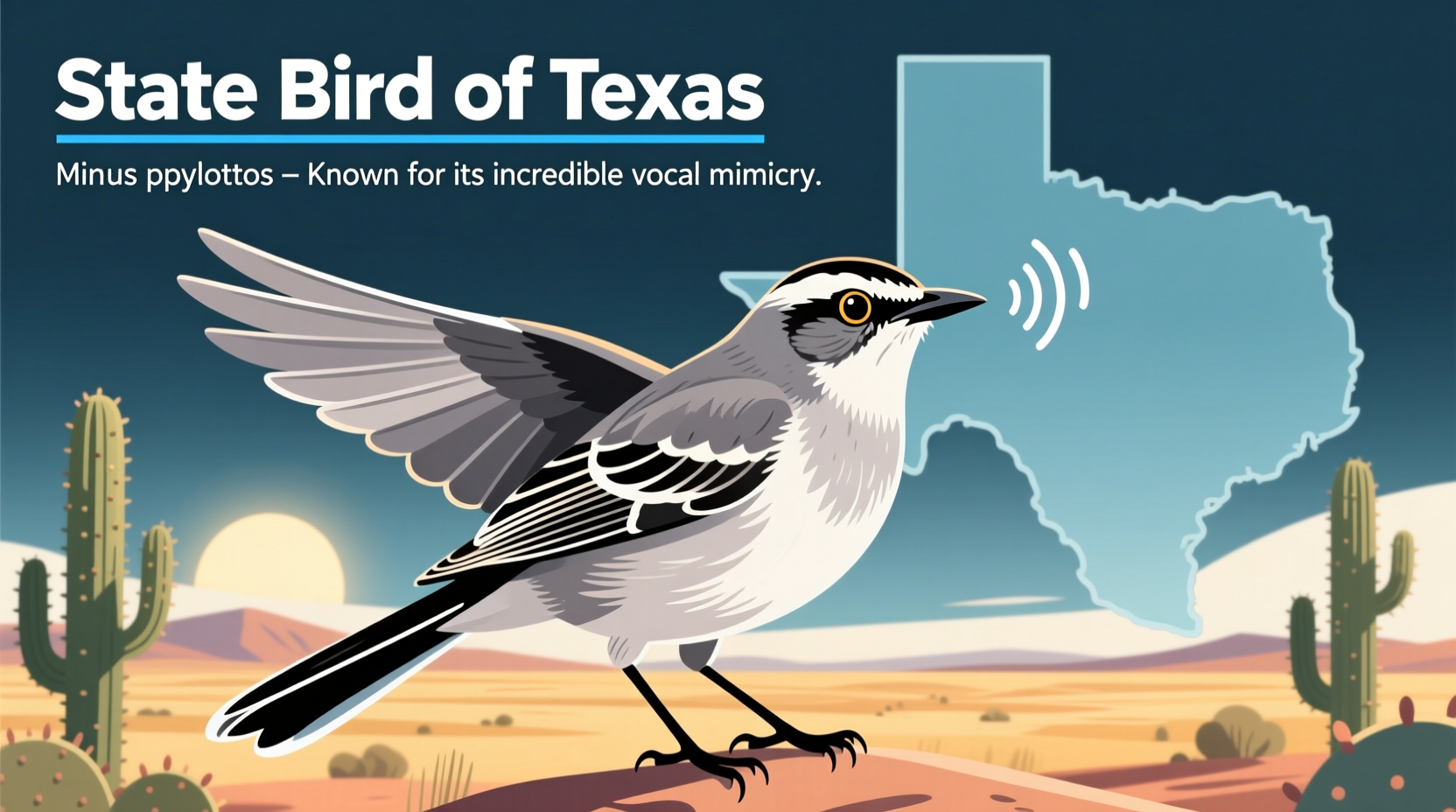

The official state bird of Texas is the Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos), a highly intelligent and melodious songbird celebrated for its remarkable ability to mimic a wide range of sounds. Chosen for its bold personality, adaptability, and enchanting songs, the Northern Mockingbird was officially designated as the state bird in 1927 by the Texas Legislature. This selection reflects both the bird's widespread presence throughout Texas and its deep cultural resonance with Texan identity. As one of the most frequently searched topics related to regional wildlife, understanding what is the state of Texas bird reveals not only biological significance but also historical and symbolic importance.

