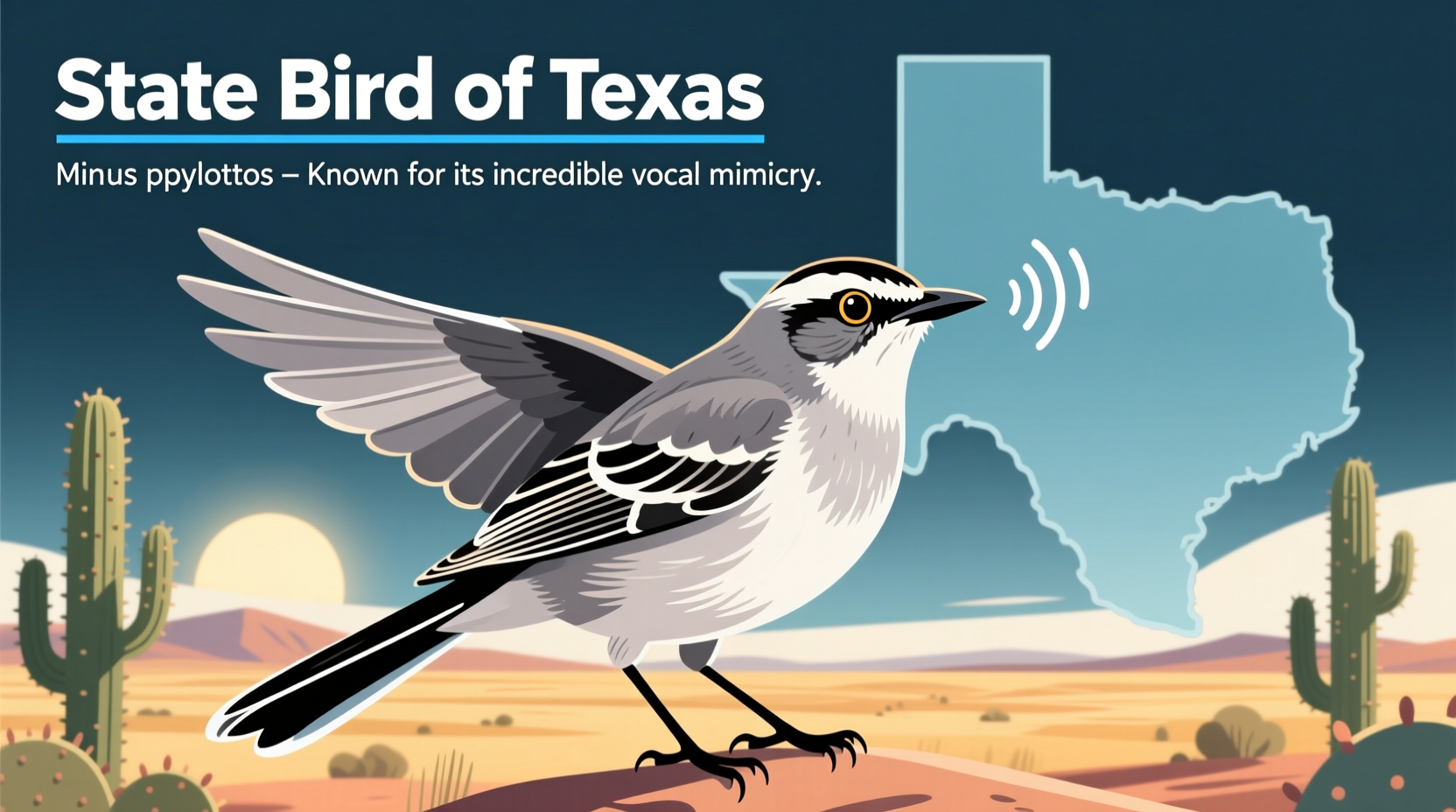

The official state bird of Texas is the Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos). Designated in 1927, this intelligent and vocal songbird has become a beloved symbol of Texan identity, frequently celebrated for its adaptability, complex melodies, and fearless defense of its territory. When searching for information about what is the state bird in Texas, many discover not only the official designation but also the deep cultural and ecological roots the mockingbird holds across the Lone Star State.

