Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, was a highly contagious viral disease primarily affecting birds, caused by influenza A viruses. The most notable strain, H5N1, emerged in the late 1990s and gained global attention during a major outbreak in 1997 in Hong Kong, where it made the rare jump from birds to humans. Since then, bird flu has been responsible for widespread poultry culling, economic losses in the agricultural sector, and ongoing public health concerns due to its potential to mutate into a form easily transmissible between humans. One of the key long-tail keyword variations naturally integrated here is 'what was the bird flu outbreak history and its impact on human health.'

Understanding Avian Influenza: Origins and Types

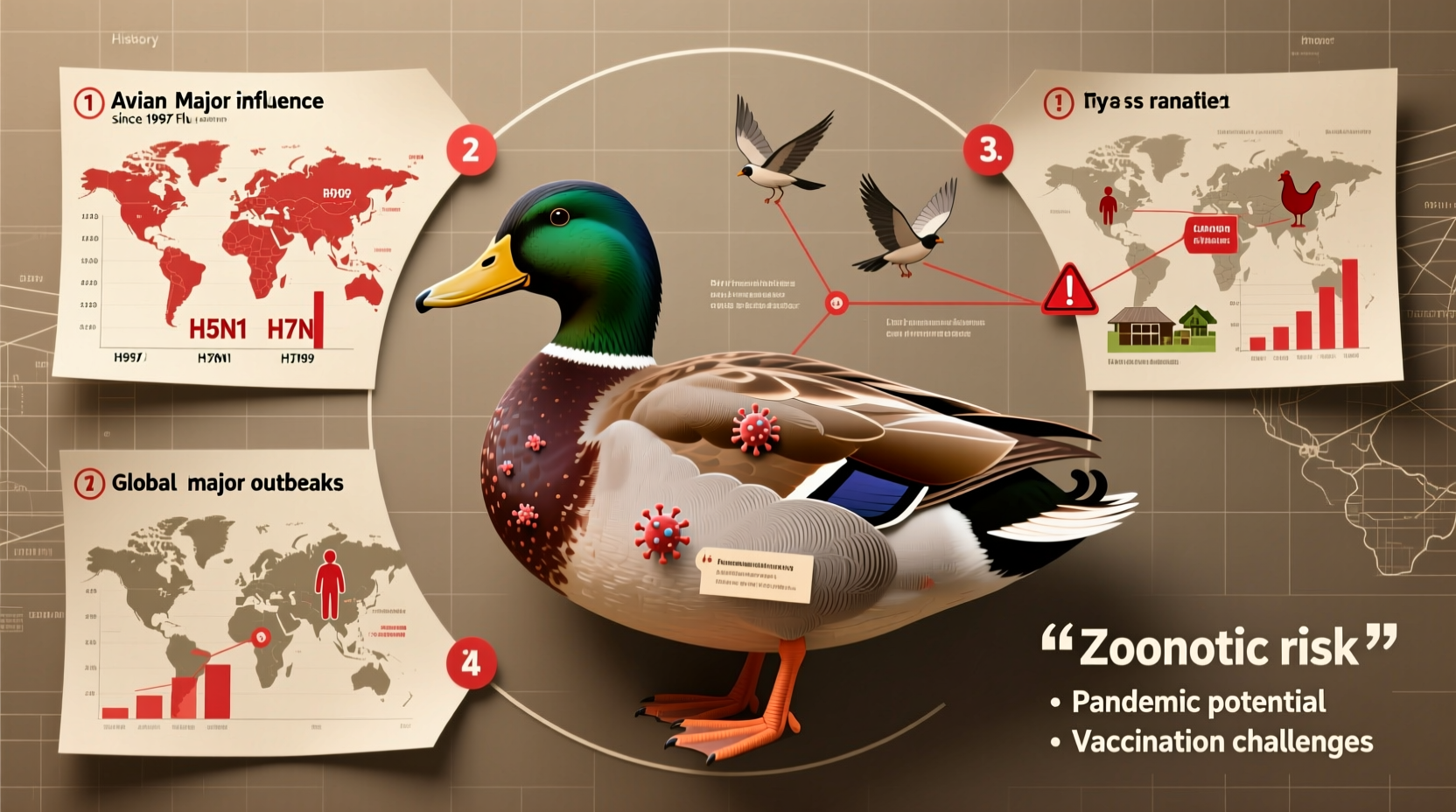

The term 'bird flu' refers to several strains of influenza viruses that naturally occur in wild aquatic birds, such as ducks, gulls, and shorebirds. These birds often carry the virus without showing symptoms, serving as reservoirs. The influenza A virus family is categorized based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, but the most concerning for both animal and human health are H5 and H7.

The first significant recorded instance of bird flu jumping to humans occurred in 1997 in Hong Kong, when the H5N1 strain infected 18 people, resulting in six deaths. This event marked a turning point in global surveillance of zoonotic diseases. The virus was traced back to live poultry markets, prompting authorities to cull over 1.5 million chickens to contain the spread. This outbreak demonstrated that avian influenza could cross species barriers—a phenomenon known as zoonosis.

Major Outbreaks and Global Spread

Following the 1997 Hong Kong incident, bird flu re-emerged in a more aggressive form across Asia in 2003–2004. Countries including Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and China experienced large-scale poultry outbreaks. Migratory birds were identified as key vectors in spreading the virus across regions. By 2005, the H5N1 strain had reached Europe and Africa, carried by wild bird migrations. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported over 600 human cases between 2003 and 2015, with a mortality rate exceeding 50%—one of the highest among known influenza strains.

In 2013, another strain, H7N9, emerged in China, causing severe respiratory illness in humans. Unlike H5N1, which caused visible illness in poultry, H7N9 infected birds asymptomatically, making detection and control more difficult. Over 1,500 human cases were reported, primarily linked to exposure in live bird markets.

