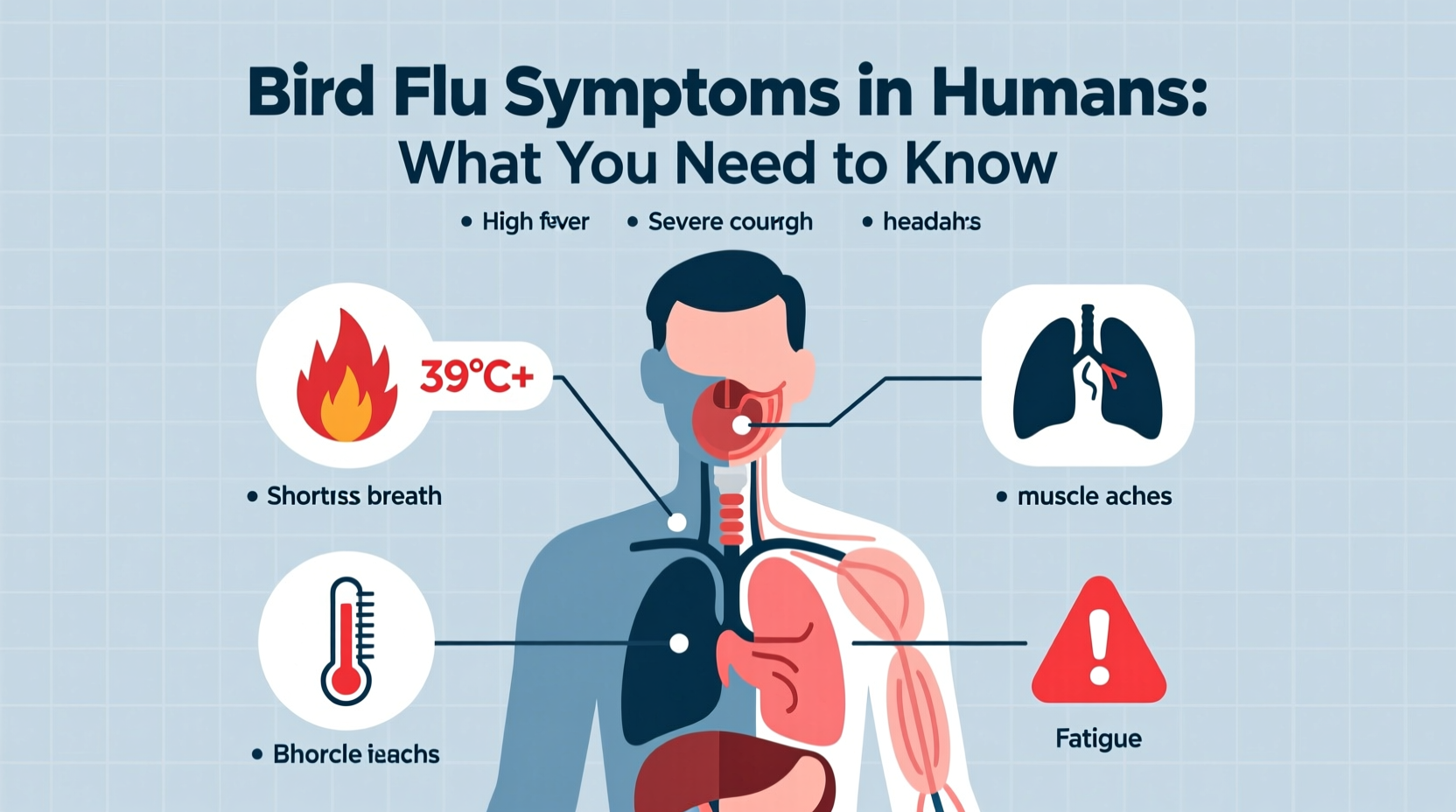

Bird flu symptoms in humans typically include fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, and shortness of breath—symptoms that closely resemble those of seasonal influenza but may rapidly progress to severe respiratory illness. A key indicator tied to recent outbreaks is the presence of conjunctivitis or eye infections alongside typical flu-like signs, especially among individuals with recent exposure to infected poultry. This variation—often referred to as 'avian influenza symptoms in humans 2024'—is critical for early detection and containment.

