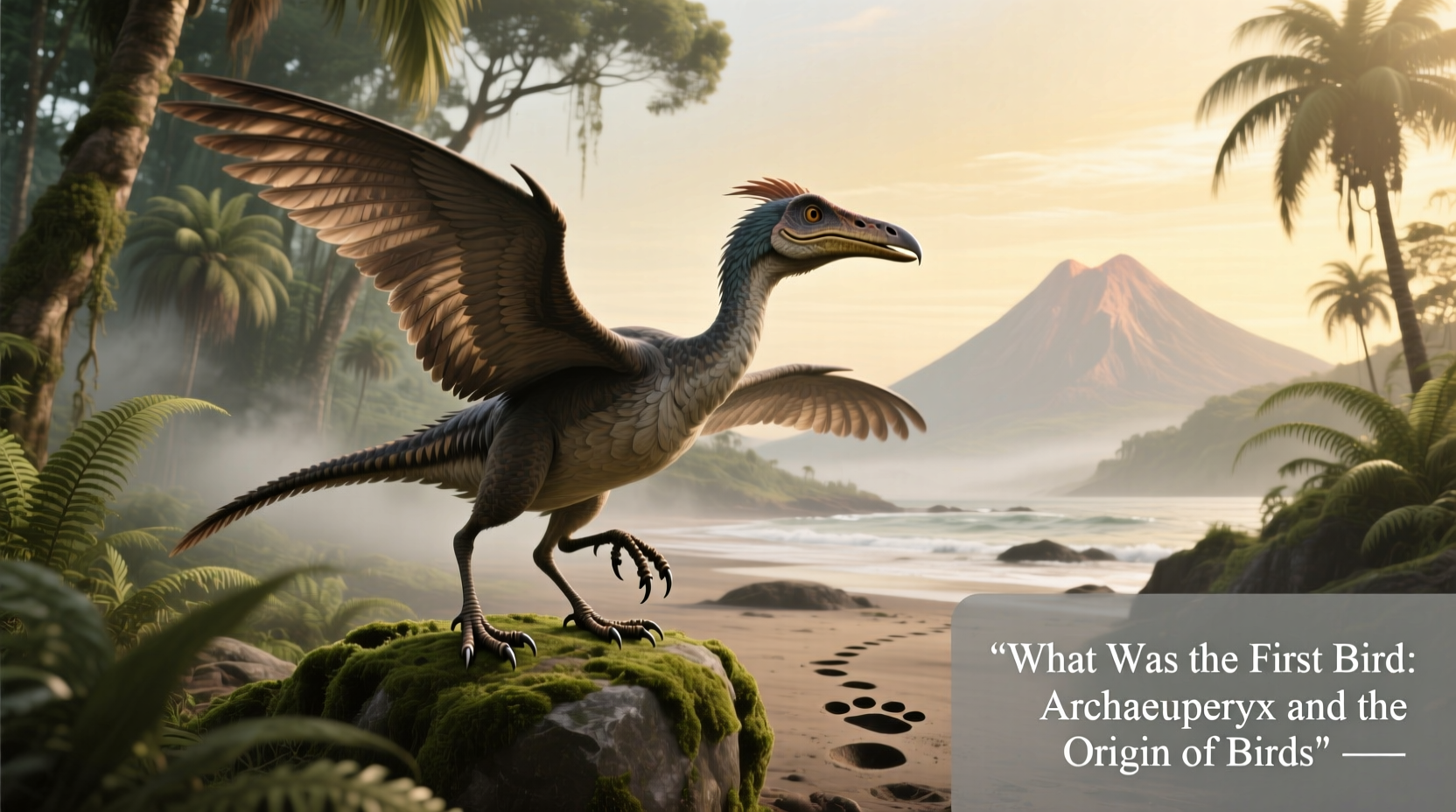

The first bird in evolutionary history is widely considered to be Archaeopteryx lithographica, a feathered dinosaur that lived approximately 150 million years ago during the Late Jurassic period. When asking 'what was the first bird,' paleontologists and evolutionary biologists point to Archaeopteryx as the earliest known species exhibiting both avian and reptilian traits, making it a crucial transitional fossil in the story of bird evolution. This remarkable creature possessed feathers, wings, and a wishbone—key characteristics of modern birds—while also retaining teeth, a long bony tail, and clawed fingers, features more typical of small theropod dinosaurs. Understanding what was the first bird not only sheds light on avian origins but also illustrates how complex biological transitions occur over millions of years through natural selection.

