The bird flu, also known as avian influenza, first emerged in domestic poultry in Italy in 1878, marking the earliest recorded outbreak of what scientists now classify as highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). This initial identification of bird flu set the foundation for understanding outbreaks that have since evolved over more than a century. The term 'avian influenza' was not widely used until later, but historical accounts from the late 19th century describe a disease affecting birds with symptoms consistent with modern definitions of the virus. A pivotal moment in tracking the origin of bird flu came in 1955 when researchers confirmed that the causative agent was an influenza A virus, specifically subtypes that primarily circulate among birds. Since then, multiple strains have surfaced, including H5N1—which gained global attention after a major outbreak began in 1996 in China’s Guangdong Province—ushering in a new era of surveillance and international concern about zoonotic transmission. Understanding when did the bird flu start is essential to grasping its long-term impact on both wildlife and human health.

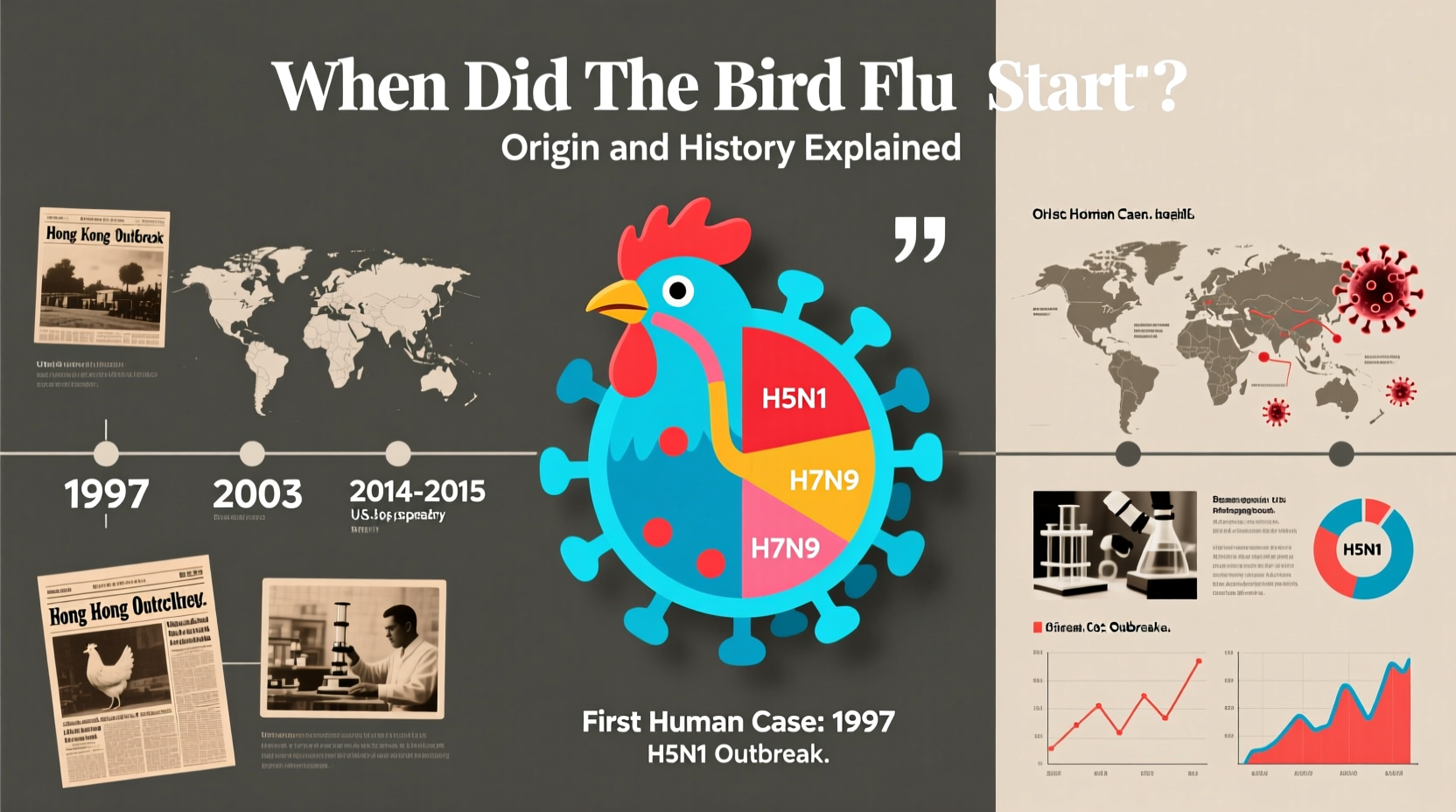

Historical Timeline of Major Bird Flu Outbreaks

The story of avian influenza spans over 140 years, with each phase contributing to our current understanding of viral evolution and pandemic preparedness. While the first documented case dates back to 1878 in Northern Italy, it wasn't until the mid-20th century that virology advanced enough to isolate and categorize the virus accurately.

In 1955, scientists identified the influenza A virus as the cause of avian flu, confirming its classification within the Orthomyxoviridae family. This breakthrough allowed for better tracking and differentiation between low-pathogenic (LPAI) and high-pathogenic (HPAI) strains. One of the most significant developments occurred in 1996 when the H5N1 strain was isolated from geese in Guangdong, China. This strain proved unusually lethal to birds and showed early signs of crossing into humans—a rare but dangerous phenomenon known as zoonosis.

The year 1997 marked the first confirmed human death due to H5N1 during an outbreak in Hong Kong, prompting immediate culling of poultry markets and raising alarms worldwide. Over the next decade, the virus spread across Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and parts of Europe through migratory bird routes and commercial poultry trade. By 2005, wild birds, particularly bar-headed geese at Qinghai Lake in China, were found carrying the virus over long distances, illustrating how ecological factors influence transmission dynamics.

