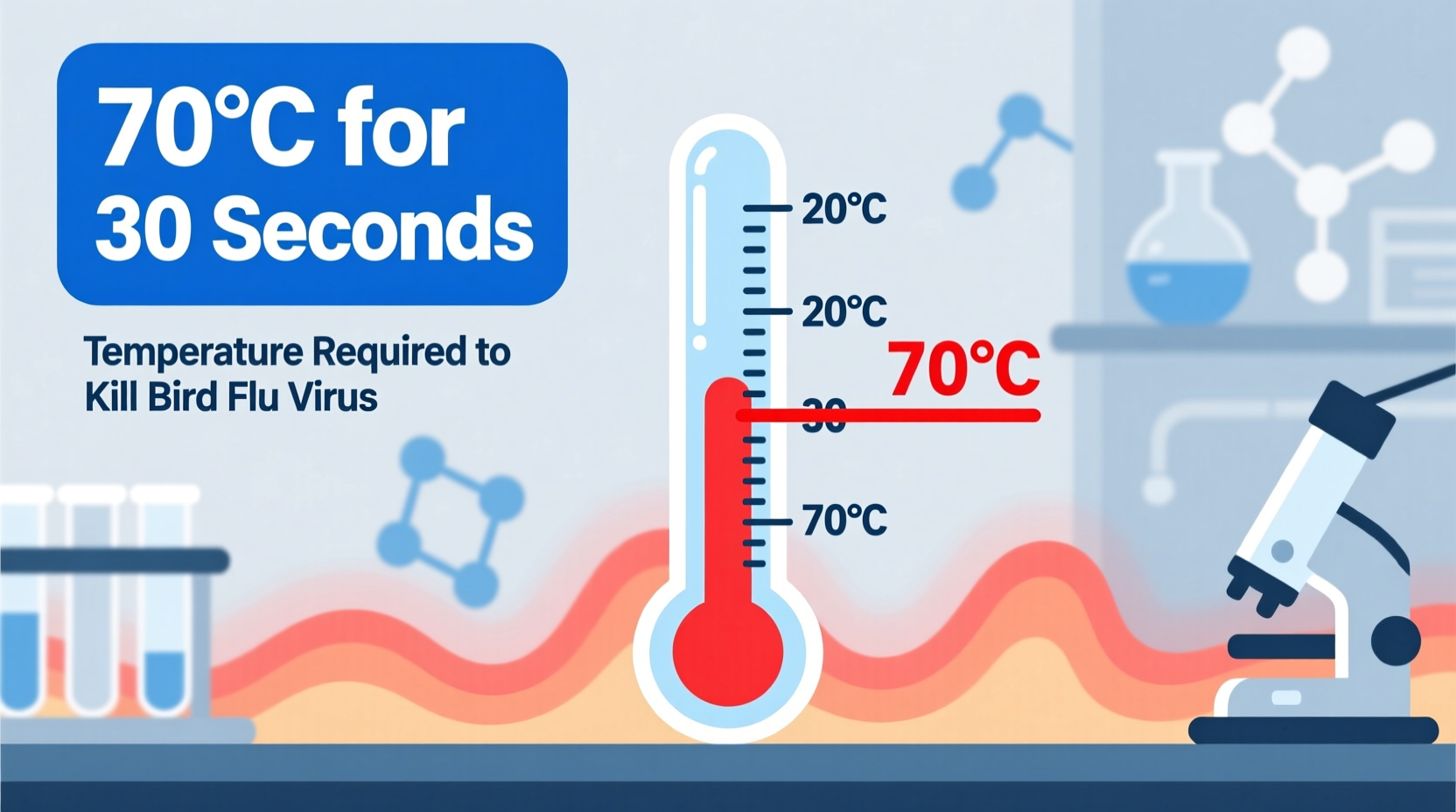

High temperatures can effectively inactivate the avian influenza virus, and understanding what temperature kills bird flu is essential for preventing its spread among poultry and wild bird populations. The virus responsible for bird flu, primarily Influenza A subtypes such as H5N1, is sensitive to heat. Scientific studies and laboratory testing have consistently shown that exposure to temperatures of 70°C (158°F) or higher for at least 30 seconds is sufficient to destroy the virus in contaminated tissues, fluids, and surfaces. This critical thresholdâwhat temperature kills bird fluâis a key factor in food safety protocols, biosecurity measures on farms, and disease control during outbreaks. For example, properly cooking poultry meat to an internal temperature of 70°C ensures that any potential viral contamination is eliminated, making the food safe for consumption.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Biology and Transmission

