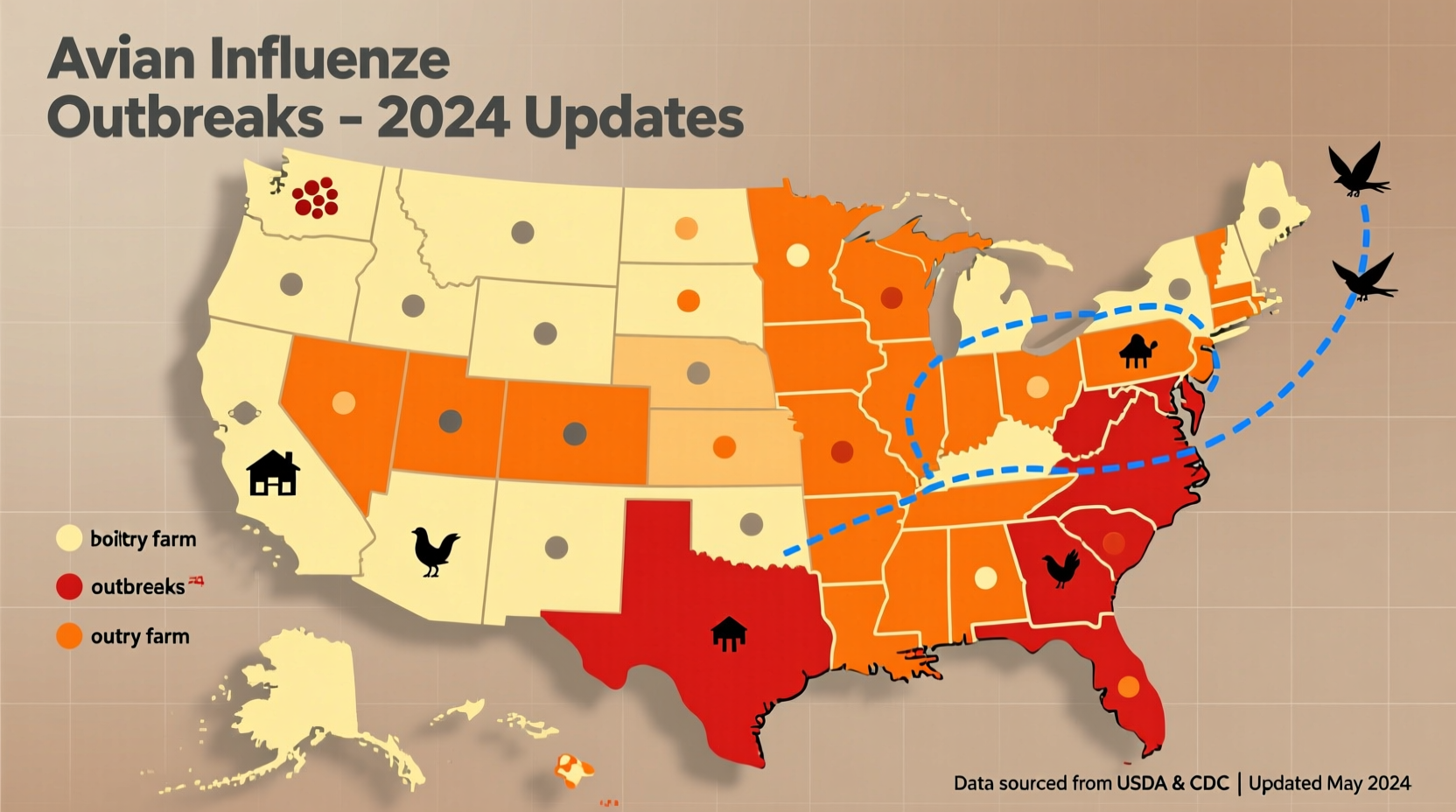

Several U.S. states have reported cases of bird flu in 2024, including confirmed outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 in both commercial poultry operations and wild bird populations. States with recent bird flu activity include California, Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Texas, and Wisconsin. Monitoring efforts by the USDA and state agricultural departments continue to track the spread of the virus, particularly among migratory bird populations and backyard flocks. For individuals searching for information on what states have the bird flu, it is essential to consult updated reports from official sources such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and state veterinary offices, as the situation evolves seasonally with bird migration patterns.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Types and Transmission

