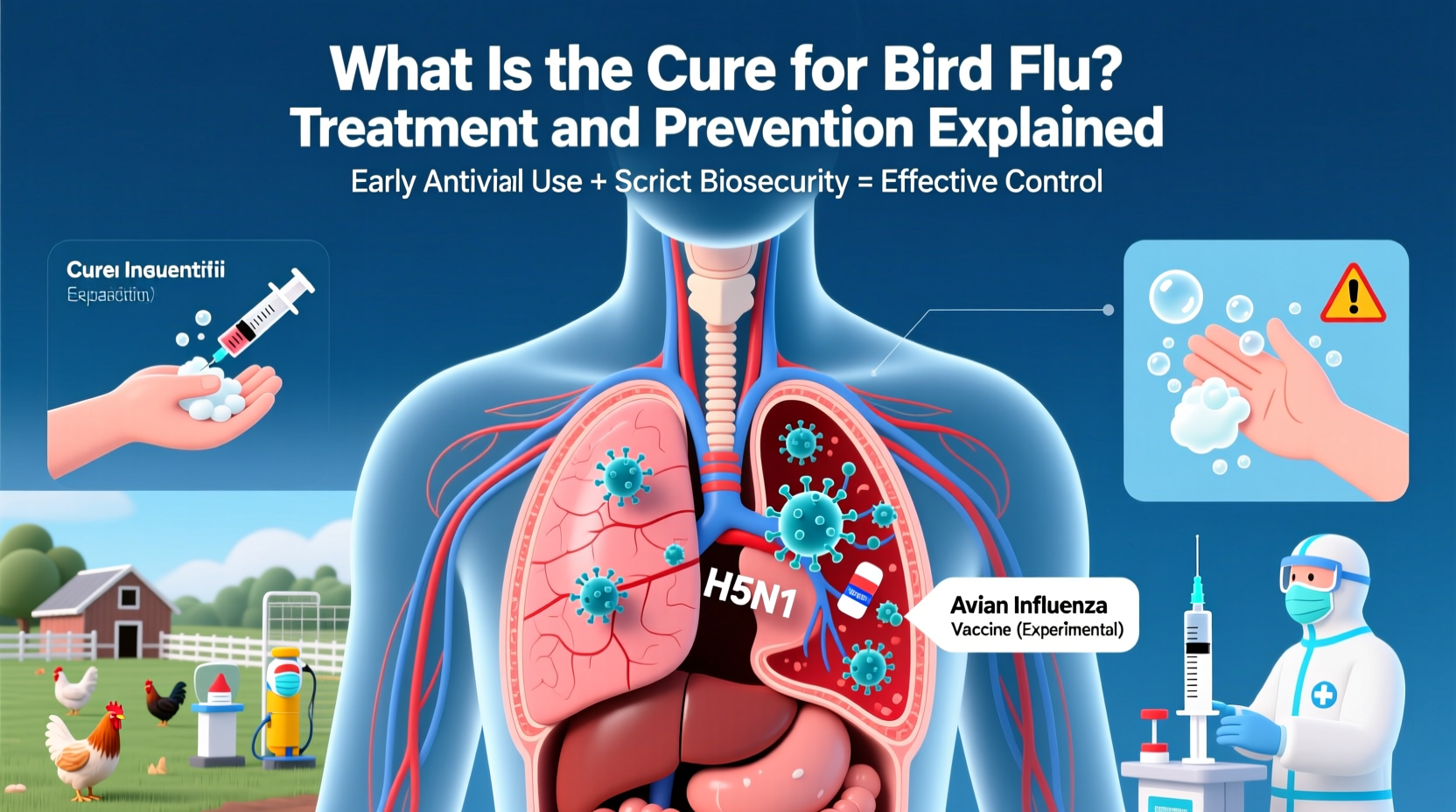

There is currently no universal cure for bird flu, also known as avian influenza, but effective treatment and control strategies focus on antiviral medications, outbreak containment, and preventive measures in both poultry and humans. The most promising treatments involve neuraminidase inhibitors such as oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir, which can reduce the severity and duration of illness if administered early. Understanding what is the cure for bird flu requires a multidimensional approach that includes veterinary public health, biosecurity practices, and global surveillance systems to monitor emerging strains like H5N1 and H7N9. While research into universal vaccines continues, current efforts emphasize rapid detection, culling infected flocks, and minimizing human exposure.