Bird flu, or avian influenza, is caused by type A influenza viruses that naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds like ducks, gulls, and shorebirds. These species often carry the virus without showing symptoms, acting as reservoirs. However, when the virus spreads to domestic poultryâsuch as chickens, turkeys, and quailâit can cause severe illness and high mortality rates. The most concerning subtype in recent years has been H5N1, which not only devastates poultry flocks but also has zoonotic potential, meaning it can infect humans who have close contact with infected birds.

The virus spreads through direct contact with infected birds, their droppings, or secretions from the nose, mouth, or eyes. It can also be transmitted indirectly via contaminated equipment, clothing, feed, water, or cages. Because the virus can survive in cool, moist environments for extended periodsâsometimes up to several weeks in water or fecesâtemperature plays a crucial role in determining how long the virus remains infectious in the environment.

Thermal Inactivation: How Heat Destroys the Virus

The thermal sensitivity of the avian influenza virus has been well-documented in scientific literature. While the virus can persist for days or even weeks under cold conditions, elevated temperatures significantly reduce its viability. Research conducted by veterinary and public health agenciesâincluding the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)âconfirms that heating biological materials to 70°C (158°F) for a minimum of 30 seconds results in complete viral inactivation.

This principle applies across various contexts:

- Cooking poultry: The USDA recommends cooking all poultry to a minimum internal temperature of 165°F (74°C), which exceeds the threshold needed to kill bird flu viruses.

- Composting carcasses: During mass culling events, proper composting techniques use microbial activity to generate internal temperatures above 55â70°C, effectively neutralizing the virus. \li>Disinfection protocols: Heat treatment of equipment, footwear, and transport vehicles using steam or hot water above 70°C is a standard biosecurity practice.

It's important to note that lower temperatures may reduce viral load over time but do not guarantee complete elimination. For instance, at 56°C (133°F), the virus may take up to three hours to become inactive. At room temperature (around 20â25°C), it can remain viable in feces for 30â35 days and in water for more than two months if kept cold.

Environmental Survival and Seasonal Patterns

The persistence of bird flu in the environment is highly dependent on temperature and humidity. Cold weather prolongs the survival of the virus, which helps explain why outbreaks are more common in winter and early spring. In colder climates, frozen lakes and ponds can harbor the virus in bird droppings, allowing transmission when migratory birds return in large numbers.

In contrast, warmer temperatures accelerate viral degradation. Sunlight (particularly ultraviolet radiation), drying, and higher ambient temperatures collectively contribute to faster inactivation. For example, in tropical regions, where average temperatures exceed 30°C (86°F), the environmental persistence of the virus is generally shorter compared to temperate zones.

However, this does not mean warm climates are immune to outbreaks. Intensive poultry farming, poor biosecurity, and movement of live birds can still facilitate transmission regardless of climate. Therefore, relying solely on ambient temperature to control bird flu is insufficient; active surveillance, rapid response, and strict hygiene practices remain essential.

Biosecurity Measures on Farms and Backyard Flocks

Farmers and backyard poultry keepers play a critical role in preventing the spread of avian influenza. Knowing what temperature kills bird flu is just one part of a broader strategy to protect flocks. Key biosecurity practices include:

- Isolating domestic birds from wild birds, especially during migration seasons.

- Using footbaths with disinfectants at entry points to coops.

- Regularly cleaning and disinfecting cages, feeders, and waterers with solutions proven effective against influenza viruses.

- Avoiding sharing equipment between farms without proper sanitation.

- Monitoring birds daily for signs of illness such as decreased egg production, respiratory distress, swelling, or sudden death.