Understanding Bird Flu: A Dual Perspective of Biology and Public Health

Bird flu, or avian influenza, is caused by Type A influenza viruses that primarily affect birds. While these viruses circulate naturally among wild aquatic birds—such as ducks, gulls, and shorebirds—they can spread to domestic poultry like chickens, turkeys, and quails, leading to high mortality rates in flocks. Occasionally, the virus jumps species barriers and infects humans, usually through direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environments. The most concerning strains from a public health standpoint are H5N1, H7N9, and more recently, H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, which has been responsible for widespread outbreaks in both wild and domestic birds globally since 2021.

Common Symptoms of Avian Influenza in Humans

When bird flu does infect humans, the clinical presentation can vary significantly depending on the viral strain, route of exposure, and individual immune response. However, common bird flu symptoms in people include:

- Fever (often above 38°C / 100.4°F)

- Cough (usually dry)

- Sore throat

- Muscle pain (myalgia)

- Headache

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

- Conjunctivitis (pink eye), particularly noted in H7 subtype infections

- Diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain (more common than in seasonal flu)

In severe cases, the infection can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), pneumonia, multi-organ failure, and death. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports case fatality rates exceeding 50% for certain strains like H5N1, though human-to-human transmission remains rare and inefficient.

Distinguishing Bird Flu from Seasonal Flu

One of the biggest challenges in diagnosing avian influenza is its similarity to common seasonal influenza. Both share overlapping symptoms such as fever, fatigue, and respiratory discomfort. However, there are distinguishing features:

| Symptom | Bird Flu (e.g., H5N1) | Seasonal Human Flu |

|---|---|---|

| Onset Speed | Rapid progression within days | Gradual over 1–2 days |

| Gastrointestinal Symptoms | Common (diarrhea, nausea) | Rare |

| Conjunctivitis | Frequent in some subtypes | Very rare |

| Severity | High risk of hospitalization | Usually mild to moderate |

| Exposure History | Recent contact with sick/dead birds | Contact with infected persons |

Therefore, medical professionals rely heavily on epidemiological history—especially travel to affected regions or involvement in poultry farming—to suspect bird flu early.

Transmission Pathways and Risk Factors

Human infection generally occurs through:

- Direct contact with infected live or dead birds

- Handling raw or undercooked poultry products

- Exposure to contaminated surfaces (e.g., cages, feathers, feces)

- Inhalation of aerosolized particles in enclosed spaces like live bird markets

People at highest risk include poultry farmers, veterinarians, cullers during outbreak responses, and those living in rural areas where backyard flocks mix with migratory birds. Despite fears, consumption of properly cooked poultry and eggs does not transmit the virus—the heat destroys it. However, cross-contamination during food preparation remains a potential hazard.

Global Outbreak Trends and Surveillance

The current wave of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), particularly H5N1, has spread across continents since 2021, affecting over 80 countries. In 2024, outbreaks were reported in commercial farms in the United States, the United Kingdom, India, Japan, and several African nations. Wild bird migration plays a major role in long-distance dissemination. For instance, the spring and fall migrations allow viruses to move along flyways, infecting new populations.

Organizations like the WHO, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) maintain global surveillance systems. These networks monitor unusual bird deaths, test samples, and issue alerts to national authorities. Real-time data sharing helps governments implement control measures such as movement restrictions, culling, and vaccination programs.

Prevention and Protective Measures

Preventing bird flu involves both personal precautions and systemic controls. Key strategies include:

- Avoid contact with sick or dead birds: Do not touch or handle any bird found dead unless instructed by local wildlife or agricultural agencies.

- Practice biosecurity on farms: Farmers should isolate domestic birds from wild ones, disinfect equipment, and limit visitor access.

