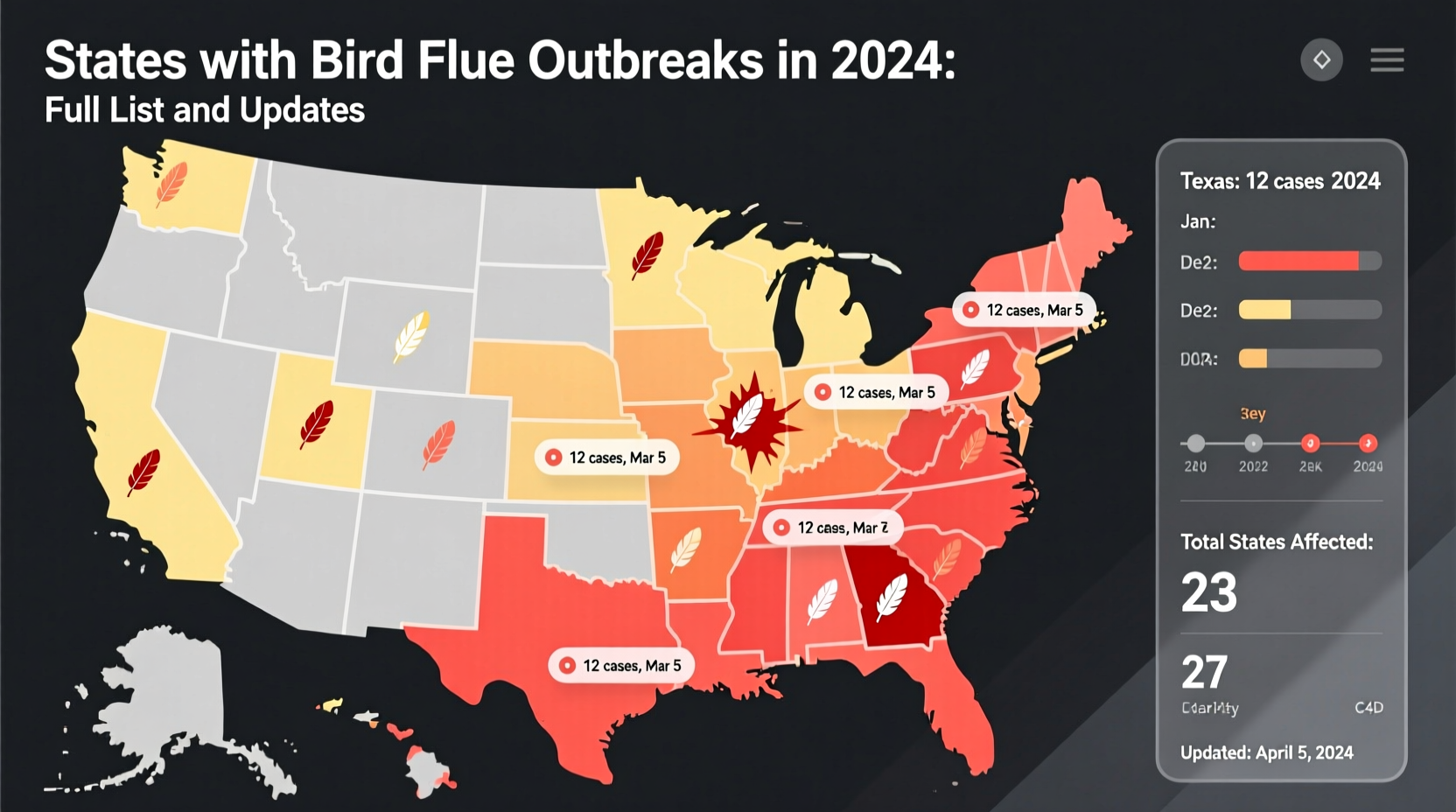

Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, has been detected in multiple U.S. states across both commercial and backyard poultry flocks, as well as in wild bird populations. As of the most recent data in 2024, confirmed cases of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) have been reported in over 40 states, including but not limited to Texas, California, Iowa, Minnesota, Kansas, Nebraska, Wisconsin, Indiana, Ohio, North Carolina, Missouri, and Colorado. The spread of bird flu across these states underscores the importance of monitoring local agricultural updates, especially for backyard bird owners, poultry farmers, and wildlife observers. A natural longtail keyword variant such as 'which U.S. states currently have bird flu outbreaks' is critical for those seeking real-time information on regional risks and containment measures.