Understanding Bird Flu: A Biological Overview

Bird flu is caused by infection with avian influenza Type A viruses, which naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds such as ducks, gulls, and shorebirds. These viruses belong to the Orthomyxoviridae family and are classified based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). Over a dozen H subtypes exist, but H5 and H7 are of greatest concern due to their potential to mutate from low pathogenic forms (LPAI) into highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), capable of causing mass mortality in domestic poultry.

The transmission of avian influenza primarily occurs through direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environments, including feces, saliva, and respiratory secretions. While most strains do not easily infect humans, certain subtypes—particularly H5N1 and H7N9—have crossed the species barrier, leading to severe respiratory illness and high fatality rates in people exposed to live bird markets or infected poultry farms.

Current Medical Treatments for Human Cases

When considering what is the cure for bird flu in humans, it's important to clarify that there is no standalone 'cure' per se, but rather medical interventions aimed at mitigating symptoms and preventing complications. Antiviral drugs approved for seasonal influenza have been repurposed for avian flu under emergency use protocols:

- Oseltamivir (Tamiflu): An oral neuraminidase inhibitor effective when taken within 48 hours of symptom onset. It reduces viral replication and lowers the risk of pneumonia and death.

- Zanamivir (Relenza): Inhaled antiviral suitable for patients without underlying respiratory conditions. Not recommended for those with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Peramivir (Rapivab): Intravenous formulation used in hospitalized patients unable to take oral medication.

- Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza): A newer cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor that blocks viral mRNA synthesis. Its efficacy against avian strains is still under investigation.

Supportive care—including oxygen therapy, mechanical ventilation, and management of secondary bacterial infections—remains critical in severe cases. Clinical trials continue to evaluate combination therapies and monoclonal antibodies targeting conserved regions of the virus.

Vaccination Strategies in Poultry and Humans

Vaccination plays a key role in controlling bird flu outbreaks in agricultural settings. Several inactivated whole-virus vaccines are used globally, particularly in countries with large poultry industries such as China, Vietnam, and Egypt. However, vaccination does not eliminate the virus; instead, it reduces shedding and clinical signs, making surveillance more challenging. Therefore, vaccination must be paired with strict biosecurity and monitoring programs.

In humans, no commercially available vaccine exists specifically for widespread protection against all avian influenza strains. However, pre-pandemic vaccines have been developed for H5N1 and H7N9 and are stockpiled by some governments as part of pandemic preparedness plans. These vaccines require adjuvants to enhance immune response and often necessitate two doses. Ongoing research focuses on developing a universal influenza vaccine that targets conserved viral epitopes across multiple subtypes.

Global Surveillance and Outbreak Response

Early detection is essential to prevent localized outbreaks from escalating into regional or global threats. The World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the World Health Organization (WHO) collaborate on real-time reporting through platforms like EMPRES-i and Flunet. These systems track avian influenza in wild and domestic birds, enabling rapid deployment of containment measures.

When an outbreak occurs, standard responses include:

- Culling of infected and exposed flocks

- Establishment of quarantine zones (typically 3–10 km radius)

- Banning of live bird movements

- Enhanced disinfection of farms, transport vehicles, and markets

- Surveillance of contacts, including farm workers and veterinarians

These actions aim to break the transmission chain and prevent spillover into human populations.

Prevention and Biosecurity Best Practices

For backyard poultry owners and commercial farmers alike, implementing robust biosecurity measures is the most effective way to prevent bird flu introduction. Key recommendations include:

- Limiting access to poultry areas by visitors and non-essential personnel

- Using dedicated clothing and footwear for handling birds

- Disinfecting equipment and vehicles regularly

- Avoiding mixing different bird species or sourcing birds from unknown origins

- Providing feed and water in enclosed areas to deter wild birds

- Monitoring flocks daily for signs of illness (e.g., decreased egg production, nasal discharge, swelling around eyes)

Public health authorities advise against visiting live bird markets in regions experiencing outbreaks and recommend thorough handwashing after any bird contact.