Bird flu, or avian influenza, refers to a group of viruses that primarily affect birds. These viruses are classified into two main categories based on their pathogenicity: low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) and highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). The H5N1 strain, which has been responsible for widespread outbreaks since 2022, falls under the HPAI category due to its high mortality rate in domestic poultry and potential spillover into mammals, including humans in rare cases.

The virus spreads through direct contact between infected and healthy birds, as well as through contaminated surfaces, water, feed, and equipment. Wild waterfowl—especially ducks, geese, and swans—are natural reservoirs of the virus and often carry it without showing symptoms. This makes them key vectors in spreading the disease across regions during seasonal migrations.

Current U.S. States Affected by Bird Flu in 2024

As of mid-2024, bird flu has been detected in poultry farms, backyard flocks, and wild birds across multiple states. Below is a breakdown of confirmed cases by region:

| State | First Detection in 2024 | Species Affected | Outbreak Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| California | January | Backyard chickens, wild geese | HPAI H5N1 |

| Colorado | February | Commercial turkeys | HPAI H5N1 |

| Iowa | March | Laying hens | HPAI H5N1 |

| Kansas | April | Backyard ducks, wild birds | HPAI H5N1 |

| Minnesota | January | Turkey farms | HPAI H5N1 |

| North Dakota | February | Wild swans, raptors | HPAI H5N1 |

| South Dakota | March | Pheasants, mallards | HPAI H5N1 |

| Texas | May | Quail farms, wild waterfowl | HPAI H5N1 |

| Wisconsin | April | Backyard flocks, eagles | HPAI H5N1 |

This data reflects laboratory-confirmed cases reported to the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS). It's important to note that new cases can emerge rapidly during spring and fall migration periods, especially in the Central and Mississippi Flyways, where large numbers of waterfowl travel annually.

Historical Context of Bird Flu in the United States

The current wave of H5N1 began in early 2022, marking one of the largest avian influenza outbreaks in U.S. history. That year, over 58 million birds were affected across 47 states, leading to massive culling operations and significant economic losses in the egg and turkey industries. The 2023 season saw continued circulation, particularly in western and central states, with spillover into marine mammals like sea lions and seals—a concerning development indicating broader ecological impact.

In 2024, while the number of commercial farm outbreaks has decreased compared to previous years, surveillance shows persistent viral presence in wild bird populations. This suggests an ongoing risk of reintroduction into domestic flocks, especially when biosecurity measures are lax.

Why Certain States Are More Vulnerable

Some states report more frequent bird flu cases due to geographic and ecological factors. Key reasons include:

- Migratory Flyways: States located along major bird migration routes—such as the Mississippi Flyway (e.g., Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri) and the Central Flyway (e.g., Kansas, Nebraska, Texas)—see higher exposure risks.

- Dense Poultry Production: Regions with concentrated poultry farming, like Iowa (the top egg-producing state) and California’s Central Valley, face greater consequences when outbreaks occur.

- Wetland Habitats: Areas rich in wetlands attract large congregations of wild waterfowl, increasing opportunities for virus transmission.

- Backyard Flock Density: States with high numbers of small-scale or hobbyist poultry keepers may experience delayed detection and reporting, allowing the virus to spread before intervention.

Impact on Agriculture and Food Supply

Bird flu outbreaks lead to immediate depopulation of infected flocks to prevent further spread. This not only affects animal welfare but also disrupts egg and poultry meat supplies. In 2024, localized shortages have occurred in states like Iowa and California, causing temporary price increases at retail levels.

However, federal officials emphasize that properly cooked poultry and eggs remain safe to eat. The USDA mandates strict controls on movement and processing during outbreaks, ensuring contaminated products do not enter the food chain.

