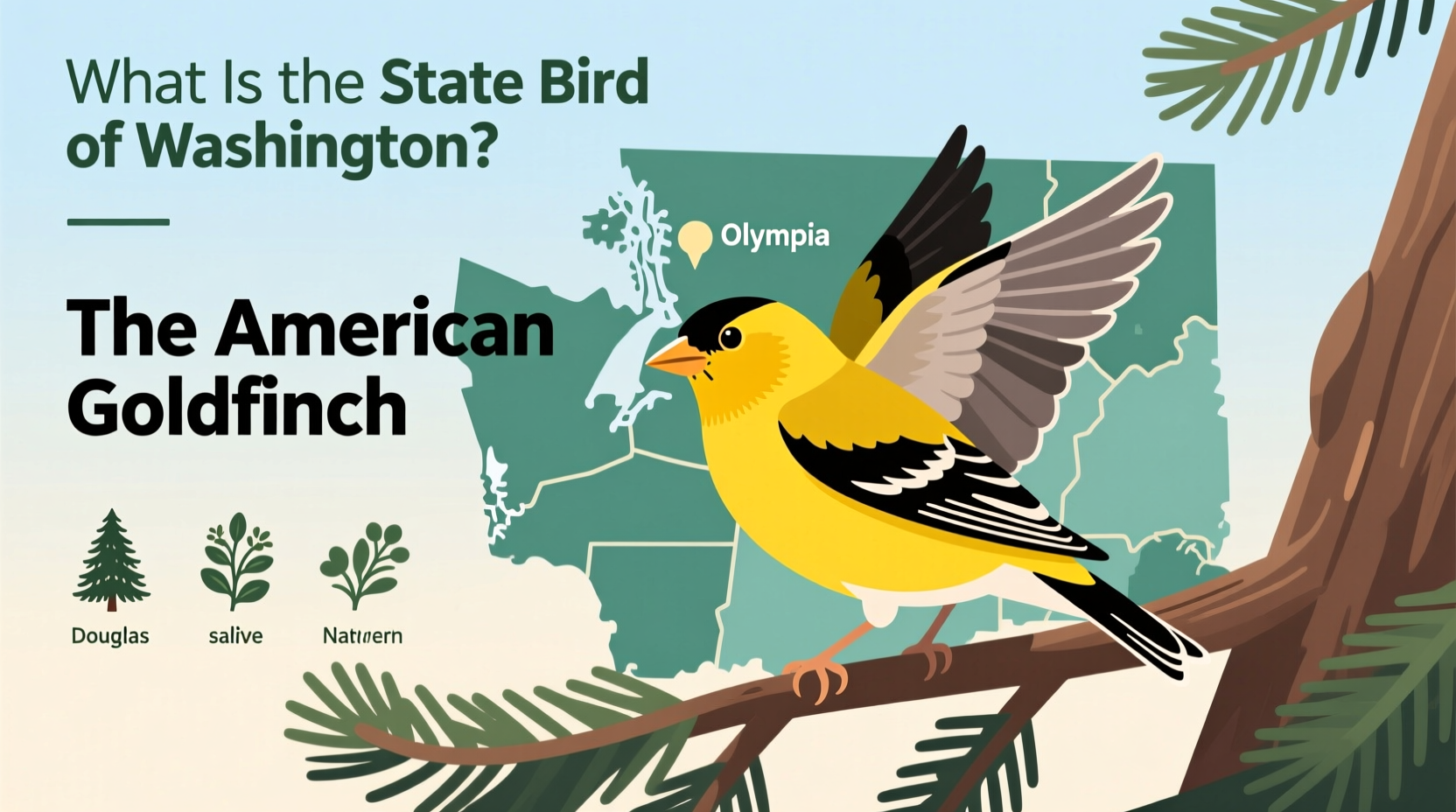

The state bird of Washington is the American Goldfinch (Spiune tristis), a vibrant yellow songbird known for its cheerful call and seasonal plumage changes. Officially adopted in 1951, the American Goldfinch stands out as a symbol of natural beauty and resilience across the Pacific Northwest. This designation reflects both the bird’s widespread presence throughout Washington state and its cultural resonance among residents who value native wildlife. As one of the most frequently searched avian symbols in the region, queries like 'what is the state bird of Washington' often lead to deeper interest in its ecological habits, migratory patterns, and significance in local traditions.

