raptors

While the Andean condor holds the title for largest bird of prey overall, other raptors challenge it in specific categories:

- Philippine Eagle: Though lighter (up to 14 lbs / 6.5 kg), it has a longer body and is considered the largest eagle by length.

- Harpy Eagle: Extremely powerful legs and talons, capable of taking sloths and monkeys, but much shorter wingspan (~6.5 ft).

- Martial Eagle: Africa’s largest eagle, weighing up to 14 lbs, known for aggressive predation.

None, however, match the Andean condor’s combination of sheer mass and aerodynamic scale.

FAQs About the Biggest Bird of Prey

- Is the Andean condor the largest flying bird in the world?

- No, while it is the largest bird of prey, larger birds like the wandering albatross (longer wingspan) and certain bustards (heavier) exist, but they are not classified as raptors.

- Can the Andean condor fly long distances without flapping?

- Yes, it can travel hundreds of kilometers using thermal currents and wind patterns, flapping its wings only occasionally.

- Why do Andean condors have bald heads?

- Baldness helps prevent bacteria and parasites from clinging to feathers when feeding inside carcasses, promoting hygiene.

- Are there any birds bigger than the Andean condor in history?

- Yes, extinct species like Pelagornis sandersi, a prehistoric seabird, had an estimated wingspan of up to 21 feet, far exceeding any living bird.

- How long do Andean condors live?

- In the wild, they live around 50 years; in captivity, some individuals have exceeded 70 years, making them among the longest-lived birds.

In conclusion, the Andean condor reigns supreme as the biggest bird of prey alive today. Its unmatched wingspan, commanding weight, and vital ecological function make it a symbol of wilderness and endurance. Whether viewed through a biological lens or appreciated for its cultural legacy, this magnificent raptor continues to inspire awe and demand protection for future generations to witness its silent glide above the Andes.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4