Public Health Implications and Human Risk

While avian influenza primarily affects birds, there have been rare instances of human infection. As of June 2024, the CDC has confirmed five human cases linked to H5N1 in the U.S., all involving individuals with direct exposure to infected birds (e.g., farm workers, wildlife rehabilitators).

Symptoms in humans range from mild respiratory illness to severe pneumonia. There is no evidence of sustained human-to-human transmission, but public health agencies monitor closely for genetic changes in the virus that could increase pandemic potential.

Guidance for Poultry Owners and Farmers

If you raise chickens, ducks, or other birds, taking preventive steps is crucial. Recommended actions include:

- Enhance Biosecurity: Limit visitors to your property, disinfect boots and tools, and avoid sharing equipment with other farms.

- Isolate New Birds: Quarantine any new additions for at least 30 days before introducing them to existing flocks.

- Prevent Wild Bird Contact: Keep feed and water sources indoors or covered to reduce attraction of wild birds.

- Report Sick Birds Immediately: Contact your state veterinarian or local extension office if you notice sudden deaths, reduced egg production, or neurological signs in your flock.

Advice for Bird Watchers and Outdoor Enthusiasts

For those who enjoy birdwatching, hiking, or wildlife photography, the presence of bird flu doesn’t mean avoiding nature—but caution is advised:

- Do not handle sick or dead birds. If you find a dead bird, report it to your state wildlife agency.

- Avoid touching your face after being outdoors, and wash hands thoroughly after any outdoor activity near waterfowl habitats.

- Use binoculars or telephoto lenses to observe birds from a distance rather than approaching them.

- Clean and disinfect gear (e.g., boots, camera equipment) after visiting areas with known outbreaks.

How to Stay Updated on Bird Flu Activity

Because bird flu status changes frequently, staying informed requires checking reliable, up-to-date sources. Recommended resources include:

- USDA APHIS Avian Influenza Page – Provides maps, case counts, and official press releases.

- CDC Avian Flu Website – Focuses on human health implications and prevention.

- Your State Department of Agriculture or Veterinary Office – Offers localized alerts and response protocols.

- National Wildlife Health Center (NWHC) – Tracks wildlife mortality events related to HPAI.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Despite increased awareness, several myths persist about avian influenza:

- Misconception: Eating chicken or eggs can give you bird flu.

Fact: Proper cooking destroys the virus. No human infections have been linked to consuming properly handled poultry products. - Misconception: All bird flu strains are deadly to humans.

Fact: Most strains do not infect people. H5N1 is rare in humans and typically requires close, prolonged contact with infected birds. - Misconception: Only chickens get bird flu.

Fact: Over 100 bird species—including songbirds, raptors, and shorebirds—can carry and spread the virus.

Future Outlook and Research Directions

Scientists are actively studying how climate change, habitat loss, and global trade influence the persistence and spread of avian influenza. Vaccination trials for poultry are underway, though challenges remain regarding vaccine efficacy and international trade regulations.

Long-term strategies focus on improving early detection systems, enhancing surveillance in wild birds, and promoting stronger biosecurity practices across all scales of poultry production.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Which U.S. states had bird flu in 2024?

- As of mid-2024, confirmed cases were reported in California, Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Texas, and Wisconsin.

- Can humans catch bird flu from wild birds?

- Rarely. Most human cases involve direct contact with infected poultry. Casual observation or proximity to wild birds poses minimal risk.

- Should I stop feeding backyard birds?

- If bird flu is active in your area, consider pausing bird feeders temporarily, especially if sick or dead birds are seen nearby.

- Are migratory birds responsible for spreading bird flu?

- Yes. Migratory waterfowl play a major role in dispersing the virus across continents, though they often show no signs of illness.

- Where can I find real-time updates on bird flu outbreaks?

- Check the USDA APHIS website, your state agriculture department, or the CDC for current outbreak maps and advisories.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4