A more recent development occurred in 2022 with the spread of the H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, which affected not only poultry but also a wide range of wild bird species and even mammals such as foxes, seals, and sea lions. This raised alarms about increased mammalian adaptation and the possibility of sustained human-to-human transmission in the future.

How Bird Flu Spreads

Bird flu spreads primarily through direct contact with infected birds or their secretions—saliva, nasal discharge, and feces. Contaminated surfaces, feed, water, and equipment can also transmit the virus. Wild birds, especially migratory waterfowl, play a crucial role in disseminating the virus across continents.

Humans typically contract bird flu through close contact with infected poultry, particularly in backyard farms or live markets. There is no evidence of efficient human-to-human transmission, which has so far prevented a pandemic. However, sporadic cases of limited human-to-human spread have been documented, usually among family members in close proximity.

The risk increases during activities such as slaughtering, plucking, or preparing infected birds for consumption. Proper cooking (at temperatures above 70°C) destroys the virus, so eating fully cooked poultry and eggs poses minimal risk.

Symptoms in Birds and Humans

In birds, symptoms vary by strain and species. Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), like H5N1, causes severe illness with high mortality—often killing entire flocks within 48 hours. Signs include sudden death, lack of energy, decreased egg production, swelling of the head, and respiratory distress.

In contrast, low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) may cause mild symptoms or go unnoticed, making early detection challenging.

In humans, bird flu symptoms resemble those of seasonal influenza but can rapidly progress to life-threatening conditions. Common signs include fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, and shortness of breath. Severe cases may develop pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and multi-organ failure.

Prevention and Control Measures

Controlling bird flu requires coordinated efforts at local, national, and international levels. Key strategies include:

- Surveillance and early detection in wild and domestic bird populations

- Rapid culling of infected or exposed poultry flocks

- Biosecurity improvements on farms (e.g., limiting access, disinfecting equipment)

- Closing or regulating live bird markets

- Monitoring migratory bird routes

Vaccination of poultry is used in some countries, though it presents challenges. Vaccinated birds may still carry and shed the virus without showing symptoms, complicating surveillance. Additionally, the virus can evolve rapidly, requiring constant updates to vaccine formulations.