History and Official Designation

The American Goldfinch became the official state bird of Washington on April 17, 1951, replacing the Willow Goldfinch—a subspecies later classified under the broader American Goldfinch category due to taxonomic revisions. The decision followed a campaign led by schoolchildren and supported by ornithological societies, emphasizing the bird's year-round visibility and aesthetic appeal. Unlike states that chose birds based solely on historical figures or events, Washington selected its emblem based on accessibility and public affection.

Prior to 1951, there was no official state bird, though several species were informally celebrated in regional art and literature. The push for formal recognition gained momentum during mid-20th-century conservation movements, which encouraged civic engagement with native species. The legislative process involved consultation with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and input from educators, ensuring the choice aligned with educational goals and environmental awareness.

Biological Characteristics of the American Goldfinch

Spiune tristis, commonly known as the American Goldfinch, belongs to the finch family (Fringillidae). It measures approximately 4.3–5.1 inches in length with a wingspan of 7.5–8.7 inches and weighs between 0.4 and 0.7 ounces. Males display bright lemon-yellow feathers during breeding season, accented by black foreheads and wings with white markings. Females are more subdued, exhibiting olive-yellow tones.

One distinguishing biological trait is their strict vegetarian diet. Unlike many songbirds that consume insects during nesting, goldfinches primarily eat seeds—especially those from thistles, sunflowers, and asters. Their conical beaks are specially adapted for extracting seeds from plant heads, making them frequent visitors to backyard feeders stocked with nyjer (thistle) seed.

Another unique feature is their late breeding cycle. While most birds begin nesting in spring, American Goldfinches typically start in late June or July. This timing coincides with peak seed production in their preferred food plants, ensuring ample nutrition for hatchlings.

Habitat and Distribution Across Washington

The American Goldfinch thrives in open habitats such as meadows, prairies, orchards, and suburban gardens—environments abundant throughout Washington. They are non-migratory in western parts of the state but may move southward or to lower elevations during harsh winters in eastern regions. Their adaptability to human-modified landscapes has contributed to stable population numbers despite urban development.

In Puget Sound lowlands, they're commonly seen in parks and residential areas with native flowering plants. In contrast, in the drier shrub-steppe zones east of the Cascades, they rely on riparian corridors and agricultural edges. Conservation efforts focused on preserving native flora directly benefit this species by maintaining food sources and nesting sites.

| Feature | American Goldfinch Details |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Spiune tristis |

| Length | 4.3–5.1 inches |

| Wingspan | 7.5–8.7 inches |

| Diet | Seeds (especially thistle, sunflower) |

| Nesting Season | Late June to August |

| Conservation Status | Least Concern (IUCN) |

Cultural and Symbolic Significance

Beyond its official status, the American Goldfinch carries rich symbolic meaning in Washington’s cultural landscape. Its bright coloration evokes joy, renewal, and endurance—qualities often associated with the state’s natural environment. Indigenous communities in the region have long recognized small songbirds as messengers or indicators of seasonal change, although specific legends about the goldfinch vary among tribes.

In contemporary settings, the bird appears in school curricula, state tourism materials, and environmental education programs. Artists and poets use its image to represent hope and simplicity. Moreover, because it remains visible through much of the year, especially at feeders, it fosters personal connections between people and nature—an essential aspect of urban ecology initiatives.

How to Attract American Goldfinches to Your Yard

For bird enthusiasts wondering how to observe the state bird up close, creating a goldfinch-friendly garden is both practical and rewarding. Here are actionable tips:

- Install Nyjer Feeders: Use mesh or tube feeders designed for fine seeds. These mimic natural feeding behaviors and reduce waste.

- Plant Native Seed-Bearing Flowers: Include purple coneflower, black-eyed Susan, milkweed, and native thistles. These provide natural food sources and support pollinators.