Historical Background: How the Northern Mockingbird Became Texas's Symbol

The journey to select an official state bird began in the early 20th century as part of a broader national movement to adopt state symbols that reflected regional pride and natural heritage. In Texas, schoolchildren played a pivotal role in the decision-making process. Organized by the Texas Federation of Women’s Clubs and supported by educators, a statewide vote among students was conducted to choose a representative bird.

Among the contenders were the Northern Cardinal, the Bobwhite Quail, and the Mockingbird. The Northern Mockingbird emerged as the overwhelming favorite. Its widespread presence across both rural and urban areas of Texas, combined with its remarkable singing ability, made it a natural choice. On January 31, 1927, the Texas Legislature officially adopted the Northern Mockingbird as the state bird through House Concurrent Resolution No. 13.

This decision aligned with similar choices in other southern states—Florida, Mississippi, and Tennessee also honor the mockingbird as their state bird—highlighting its symbolic resonance throughout the American South.

Biological Profile: Understanding the Northern Mockingbird

Beyond its symbolic status, the Northern Mockingbird is a fascinating species from a biological perspective. Here are key characteristics that define this avian icon:

- Scientific Name: Mimus polyglottos (meaning "many-tongued mimic")

- Length: 8–11 inches (20–28 cm)

- Wingspan: 12–15 inches (30–38 cm)

- Weight: 1.6–2.0 ounces (45–58 grams)

- Lifespan: Up to 8 years in the wild, though some individuals live over 14 years

- Diet: Omnivorous—feeds on insects, berries, seeds, and fruit

- Habitat: Open areas with sparse vegetation, suburban lawns, parks, and gardens

The mockingbird is non-migratory across much of its range, including Texas, meaning it can be observed year-round. It is especially common in central and southern regions of the state, where mild winters and abundant food sources support stable populations.

Vocal Mastery: Why the Mockingbird Sings So Much

One of the most distinctive traits of the Northern Mockingbird is its extraordinary vocal repertoire. Males, in particular, can sing more than 200 different songs, mimicking not only other birds—such as cardinals, jays, and thrashers—but also mechanical sounds like car alarms, barking dogs, and even cell phone ringtones.

This mimicry serves several purposes:

- Attracting mates during breeding season (March to July)

- Establishing and defending territory

- Communicating with nearby birds and offspring

Singing often occurs at night, especially under bright moonlight or artificial lighting, which can lead to occasional complaints from residents. However, this behavior underscores the bird’s adaptability to human environments.

Cultural Significance of the Mockingbird in Texas

The Northern Mockingbird holds a revered place in Texan culture, extending beyond its official status. It appears on state highway signs, university logos, and local sports team emblems. For example, the University of Houston’s mascot is “Shasta,” a costumed mockingbird, reflecting school pride and regional identity.

In literature and music, the mockingbird symbolizes vigilance, creativity, and resilience. Harper Lee’s novel To Kill a Mockingbird, while set in Alabama, reinforced the bird’s association with innocence and moral integrity—a theme that resonates across Southern culture, including Texas.

Folklore surrounding the bird includes beliefs such as:

- Killing a mockingbird brings bad luck

- Hearing a mockingbird sing at dawn signifies good fortune

- Its presence near a home offers protection

These traditions, passed down through generations, contribute to the bird’s enduring popularity and protected status in public consciousness—even though actual legal protections come from federal laws like the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.

Where and When to See the State Bird of Texas

For birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts interested in observing the Northern Mockingbird in its natural habitat, Texas offers excellent opportunities throughout the year. Unlike seasonal migrants, the mockingbird remains active and visible in all months, making it one of the most reliably spotted birds in the state.

Best Locations for Observing Mockingbirds

Because mockingbirds thrive in semi-open habitats, they are commonly found in:

- Urban backyards and residential neighborhoods

- Parks and golf courses

- Agricultural fields and fence lines

- Coastal scrublands and brushy areas

Some recommended birding hotspots include:

- Zilker Park (Austin)

- Hermann Park (Houston)

- Fort Worth Nature Center & Refuge

- Big Thicket National Preserve

- South Padre Island Birding Centers

Optimal Times for Observation

Morning hours (dawn to mid-morning) are ideal for hearing mockingbird songs and watching foraging behavior. During breeding season (spring and early summer), males are especially vocal and territorial, often seen perched prominently on rooftops, power lines, or treetops.