Cultural and Symbolic Perspectives on Birds and Disease

Birds have long held symbolic significance across cultures—as messengers, omens, and spiritual intermediaries. In many traditions, sudden bird deaths or unusual behavior are interpreted as harbingers of change or danger. For instance, in Celtic mythology, ravens were associated with war and prophecy; their disappearance might signal impending doom. Similarly, in parts of Southeast Asia, where duck farming is deeply embedded in rural life, the culling of flocks during bird flu outbreaks carries emotional and cultural weight beyond economic loss.

These symbolic associations can influence public perception and response during epidemics. Misinformation may spread if communities interpret bird die-offs through mythological rather than scientific lenses. Effective communication strategies must therefore integrate cultural sensitivity with accurate health messaging to promote compliance with control measures.

Regional Differences in Bird Flu Management

Approaches to managing avian influenza vary significantly by region due to differences in agriculture, regulation, and healthcare infrastructure. In high-income countries like the United States and members of the European Union, advanced surveillance networks and rapid-response teams enable swift containment. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) operates the National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP), which sets standards for flock certification and disease prevention.

In contrast, resource-limited settings face challenges such as informal poultry trade, limited diagnostic capacity, and delayed reporting. Migratory bird flyways further complicate control, as viruses can be introduced seasonally from distant regions. Countries along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, for example, experience recurring waves of H5N1 linked to wild bird migration patterns.

| Region | Common Strains | Primary Control Methods | Vaccination Policy |

|---|---|---|---|

| North America | H5N1, H7N3 | Culling, movement restrictions | No routine vaccination |

| Europe | H5N1, H5N8 | Quarantine, surveillance | Limited, targeted use |

| East Asia | H5N1, H7N9 | Vaccination, market closures | Widespread vaccination |

| Africa | H5N1 | Community education, culling | Ad hoc, donor-supported |

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about avian influenza, hindering effective response. One common belief is that eating properly cooked poultry or eggs can transmit the virus. This is false—avian influenza is destroyed at temperatures above 70°C (158°F), making well-cooked food safe. Another misconception is that pet birds are major carriers; while possible, the risk is minimal if they are kept indoors and away from wild birds.

Some people assume that seasonal flu vaccines offer protection against bird flu. They do not, as these vaccines target human-adapted strains. Lastly, there is confusion over whether bird flu spreads easily between humans. Sustained human-to-human transmission has not been documented, though rare cases of limited transmission among close contacts have occurred.

Future Directions in Research and Policy

Scientists are exploring next-generation solutions to address the limitations of current bird flu controls. Promising avenues include gene-editing technologies like CRISPR to develop influenza-resistant poultry, recombinant vaccines that provide broader immunity, and AI-driven models to predict outbreak hotspots using climate, migration, and farming data.

Policy-wise, there is growing consensus on the need for a One Health approach—integrating human, animal, and environmental health sectors—to combat zoonotic diseases like avian influenza. International funding mechanisms, such as the Global Health Security Agenda, support capacity building in vulnerable regions to strengthen early warning systems and laboratory diagnostics.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can bird flu be cured naturally?

- No, there is no proven natural cure for bird flu. Supportive care and antiviral medications are essential for recovery, especially in severe cases.

- Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

- There is no widely available commercial vaccine, but pre-pandemic vaccines for H5N1 and H7N9 exist in stockpiles for emergency use.

- How do you protect your chickens from bird flu?

- Implement strict biosecurity: limit visitors, disinfect equipment, avoid contact with wild birds, and monitor flocks for illness.

- Can humans get bird flu from eating eggs?

- No, if eggs are thoroughly cooked (no runny yolks or whites), the virus is destroyed and poses no risk.

- What should I do if I find dead wild birds?

- Do not touch them. Report the sighting to local wildlife or agricultural authorities for testing.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4