When an outbreak occurs, depopulation of infected flocks may be necessary. In such cases, carcass disposal methods must ensure viral inactivation. Incineration, deep burial with lime, or composting under controlled temperature conditions are preferred options. Composting, in particular, relies on sustained internal temperatures above 55°C for several days to achieve pathogen destruction.

Public Health Implications and Food Safety

While human infections with bird flu are rare, they can be severe. Most cases occur after prolonged, unprotected contact with infected birds or contaminated environments. There is no evidence that properly cooked poultry or eggs transmit the virus to humans. Regulatory agencies emphasize that cooking meat to an internal temperature of at least 70°C (158°F) kills not only bird flu viruses but also other pathogens like Salmonella and Campylobacter.

Consumers should follow these food safety guidelines:

- Use a food thermometer to verify internal temperatures.

- Avoid consuming raw or undercooked poultry products.

- Wash hands, utensils, and surfaces after handling raw meat.

- Do not wash raw poultry before cooking, as this can spread bacteria and viruses via splashing water.

Despite widespread myths, there is no risk of contracting bird flu from eating commercially produced chicken or eggs in countries with robust veterinary oversight. Surveillance systems monitor flocks, and any detected outbreaks trigger immediate containment actions.

Global Surveillance and Outbreak Response

International cooperation is vital in tracking and responding to avian influenza. Organizations like WOAH, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) maintain global monitoring networks. These systems track outbreaks in both wild and domestic birds, analyze virus strains, and provide guidance on control measures.

Vaccination of poultry is used in some countries but comes with challenges. Vaccinated birds may still carry and shed the virus without showing symptoms, complicating detection efforts. Therefore, vaccination is typically combined with rigorous testing and movement controls.

In the event of an outbreak, authorities implement quarantine zones, restrict bird movements, and conduct culling operations. Rapid diagnosis and transparent reporting help prevent regional spread and protect international trade.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu and Temperature

Several misconceptions persist about how temperature affects bird flu:

- Misconception: Freezing kills the virus.

Fact: Freezing actually preserves the virus. It can survive indefinitely in frozen meat or tissues. - Misconception: Warm weather eliminates bird flu entirely.

Fact: While heat reduces environmental persistence, transmission can still occur through direct contact or contaminated materials. - Misconception: Boiling water alone is enough to disinfect tools.

Fact: Water must reach and maintain at least 70°C for 30 seconds to reliably inactivate the virus.

| Temperature | Effect on Bird Flu Virus | Time Required for Inactivation |

|---|---|---|

| 70°C (158°F) | Complete inactivation | 30 seconds |

| 60°C (140°F) | Significant reduction | 30 minutes |

| 56°C (133°F) | Gradual inactivation | Up to 3 hours |

| 4°C (39°F) | Long-term survival | Weeks to months |

| -70°C (-94°F) | Preservation of virus | Years (in lab storage) |

Practical Tips for Bird Watchers and Outdoor Enthusiasts

For bird watchers, the presence of avian influenza raises concerns about interacting with wild birds. While the risk to humans is low, precautions are advisable:

- Avoid touching sick or dead birds. Report them to local wildlife authorities.

- Do not handle birds without gloves and protective gear.

- Clean binoculars, cameras, and boots after visits to wetlands or areas with high bird density.

- Stay informed about local outbreaks through state wildlife agencies or birding organizations.

Many birding groups now recommend disinfecting equipment with solutions containing at least 70% alcohol or approved virucidal agents, especially after visiting sites with known infections.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What temperature kills bird flu virus instantly?

- Exposure to 70°C (158°F) for at least 30 seconds completely inactivates the bird flu virus.

- Can cooking chicken kill bird flu?

- Yes, cooking chicken to an internal temperature of 70°C (158°F) or higher destroys the virus, making it safe to eat.

- Does freezing poultry kill bird flu?

- No, freezing does not kill the virus. It can survive in frozen meat and requires heat treatment for inactivation.

- How long does bird flu live in the environment?

- In cold, moist conditions, it can last 30â35 days in feces and over two months in water. Heat and sunlight reduce survival time.

- Is it safe to watch wild birds during an outbreak?

- Yes, observing birds from a distance poses minimal risk. Avoid contact with sick or dead birds and disinfect equipment afterward.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4