- Use protective gear: Workers handling birds should wear gloves, masks (N95 respirators), goggles, and disposable clothing.

- Cook poultry thoroughly: Ensure meat reaches an internal temperature of at least 74°C (165°F) and eggs are fully cooked.

- Wash hands frequently: Especially after visiting markets or farms.

- Report unusual bird deaths: Contact local animal health departments immediately.

Vaccination of poultry is used in some countries, although it doesn't always prevent infection—it reduces shedding and mortality. No widely approved human vaccine exists yet, though experimental candidates are being tested.

Diagnosis and Medical Response

If bird flu is suspected based on symptoms and exposure history, healthcare providers perform diagnostic tests using respiratory specimens (nasopharyngeal swabs). Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays can identify specific avian influenza strains. Rapid antigen tests are less reliable and not recommended for definitive diagnosis.

Treatment typically involves antiviral medications such as oseltamivir (Tamiflu), zanamivir (Relenza), or peramivir, ideally administered within 48 hours of symptom onset. Supportive care in hospitals—including oxygen therapy and mechanical ventilation—is often required for severe cases. Isolation protocols are followed to prevent possible secondary transmission.

Cultural and Symbolic Dimensions of Birds and Disease

Birds have long held symbolic significance across cultures—representing freedom, spirituality, messengers between realms, or omens. In many traditions, sudden mass bird deaths are interpreted as harbingers of disaster or imbalance in nature. While modern science explains such events through virology and ecology, cultural narratives still influence public perception during outbreaks.

For example, in parts of Southeast Asia, where backyard poultry keeping is common and deeply embedded in daily life, fear of bird flu has disrupted traditional practices involving roosters in cockfighting or temple offerings. Similarly, indigenous communities dependent on migratory birds for subsistence face both nutritional and spiritual impacts when hunting bans are imposed during outbreaks.

Understanding these dimensions is crucial for effective communication. Public health campaigns must respect cultural values while promoting safety—balancing scientific facts with community trust.

Myths and Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about avian influenza:

- Myth: Eating chicken causes bird flu.

Fact: Properly cooked poultry is safe. The virus is destroyed at cooking temperatures. - Myth: Bird flu spreads easily between people.

Fact: Sustained human-to-human transmission has not occurred. Most cases result from animal contact. - Myth: All bird deaths are due to bird flu.

Fact: Many factors—including poisoning, habitat loss, and other diseases—can cause bird mortality. - Myth: There’s a vaccine for humans available now.

Fact: While candidate vaccines exist, none are commercially licensed for general use.

How to Stay Updated on Bird Flu Activity

Because outbreaks evolve rapidly, staying informed is essential. Reliable sources include:

- World Health Organization (who.int)

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc.gov/flu)

- Food and Agriculture Organization (fao.org/avian-flu)

- National veterinary or public health agencies

Local news outlets and government bulletins also provide timely updates on regional risks, travel advisories, and farm closures. Travelers to rural areas in affected countries should check entry requirements and avoid live bird markets.

FAQs: Frequently Asked Questions About Bird Flu Symptoms

What are the first signs of bird flu in humans?

The first signs typically include sudden fever, cough, and sore throat—similar to regular flu—but often accompanied by diarrhea or conjunctivitis, especially if there's known exposure to infected birds.

Can you get bird flu from eating eggs?

No, not if they are properly cooked. The virus is killed at standard cooking temperatures. Avoid consuming raw or soft-boiled eggs from areas experiencing outbreaks.

Is bird flu contagious between humans?

Currently, bird flu does not spread efficiently between people. Most infections occur through direct bird contact. Limited person-to-person transmission has occurred in rare household settings but hasn’t led to sustained outbreaks.

How long after exposure do symptoms appear?

Symptoms usually develop within 2 to 8 days after exposure, though incubation can extend up to 10 days in some cases.

Are pets like cats at risk of catching bird flu?

Yes, especially if they hunt or consume infected birds. Feline infections have been documented with H5N1, sometimes leading to severe illness or death. Keep cats indoors during local outbreaks.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4