Understanding Bird Flu: A Biological Overview

Bird flu is caused by type A strains of the influenza virus, primarily affecting birds—both domestic and wild. The most concerning strain in recent years has been H5N1, a highly pathogenic variant that can spread rapidly among bird populations and, in rare cases, transmit to humans. This virus spreads through direct contact with infected birds, their droppings, or contaminated surfaces and equipment. While the primary hosts are poultry and migratory waterfowl such as ducks and geese, the virus has also been found in raptors, seabirds, and even some mammalian species like foxes and skunks that have scavenged infected birds.

The biology of avian influenza makes it particularly challenging to contain. Wild birds, especially those on major migration routes like the Mississippi Flyway and the Pacific Flyway, play a significant role in spreading the virus across state lines. For example, states along the Central Flyway—such as Kansas, Nebraska, and the Dakotas—have seen recurring outbreaks during spring and fall migrations when infected birds travel through shared stopover sites.

Current States Affected by Bird Flu in 2024

As of mid-2024, bird flu activity remains widespread across the United States. According to surveillance data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the following states have reported active or recent cases:

| State | First Detected (Year) | Primary Species Affected | Status (2024) |

|---|---|---|---|

| California | 2022 | Backyard poultry, wild ducks | Active monitoring |

| Texas | 2022 | Commercial turkeys, geese | Outbreaks ongoing |

| Iowa | 2022 | Laying hens, turkeys | Containment zones active |

| Minnesota | 2022 | Ducks, gulls, raptors | Recurring seasonal cases |

| Kansas | 2023 | Backyard flocks, wild birds | Multiple detections |

| North Carolina | 2023 | Broiler chickens | Recent commercial outbreak |

| Colorado | 2023 | Raptors, waterfowl | Wildlife-focused alerts |

This table highlights the geographic breadth of the outbreak and the diversity of affected species. States with large poultry industries—like Iowa and North Carolina—are particularly vigilant due to economic implications. Meanwhile, western states such as California and Oregon see frequent spillover from wild bird populations using coastal wetlands as wintering grounds.

Historical Context and Recurring Patterns

Bird flu is not new to the U.S. The 2014–2015 outbreak was one of the most devastating, affecting 21 states and resulting in the loss of over 50 million birds. That epidemic primarily followed the Central and Mississippi flyways, much like the current wave. However, the 2022–2024 outbreaks have shown broader geographic reach and greater persistence, suggesting possible changes in viral evolution or environmental factors.

One key difference today is improved surveillance and reporting systems. The USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) now maintains an interactive map tracking confirmed cases by county, updated weekly. This allows farmers, veterinarians, and birdwatchers to stay informed about local risks. Historical patterns indicate that outbreaks peak during two main periods: late winter to early spring (February–April) and again in the fall (October–December), coinciding with bird migration.

How Bird Flu Spreads Across State Lines

The movement of infected birds—especially migratory species—is the primary driver of inter-state transmission. Ducks, geese, swans, and shorebirds often carry the virus without showing symptoms, making them silent vectors. When they land in wetlands, lakes, or agricultural areas, they shed the virus through feces and saliva, contaminating water sources and soil.

Human-assisted spread also plays a role. Contaminated equipment, clothing, or vehicles used between farms can introduce the virus to new locations. Additionally, the legal and illegal transport of live birds for sale or breeding increases risk. States with porous borders and shared ecosystems—such as those in the Great Lakes region—often experience synchronized outbreaks.

Impacts on Agriculture and Food Supply

The presence of bird flu in a state triggers immediate biosecurity responses. Infected flocks are depopulated to prevent further spread, which affects egg and turkey supplies. For example, Iowa—the top egg-producing state—has faced periodic shortages due to HPAI outbreaks. Consumers may notice higher egg prices during peak outbreak seasons.