- Provide Water Sources: A shallow birdbath with gently sloping edges encourages bathing and drinking, particularly during dry summers.

- Avoid Pesticides: Chemical treatments reduce insect populations and contaminate seeds, indirectly affecting bird health.

- Offer Nesting Materials: In spring, hang small bundles of natural fibers (like cotton or pet fur) in trees to assist nest construction.

Maintaining clean feeders is crucial; moldy nyjer can cause illness. Clean feeders every two weeks with a mild bleach solution (one part bleach to nine parts water), rinsing thoroughly before reuse.

Common Misconceptions About the State Bird

Despite its popularity, several misconceptions persist about Washington’s state bird. One common error is confusing the American Goldfinch with the Western Meadowlark, which is South Dakota’s state bird and sometimes mistaken due to similar coloring. Another misconception involves migration: while some individuals move seasonally, many Washington populations remain resident year-round, especially in milder coastal climates.

Additionally, people often assume all yellow birds are male goldfinches. However, females in winter plumage appear dull greenish-yellow and can be difficult to distinguish without careful observation. Juveniles resemble females but have streaked backs and less defined facial patterns.

Role in Education and Citizen Science

The American Goldfinch plays an important role in science education and community-based monitoring. Programs like the Great Backyard Bird Count (GBBC) and eBird regularly record sightings across Washington, helping researchers track population trends and habitat use. Schools incorporate the state bird into life science units, teaching students about adaptation, classification, and ecosystems.

Teachers can enhance learning by organizing classroom birdwatching sessions, building simple feeders, or participating in Project FeederWatch, a winter-long survey run by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. These activities promote scientific literacy while fostering stewardship values.

Comparative Look: Other State Birds in the Pacific Northwest

Washington’s choice of the American Goldfinch contrasts with neighboring states’ selections. Oregon designated the Western Meadowlark in 1927, valuing its melodious song. Idaho chose the Mountain Bluebird in 1931 for its striking blue plumage and association with open country. British Columbia, though not a U.S. state, named the Steller’s Jay as its provincial bird, reflecting forested mountain environments.

Unlike these choices, the American Goldfinch emphasizes subtlety and accessibility over grandeur. It does not require remote wilderness to be observed, making it ideal for inclusive engagement across age groups and geographic settings.

Threats and Conservation Outlook

Currently, the American Goldfinch is listed as “Least Concern” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), indicating stable global populations. However, localized threats exist. Habitat fragmentation, loss of native plants, and climate-driven shifts in flowering times could disrupt food availability. Window collisions and domestic cat predation also contribute to mortality rates.

To mitigate risks, conservationists recommend planting diverse native vegetation, using window decals to prevent strikes, and keeping cats indoors. Supporting land trusts and participating in habitat restoration projects further strengthens ecosystem resilience.

FAQs About Washington’s State Bird

- Why did Washington choose the American Goldfinch as its state bird?

- Washington selected the American Goldfinch in 1951 for its widespread presence, attractive appearance, and public popularity, especially among schoolchildren who advocated for its adoption.

- Do American Goldfinches migrate from Washington?

- Some do, particularly in colder eastern parts of the state, but many remain year-round, especially in western Washington where winters are milder.

- What kind of feeder attracts American Goldfinches?

- Tube or mesh feeders filled with nyjer (thistle) seed are most effective, as they match the bird’s feeding behavior and dietary preferences.

- Can you keep an American Goldfinch as a pet?

- No. It is illegal under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act to capture, possess, or sell native wild birds without federal permits.

- How can I tell a female American Goldfinch from a juvenile?

- Females lack strong markings but have smooth plumage. Juveniles show streaking on the back and breast, with paler bills compared to adults.

In summary, the American Goldfinch embodies the spirit of Washington through its resilience, beauty, and everyday presence in both rural and urban environments. Whether viewed through a biological, cultural, or ecological lens, this small songbird continues to inspire curiosity and conservation action. For anyone asking 'what is the state bird of Washington,' the answer opens a doorway to broader understanding of regional biodiversity and our shared responsibility to protect it.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4