The Fossil Evidence Behind the First Bird

Fossils of Archaeopteryx were first discovered in the early 1860s in limestone quarries near Solnhofen, Germany. These exceptionally preserved specimens provided unprecedented insight into early avian anatomy. The fine-grained sedimentary rock captured delicate details such as feather impressions, allowing scientists to confirm that Archaeopteryx had flight-capable plumage similar to modern birds. To date, at least 12 well-preserved fossils have been identified, each contributing to our understanding of this pivotal species.

One of the most famous specimens, the Berlin specimen, clearly shows asymmetrical flight feathers—a hallmark of powered flight. However, debate continues about whether Archaeopteryx could sustain flapping flight or merely glide between trees. Its shoulder joint structure suggests limited upstroke capability, indicating it may not have been as agile in the air as today’s passerines. Still, the presence of perching feet, a reversed hallux (backward-facing toe), and feather morphology strongly support an arboreal lifestyle and some degree of aerial locomotion.

Evolutionary Context: From Dinosaurs to Birds

To understand what was the first bird, one must examine the broader context of theropod dinosaur evolution. Over the past few decades, discoveries in China—particularly in the Liaoning Province—have uncovered numerous feathered non-avian dinosaurs such as Velociraptor, Microraptor, and Anchiornis. These findings reinforce the now widely accepted theory that birds are direct descendants of small, carnivorous theropods.

Archaeopteryx sits near the base of the avian family tree but is no longer seen as the absolute origin point of all birds. Some researchers argue that other species like Aurornis xui or Xiaotingia zhengi, slightly older or more basal in phylogenetic analyses, might predate Archaeopteryx as the earliest bird. Nevertheless, due to its well-documented anatomy and historical significance, Archaeopteryx remains the quintessential example when discussing the emergence of birds from their dinosaur ancestors.

| Feature | Archaeopteryx | Modern Birds | Theropod Dinosaurs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feathers | Yes (flight feathers) | Yes | Some species (e.g., Velociraptor) |

| Teeth | Yes | No | Yes |

| Bony Tail | Long, bony tail | Short pygostyle | Long bony tail |

| Wishbone (Furcula) | Present | Present | Present in many |

| Flight Capability | Limited (likely gliding or weak flapping) | Strong powered flight | None |

Defining 'Bird': A Scientific Challenge

Answering 'what was the first bird' depends heavily on how we define 'bird.' Biologically, there is no single moment when a reptile became a bird. Instead, bird-like traits evolved incrementally across generations. Some scientists use cladistics—the classification based on common ancestry—to define birds as all descendants of the most recent common ancestor of all living birds (Neornithes). Under this definition, Archaeopteryx falls just outside crown-group birds but within Avialae, the broader lineage leading to modern birds.

Others adopt a more inclusive approach, considering any animal with key avian adaptations—such as flight feathers and a fully developed wing—as a bird. By these criteria, Archaeopteryx qualifies as the first true bird. Yet newer fossil discoveries challenge even this view. For instance, Microraptor, though classified as a dromaeosaurid dinosaur, had four wings and could likely glide effectively. This blurs the line between non-avian dinosaurs and early birds, emphasizing that the evolution of flight occurred along a spectrum rather than in discrete steps.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Early Birds

Beyond biology, the question of what was the first bird resonates in mythology, religion, and human symbolism. In many cultures, birds represent freedom, transcendence, and the soul’s journey beyond earthly bounds. The idea of a primordial bird emerging from ancient forests or rising from reptilian forms taps into deep archetypes about transformation and the origins of life.