History and Official Designation

The journey to selecting the Northern Mockingbird as Texas’s state symbol began in the early 20th century, during a broader movement across American states to adopt official emblems representing their unique natural heritage. In 1927, after careful deliberation by schoolchildren, ornithologists, and civic groups, the Texas Legislature formally adopted the Northern Mockingbird through House Concurrent Resolution No. 14. It replaced no prior official bird, as Texas had not previously recognized one.

The decision was influenced heavily by the bird’s ubiquity across urban, suburban, and rural landscapes in Texas. Unlike many birds that migrate seasonally, the mockingbird is a permanent resident, seen year-round from El Paso to Houston. Its fearless defense of nests and territory also resonated with the independent spirit associated with Texas culture. The resolution highlighted the bird’s musical repertoire and usefulness in controlling insect populations, further solidifying its status as a fitting representative of the state.

Biological Profile: What Makes the Northern Mockingbird Unique?

The Northern Mockingbird belongs to the family Mimidae, which includes thrashers and catbirds, all known for their complex vocalizations. Adults typically measure 8–10 inches in length, with a wingspan of about 12–15 inches. They have gray upperparts, pale underbellies, long tails with white outer feathers, and distinctive white wing patches visible in flight.

One of the most extraordinary traits of this species is its vocal mimicry. A single mockingbird can imitate over 35 different bird species, as well as environmental sounds like car alarms, barking dogs, and even human-made noises. Males are especially vocal, often singing at night during breeding season to attract mates or defend territory. Their songs consist of repeated phrases, each delivered 2–6 times before transitioning to the next sound.

These birds are omnivorous, feeding on insects (such as beetles, grasshoppers, and spiders) during warmer months and switching to berries and fruits in winter. They are commonly found in open habitats including parks, gardens, backyards, and forest edges—making them easily observable by amateur birdwatchers.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance

Beyond its biological attributes, the Northern Mockingbird holds profound cultural symbolism in Texas and beyond. It appears on the state quarter released in 2004 as part of the U.S. Mint’s 50 State Quarters Program, depicted perched on a cactus—a nod to its resilience in arid environments. The bird has also been featured in literature, music, and art, most famously in Harper Lee’s novel To Kill a Mockingbird, where it symbolizes innocence and moral integrity.

In Texan folklore, the mockingbird is admired for its courage and tenacity. Despite its small size, it fearlessly dives at much larger animals—including cats, hawks, and humans—that approach its nest. This protective instinct aligns with values of bravery and loyalty cherished in Texan identity. Additionally, because it sings throughout the day and sometimes into the night, the mockingbird is often associated with vigilance and perseverance.

The choice of the mockingbird over other contenders such as the Northern Cardinal or the Scissor-tailed Flycatcher underscores a preference for native, resilient species deeply embedded in local ecosystems. While some states chose colorful or rare birds, Texas opted for one that is accessible, familiar, and acoustically impressive—an everyday ambassador of nature.

Where and When to See the State Bird of Texas

For birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts interested in observing the Northern Mockingbird in its natural habitat, timing and location are key. The bird is non-migratory and present in Texas all year, making it possible to spot at any time. However, spring and early summer (March through July) offer the best opportunities to hear males sing vigorously during courtship and nesting seasons.

Ideal viewing locations include:

- Urban parks: Zilker Park (Austin), Hermann Park (Houston), Fort Worth Botanic Garden

- Nature preserves: Balcones Canyonlands National Wildlife Refuge, Attwater Prairie Chicken Preserve

- Backyard feeders: Especially those offering suet, mealworms, or fruit like mulberries and hackberries

Early morning hours (dawn to mid-morning) are optimal for hearing song activity. Look for mockingbirds perched conspicuously on fence posts, rooftops, or treetops, where they perform their vocal displays. During winter, they may be seen foraging low to the ground in leaf litter or shrubs.

