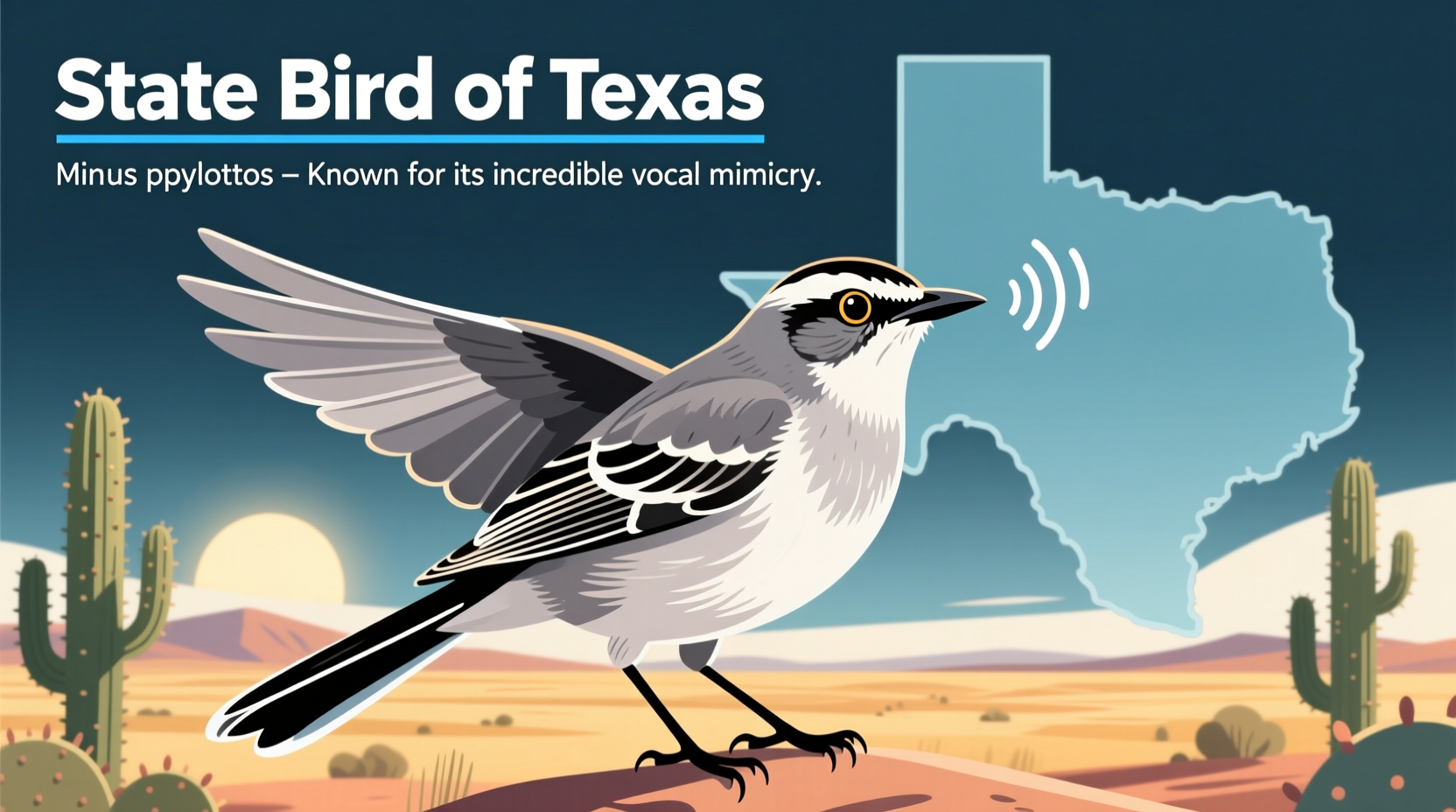

The state bird of Texas is the Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos). This iconic species was officially designated as the Lone Star State's avian symbol in 1927, chosen for its bold personality, remarkable vocal abilities, and year-round presence across Texas landscapes. Known for its fearless defense of territory and intricate songsâoften mimicking other birds, animals, and even mechanical soundsâthe Northern Mockingbird has become a beloved emblem of Texan identity and natural heritage. As one of the most frequently searched topics in regional ornithology, “what is the state bird of texas” leads many to explore not only its official status but also its biological traits, cultural significance, and role in local ecosystems.