Despite these disruptions, the USDA and FDA emphasize that properly cooked poultry and eggs remain safe to eat. There are no known cases of human infection from consuming commercially processed products. However, backyard flock owners should avoid consuming meat or eggs from sick or dead birds.

Public Health Considerations and Human Risk

While bird flu primarily affects avian species, there have been rare cases of human infection, typically among individuals with prolonged, unprotected exposure to infected birds. As of 2024, only a handful of human cases have been reported in the U.S., mostly mild and linked to occupational exposure (e.g., farm workers, veterinarians).

The CDC considers the general public risk to be low. Nevertheless, people who handle birds should wear gloves and masks, practice hand hygiene, and report any unusual bird deaths to local authorities. States like Texas and California have established hotlines for reporting sick or dead wild birds.

What Birdwatchers and Nature Enthusiasts Should Know

For birdwatchers, the presence of bird flu doesn’t mean avoiding nature—but it does require caution. Avoid touching sick or dead birds, and never attempt to rehabilitate them without proper training and permits. Use binoculars instead of approaching closely, and clean your gear (scopes, boots, feeders) regularly, especially after visiting wetlands or rural areas.

Some states have temporarily restricted access to certain wildlife refuges during peak outbreak periods. For instance, parts of the Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge Complex in California implemented visitor limitations in early 2024 to reduce disturbance and potential spread. Always check with state fish and wildlife agencies before planning trips.

Protecting Backyard Flocks: Practical Steps for Owners

If you keep chickens, ducks, or other poultry at home, proactive biosecurity is essential. Key steps include:

- Isolate new birds for at least 30 days before introducing them to your flock.

- Prevent wild birds from accessing feed and water sources—use covered containers.

- Avoid visiting other poultry farms or markets without changing clothes and shoes afterward.

- Report any sudden illness or unexplained deaths to your veterinarian or state animal health official.

- Register your flock with your state’s department of agriculture if required.

States like Pennsylvania and New York offer free biosecurity kits and educational resources for small-scale producers.

Regional Differences in Response and Reporting

Response strategies vary by state based on agricultural economy, wildlife density, and regulatory frameworks. For example:

- Iowa has aggressive testing protocols and compensation programs for depopulated flocks.

- California focuses on surveillance in both commercial operations and wild bird habitats.

- Maine and Vermont, while smaller producers, maintain strict movement controls during outbreak seasons.

These differences mean that the definition of “active outbreak” can vary—some states report every positive test, while others only declare emergencies when commercial farms are affected.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about avian influenza:

- Misconception: Bird flu is spreading easily among humans.

Reality: Human-to-human transmission has not been documented; infections are rare and usually linked to direct bird contact. - Misconception: All dead birds are signs of bird flu.

Reality: Many factors cause bird mortality; testing is needed for confirmation. - Misconception: Feeding wild birds spreads bird flu significantly.

Reality: While feeders can concentrate birds, the primary vector remains migratory waterfowl.

How to Stay Updated on Bird Flu Activity

To get accurate, up-to-date information, consult authoritative sources:

- USDA APHIS Avian Influenza website: https://www.aphis.usda.gov

- CDC Avian Influenza page: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/avian

- Your state’s department of agriculture or wildlife agency website

- Local extension offices affiliated with land-grant universities

Many states send email alerts or maintain social media updates during active outbreaks.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can I still go birdwatching if bird flu is present in my state?

Yes, but take precautions: avoid close contact with birds, do not touch sick or dead animals, and sanitize equipment after outings.

Are eggs and chicken safe to eat during a bird flu outbreak?

Yes. Commercially produced poultry and eggs are safe when properly cooked. The virus is destroyed by heat.

How can I report a sick or dead bird in my area?

Contact your state’s wildlife agency or use the USGS National Wildlife Health Center’s online reporting tool.

Does bird flu affect pets like cats or dogs?

Rare cases have occurred, especially in cats that hunt infected birds. Keep pets away from sick or dead wildlife.

Will bird flu ever be eradicated?

Complete eradication is unlikely due to its presence in wild bird populations. Ongoing surveillance and biosecurity are key to managing risks.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4