Conservation Status and Environmental Role

The Northern Mockingbird is currently listed as a species of Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Populations remain stable across its range, including Texas, thanks to its adaptability to human-altered landscapes. However, localized declines have been noted in areas experiencing rapid urbanization, pesticide use, and habitat fragmentation.

As an insectivore, the mockingbird plays a vital role in natural pest control, consuming large quantities of harmful insects. Its seed-dispersal behavior also contributes to plant regeneration, particularly in disturbed or recovering ecosystems. Protecting green spaces, limiting chemical pesticide application, and preserving native vegetation support healthy mockingbird populations.

Citizens can contribute to conservation efforts by participating in citizen science projects such as eBird or the Great Backyard Bird Count, reporting sightings and helping track population trends. Installing native plants like yaupon holly, sumac, and agarita provides food and shelter, enhancing backyard habitats for these birds.

Common Misconceptions About the State Bird

Despite its popularity, several misconceptions surround the Northern Mockingbird:

- Misconception 1: It’s illegal to kill a mockingbird anywhere in Texas.

Reality: While killing any migratory bird without a permit violates the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, there is no specific Texas law solely protecting the mockingbird beyond this. Enforcement applies to all protected species equally. - Misconception 2: The mockingbird mimics only birds.

Reality: These birds copy mechanical sounds, frogs, crickets, and even cell phone ringtones—demonstrating advanced auditory learning. - Misconception 3: All mockingbirds sing constantly.

Reality: Only unmated males sing extensively at night; females and paired males are generally quieter.

Comparison With Other State Birds

Texas is not alone in honoring the Northern Mockingbird—five states total have adopted it as their official bird: Texas, Arkansas, Florida, Mississippi, and Tennessee. This makes it the most widely shared state bird in the U.S., reflecting its broad appeal and distribution across the South.

Compared to other state birds like the California Quail or the Baltimore Oriole, the mockingbird stands out for its intelligence, adaptability, and accessibility. While some state birds are seasonal or restricted to remote habitats, the mockingbird thrives alongside people, making it a democratic symbol available to all citizens regardless of geography.

| State | State Bird | Year Adopted |

|---|---|---|

| Texas | Northern Mockingbird | 1927 |

| Arkansas | Northern Mockingbird | 1929 |

| Florida | Northern Mockingbird | 1927 |

| Mississippi | Northern Mockingbird | 1944 |

| Tennessee | Northern Mockingbird | 1933 |

Tips for Attracting Mockingbirds to Your Yard

If you want to observe the state bird up close, consider creating a welcoming environment:

- Plant native berry-producing shrubs: Yaupon holly, eastern red cedar, and sumac provide essential winter food sources.

- Avoid chemical pesticides: These reduce insect availability, a primary food source during breeding season.

- Provide water: A shallow birdbath or fountain encourages drinking and bathing, especially in hot Texas summers.

- Limit outdoor cats: Free-roaming felines pose a major threat to nesting birds.

- Preserve open perching sites: Fences, dead branches, and utility wires serve as singing posts and lookout points.

Keep in mind that mockingbirds can be territorial, especially during nesting season (April–August). They may dive at perceived threats near their nests. If this occurs, temporarily avoid the area or install temporary visual barriers to reduce conflict.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Why did Texas choose the Northern Mockingbird as its state bird?

- Texas chose the Northern Mockingbird in 1927 for its beautiful song, year-round presence, and fearless character, which reflect Texan values of independence and resilience.

- Can you hunt or kill a mockingbird in Texas?

- No. The Northern Mockingbird is protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act, making it illegal to harm, capture, or kill the bird without a special permit.

- Do all parts of Texas have mockingbirds?

- Yes. The Northern Mockingbird is found statewide, from the Panhandle to the Rio Grande Valley, in both rural and urban environments.

- How can I tell a mockingbird apart from similar birds?

- Look for gray plumage, long tail, white wing patches visible in flight, and bold behavior. Its habit of flicking wings open while walking and repeating phrases in song are distinctive clues.

- Is the mockingbird the only state symbol in Texas?

- No. Texas also has a state flower (bluebonnet), state tree (pecan), state mammal (nine-banded armadillo), and state flying mammal (Mexican free-tailed bat), among others.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4