Historical Background: How the Northern Mockingbird Became Texasâs Symbol

The selection of the Northern Mockingbird as Texasâs state bird was not arbitrary. In the early 20th century, states across the U.S. began adopting official symbols to foster regional pride and environmental awareness. The Texas Legislature turned to the Texas State Library and Archives Commission and various womenâs organizations, particularly the Texas Federation of Womenâs Clubs (TFWC), to recommend suitable candidates.

After extensive deliberation, the Northern Mockingbird emerged as the top choice over contenders like the Northern Cardinal and the Roadrunner. On January 31, 1927, House Concurrent Resolution No. 14 formally adopted the bird as the official state symbol. The resolution praised the mockingbird for its âdevotion to family,â âfearless protection of its nest,â and âbeautiful music,â all qualities seen as reflective of Texan values.

Biological Profile: Understanding Mimus polyglottos

The Northern Mockingbird belongs to the family Mimidae, known for their vocal mimicry and complex behaviors. Here are key biological characteristics that distinguish this species:

- Size and Appearance: Approximately 8â10 inches long with a wingspan of 12â15 inches. It has gray upperparts, white underparts, and distinctive white wing patches visible in flight.

- Vocal Ability: Males can learn up to 200 different phrases, repeating each several times before switching. Songs may continue through the night, especially during breeding season or under artificial light.

- Habitat Range: Found throughout North America, from southern Canada to Mexico, but most abundant in open habitats with scattered trees and shrubsâcommon in suburban yards, parks, and agricultural areas in Texas. \li>Diet: Omnivorous; feeds on insects (beetles, grasshoppers, spiders), earthworms, berries, and fruits. Diet shifts seasonally, with more insects consumed in spring and summer.

- Lifespan: Average lifespan is 8 years in the wild, though some individuals live over a decade.

Why Was the Mockingbird Chosen Over Other Birds?

Several factors contributed to the Northern Mockingbirdâs selection as Texasâs state bird:

- Resilience and Adaptability: Unlike migratory species, the mockingbird resides in Texas year-round, symbolizing endurance and loyalty to the land.

- Cultural Resonance: Its persistent singing and territorial behavior were interpreted as metaphors for independence and courageâtraits associated with Texas history.

- Ecological Benefit: By consuming large numbers of insect pests and dispersing seeds via fruit consumption, it plays a beneficial role in both rural and urban environments.

- Distinctive Behavior: Few birds match the mockingbirdâs ability to imitate sounds, making it a fascinating subject for birdwatchers and scientists alike.

Interestingly, while the Roadrunnerâa fast-running, ground-dwelling cuckooâwas a strong contender due to its Southwestern charm, it lacked the widespread distribution and vocal prominence that made the mockingbird more universally relatable across Texasâs diverse regions.

Geographic Distribution Across Texas

The Northern Mockingbird thrives in nearly every ecoregion of Texas, from the piney woods of East Texas to the arid deserts of West Texas. However, population density varies based on habitat availability:

| Ecoregion | Habitat Suitability | Common Nesting Sites |

|---|---|---|

| Coastal Prairies | High | Hedges, mesquite thickets, ornamental shrubs |

| Central Texas Hill Country | High | Live oak trees, rocky outcrops, fence lines |

| South Texas Plains | Moderate to High | Brushlands, huisache groves, urban gardens |

| Panhandle and High Plains | Moderate | Cottonwood stands, shelterbelts, farmsteads |

| Trans-Pecos Desert | Low to Moderate | Riparian zones, yucca clumps, developed oases |

This adaptability underscores why the bird remains a consistent presence in both rural and urban settings, increasing public familiarity and affection for the species.

Cultural Significance Beyond Statehood

The Northern Mockingbird extends beyond political symbolism into literature, music, and folklore. Harper Leeâs Pulitzer Prize-winning novel *To Kill a Mockingbird* (1960) uses the bird as a metaphor for innocence and moral integrity, reinforcing its image as a creature worthy of protection. Though set in Alabama, the novel resonated deeply across the South, including Texas, where educators often use it to discuss ethics and empathy.