Nighttime singing, while less common, may occur in well-lit urban areas. This behavior does not indicate distress but rather reflects the bird’s response to environmental stimuli.

| Season | Behavior | Best Viewing Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Spring (Mar–May) | Singing, mating, nest-building | Listen for complex songs at dawn |

| Summer (Jun–Aug) | Feeding young, defending territory | Watch for dive-bombing if near nests |

| Fall (Sep–Nov) | Foraging for berries, quieter | Look in berry-producing shrubs |

| Winter (Dec–Feb) | Year-round resident, less vocal | Spot them on open lawns hunting insects |

How to Attract Mockingbirds to Your Yard

If you're hoping to welcome the Texas state bird into your own backyard, consider these practical tips:

- Plant Native Berry-Producing Shrubs: Firethorn, holly, mulberry, and yaupon holly provide essential winter food sources.

- Maintain Open Lawns: Mockingbirds prefer short grass for hunting insects like beetles, grasshoppers, and ants.

- Avoid Pesticides: Chemical treatments reduce insect availability, limiting natural food supplies.

- Provide Water Sources: A shallow birdbath or fountain encourages drinking and bathing.

- Limit Outdoor Cats: Domestic cats are leading predators of nesting birds; keeping them indoors protects mockingbird fledglings.

Note: Mockingbirds do not typically use bird feeders, so offering seed won’t attract them. Instead, focus on landscaping that supports their natural diet and nesting preferences.

Legal Protection and Conservation Status

The Northern Mockingbird is protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA), which makes it illegal to harm, capture, or possess the bird, its eggs, or its nests without a permit. While the species is currently listed as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), localized threats exist.

Primary concerns include:

- Habitat loss due to urban development

- Collisions with windows and vehicles

- Predation by domestic animals

- Pesticide exposure reducing insect prey

Despite these challenges, the mockingbird’s adaptability to human-altered landscapes has helped maintain strong population numbers in Texas. Citizen science projects like eBird and the Christmas Bird Count continue to monitor trends and inform conservation strategies.

Common Misconceptions About the Texas State Bird

Despite its fame, several myths persist about the Northern Mockingbird:

- Myth: The mockingbird is a type of nightingale.

Fact: Though both are songbirds, they belong to different families. The nightingale is native to Europe and Asia, not North America. - Myth: Only male mockingbirds sing.

Fact: Females also sing, though less frequently and usually during nesting season. - Myth: Mockingbirds imitate sounds because they’re intelligent like parrots.

Fact: While clever, their mimicry is instinctive and tied to reproduction and territoriality, not cognitive imitation in the way parrots learn human speech. - Myth: It’s legal to keep a mockingbird as a pet.

Fact: Under the MBTA, it is illegal to own or cage native migratory birds in the U.S.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why did Texas choose the mockingbird as its state bird?

Texas chose the Northern Mockingbird in 1927 due to its widespread presence, beautiful song, and symbolic representation of resilience and vigilance. A student-led vote helped determine the final selection.

Can you hunt the state bird of Texas?

No. The Northern Mockingbird is protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Hunting, capturing, or harming the bird is illegal without a special permit.

Do mockingbirds migrate out of Texas?

Most mockingbirds in Texas are year-round residents and do not migrate. Some northern populations may move south during harsh winters, but within Texas, they remain active throughout the year.

What does a Texas state bird look like?

The Northern Mockingbird is gray above and pale below, with long tails and prominent white wing patches visible in flight. It has a slender black bill and dark eyes, often appearing alert and upright when perched.

Are there any other state symbols related to the mockingbird in Texas?

No other official state symbols directly reference the mockingbird, but its image appears informally on various civic and educational insignias. The state flower is the bluebonnet, and the state mammal is the nine-banded armadillo.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4