In Christian iconography, for example, the dove symbolizes the Holy Spirit and new beginnings—echoing themes of creation and renewal. Similarly, in Native American traditions, ravens and eagles are often seen as creators or messengers between worlds. While these narratives are mythological, they parallel scientific accounts of birds evolving from earlier forms, suggesting a shared human fascination with avian origins.

How Scientists Study Ancient Bird Evolution

Paleontologists use multiple tools to investigate what was the first bird and how avian traits evolved. Comparative anatomy allows researchers to analyze skeletal structures across species, identifying homologous features shared through descent. Phylogenetic analysis uses genetic and morphological data to construct evolutionary trees, helping determine relationships among extinct and living organisms.

Advanced imaging technologies, such as CT scanning, enable scientists to peer inside fossils without damaging them. These scans reveal internal structures like brain cavities and inner ear configurations, offering clues about sensory abilities and behavior. Additionally, geochemical analysis of fossilized bones and surrounding sediments helps pinpoint the age and environmental conditions in which these animals lived.

Fieldwork remains essential. Expeditions to fossil-rich regions in China, Mongolia, and North America continue to uncover new specimens that refine our understanding of early avian evolution. Each discovery adds another piece to the puzzle of how flight, feathers, and metabolic adaptations arose over tens of millions of years.

Common Misconceptions About the First Bird

Several misconceptions surround the identity of the first bird. One common error is assuming that Archaeopteryx was the direct ancestor of all modern birds. In reality, it is better understood as a close relative near the base of the avian lineage—an evolutionary cousin rather than a great-great-grandparent.

Another misconception is that feathers evolved solely for flight. Evidence shows that feathers initially served functions such as insulation, display, and camouflage in ground-dwelling dinosaurs before being co-opted for aerodynamic purposes. This underscores the concept of exaptation—where a trait evolves for one purpose but later becomes useful for another.

Finally, some believe that once birds appeared, dinosaurs went extinct. In fact, birds are dinosaurs in the same way that bats are mammals. Non-avian dinosaurs (like Tyrannosaurus rex) died out 66 million years ago, but avian dinosaurs—birds—survived and diversified into over 10,000 species today.

Modern Implications: Studying Ancient Origins to Protect Today’s Birds

Understanding what was the first bird isn’t just an academic exercise—it has real-world applications. Insights from evolutionary biology help conservationists predict how species might adapt to climate change, habitat loss, and other pressures. By studying how early birds survived mass extinctions and ecological shifts, scientists gain perspective on resilience and adaptation.

Moreover, public interest in fossils like Archaeopteryx fosters engagement with science and natural history. Museums featuring early bird fossils inspire future generations of biologists, paleontologists, and environmental stewards. Educational programs that connect ancient evolution with modern biodiversity encourage holistic thinking about life on Earth.

FAQs About the First Bird

- Was Archaeopteryx the first animal with feathers?

- No. Feathers have been found on several non-avian dinosaurs, including Sinosauropteryx and Caudipteryx, predating or contemporaneous with Archaeopteryx. Feathers evolved before flight.

- Could Archaeopteryx fly like modern birds?

- Likely not. It probably engaged in limited flapping or gliding flight, lacking the advanced musculature and skeletal adaptations of modern flying birds.

- Are there older fossils than Archaeopteryx that might be birds?

- Yes. Fossils like Aurornis xui (~160 million years old) may be slightly older and more primitive, though classification debates persist.

- Is Archaeopteryx still considered the first bird?

- While still iconic, current research places other species near or just below Archaeopteryx on the evolutionary tree. It remains a key representative of early avian evolution.

- How do scientists determine if a fossil is a bird or a dinosaur?

- They analyze anatomical features—such as skull shape, wrist flexibility, feather type, and shoulder girdle orientation—within a phylogenetic framework to assess evolutionary relationships.

In summary, answering 'what was the first bird' leads us to Archaeopteryx lithographica, a creature that embodies the transition from dinosaurs to birds. Though newer discoveries refine our understanding, Archaeopteryx endures as a symbol of evolutionary innovation. Its blend of reptilian and avian traits offers profound insights into how nature builds complexity over time. Whether viewed through the lens of science, culture, or curiosity, the search for the first bird reveals much about the interconnectedness of life on Earth.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4