In Native American traditions, particularly among the Caddo and Tonkawa tribes historically present in Texas, birds like the mockingbird were seen as messengers or trickstersâintelligent beings capable of bridging worlds. While not always central in myth, its voice was sometimes interpreted as a warning or call to attention.

Today, the mockingbird appears on Texas license plates, school insignias, and sports team logos, including minor league baseball teams such as the San Antonio Missions (formerly nicknamed the “Mockingbirds”). Its silhouette is occasionally used in branding for eco-tourism and wildlife conservation campaigns.

Observing the State Bird: Tips for Birdwatchers

If youâre interested in spotting or attracting Northern Mockingbirds in Texas, consider these practical tips:

- Best Time to Observe: Early morning and late afternoon, especially during breeding season (MarchâJuly), when males sing persistently to defend territory and attract mates.

- Listen for Imitations: Learn to recognize common mimicked species such as cardinals, blue jays, cat calls, and even car alarms. Use apps like Merlin Bird ID or Audubon Bird Guide to compare recordings.

- Create a Mockingbird-Friendly Yard: Plant native berry-producing shrubs like yaupon holly, sumac, and agarita. Avoid excessive pesticide use to maintain insect populations.

- Provide Water Sources: A shallow birdbath or fountain encourages bathing and drinking, especially in hot summers.

- Nesting Support: While they donât use birdhouses, dense shrubs and thorny bushes (like rose bushes or cacti) offer ideal nesting sites.

Keep in mind that mockingbirds can be aggressive during nesting season, dive-bombing perceived threatsâincluding humans and pets. Respect their space to avoid conflict and ensure successful fledging.

Conservation Status and Environmental Challenges

The Northern Mockingbird is currently listed as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), thanks to its wide distribution and stable population trends. However, localized declines have been noted in parts of the southern U.S., potentially linked to:

- Urban sprawl reducing green spaces

- Pesticide use diminishing insect prey

- Window collisions and outdoor cat predation

- Climate change affecting food availability and migration patterns of competing species

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) encourages citizens to participate in citizen science projects like the Christmas Bird Count and eBird to monitor populations and inform conservation strategies.

Common Misconceptions About the State Bird

Despite its fame, several myths persist about the Northern Mockingbird:

- Myth: It only sings at night.

Fact: While males may sing nocturnally (especially young, unmated ones), daytime singing is far more common. - Myth: Itâs protected solely because itâs the state bird.

Fact: All native birds, including mockingbirds, are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, making it illegal to harm them or destroy nests without a permit. - Myth: Itâs closely related to thrushes or starlings.

Fact: Itâs part of the Mimidae family, which includes thrashers and tremblers, not closely related to true thrushes (Turdidae) or starlings (Sturnidae).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- When did Texas adopt the Northern Mockingbird as its state bird?

- Texas officially adopted the Northern Mockingbird as its state bird on January 31, 1927, via legislative resolution.

- Can Northern Mockingbirds really mimic human-made sounds?

- Yes, they frequently imitate car alarms, cell phone ringtones, chainsaws, and other mechanical noises, especially in urban environments.

- Is it legal to keep a Northern Mockingbird as a pet?

- No. Under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, it is illegal to capture, possess, or sell native birds like the Northern Mockingbird without special permits.

- Do female Northern Mockingbirds sing?

- Traditionally thought to be primarily male singers, recent studies show that females also sing, particularly during winter and in defending territory.

- Are there any other states that have the Northern Mockingbird as their state bird?

- Yes. Besides Texas, the Northern Mockingbird is also the state bird of Arkansas, Florida, Mississippi, and Tennessee.

In summary, the answer to “what is the state bird of texas” is the Northern Mockingbirdâa species celebrated for its intelligence, song, and symbolic strength. Whether viewed through a biological, historical, or cultural lens, this bird continues to captivate residents and visitors alike, serving as a living emblem of Texasâs rich natural legacy.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4