For individuals, especially those working with poultry, protective measures include wearing masks, gloves, and goggles; practicing hand hygiene; and avoiding contact with sick or dead birds.

Public Health Implications and Pandemic Risk

The primary concern surrounding bird flu is its pandemic potential. Influenza viruses can undergo antigenic shift—a process where two different strains infect the same cell and swap genetic material, potentially creating a novel virus capable of efficient human-to-human transmission.

If such a reassortant virus emerges, and if it retains the high mortality rate of H5N1 while gaining transmissibility, the consequences could be devastating. Public health agencies, including the WHO and CDC, maintain stockpiles of antiviral drugs (like oseltamivir) and are developing candidate vaccine viruses for rapid deployment.

Global initiatives like the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) monitor circulating strains and assess pandemic risks. Early warning systems and international cooperation are essential for timely response.

Impact on Agriculture and Economy

Bird flu outbreaks have profound economic impacts. Massive culling operations disrupt food supply chains, affect trade, and lead to financial losses for farmers. Export bans on poultry and related products can last months or years, depending on disease status.

In the United States, for example, a 2015 H5N1 outbreak resulted in the loss of over 50 million birds and cost taxpayers nearly $1 billion in compensation and control measures. Similarly, the 2022–2023 outbreaks led to record egg prices due to the depopulation of laying hens.

| Year | Strain | Region Affected | Human Cases | Mortality Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | H5N1 | Hong Kong | 18 | 33% |

| 2003–2015 | H5N1 | Asia, Middle East, Africa | 862 | ~53% |

| 2013–2017 | H7N9 | China | 1,568 | ~40% |

| 2022–2024 | H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b | Global | Spillover to mammals; few human cases | High in animals |

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about bird flu. One common misconception is that eating chicken or eggs can easily transmit the virus. As previously noted, proper cooking eliminates the virus, so commercially sourced and well-cooked poultry is safe.

Another myth is that bird flu is no longer a threat because it hasn't caused a pandemic. In reality, the virus continues to circulate in bird populations worldwide and evolves constantly, posing an ongoing risk.

Some believe that only wild birds spread the disease, ignoring the role of legal and illegal poultry trade in amplifying outbreaks. In fact, movement of domestic birds often plays a larger role in localized spread than wild migration.

What You Can Do: Practical Tips for the Public

While the average person's risk remains low, certain precautions are advisable:

- Avoid contact with sick or dead birds, especially in areas with known outbreaks.

- Report sightings of multiple dead birds to local wildlife or agricultural authorities.

- If you keep backyard poultry, practice strict biosecurity: isolate new birds, sanitize equipment, and prevent contact with wild birds.

- Stay informed through official sources like the CDC, WHO, or national veterinary services.

- During outbreaks, consider avoiding live bird markets, particularly when traveling abroad.

Bird watchers and ornithologists should clean boots and gear after visiting wetlands or bird sanctuaries to prevent inadvertently transporting the virus.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What was the bird flu and when did it start?

Bird flu, or avian influenza, refers to influenza A viruses that primarily infect birds. The first known human case occurred in 1997 in Hong Kong with the H5N1 strain.

Can bird flu spread from human to human?

Sustained human-to-human transmission has not been observed. Rare, limited cases have occurred among close contacts, but the virus does not spread easily between people.

Is it safe to eat chicken and eggs during a bird flu outbreak?

Yes, as long as poultry and eggs are properly cooked (internal temperature above 70°C). The virus is destroyed by heat, and commercial food safety practices reduce risk significantly.

How is bird flu different from seasonal flu?

Seasonal flu spreads easily among humans and has lower mortality. Bird flu primarily affects birds and rarely infects humans, but when it does, it tends to cause more severe illness.

Are there vaccines for bird flu?

There are experimental vaccines for certain strains like H5N1, developed for pandemic preparedness. These are not widely available to the public but are stockpiled by governments.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4