More recently, the H5N8 strain emerged in 2014, followed by a highly contagious variant, H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, which began spreading globally in 2020 and intensified in 2021–2023. This latest wave affected millions of birds across North America, Europe, and Asia, leading to unprecedented losses in commercial flocks and triggering widespread biosecurity measures.

Biological Origins and Virus Subtypes

Bird flu is caused by influenza A viruses, which are naturally hosted in wild aquatic birds such as ducks, gulls, and shorebirds. These species often carry the virus without showing symptoms, acting as reservoirs for various subtypes based on combinations of hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) surface proteins. To date, 18 H subtypes and 11 N subtypes have been identified, though only a few—including H5 and H7—are known to develop into highly pathogenic forms under certain conditions.

Low-pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) typically causes mild illness in birds, such as ruffled feathers or decreased egg production. However, LPAI can mutate into HPAI after circulating in domestic poultry populations, where dense housing and limited genetic diversity accelerate viral adaptation. Once HPAI emerges, mortality rates in chickens and turkeys can exceed 90%, necessitating rapid detection and containment.

The H5N1 strain remains the most studied due to its persistence and ability to occasionally infect humans. Since 1997, there have been over 900 reported human cases globally, with a fatality rate exceeding 50%. Most infections result from direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environments, rather than sustained human-to-human transmission—though this remains a key concern for public health officials monitoring potential pandemics.

Global Spread Mechanisms: Migration, Trade, and Climate

Understanding how bird flu spreads requires examining three primary vectors: wild bird migration, global poultry trade, and environmental changes linked to climate patterns. Migratory birds play a crucial role in dispersing the virus across continents. Species like the common teal, mallard, and ruddy shelduck travel thousands of miles annually along flyways that intersect with agricultural zones, increasing spillover risk.

Data from satellite tagging and genomic sequencing show that outbreaks often follow seasonal migration timelines. For example, increased detections in North America occur between fall and spring, coinciding with southward and northward movements. In Europe, outbreaks peak during winter months when waterfowl congregate in wetlands, facilitating virus exchange.

Commercial poultry operations also contribute to spread, especially in regions with inadequate biosecurity protocols. Live bird markets, common in parts of Asia and Africa, serve as amplification points where diverse species mix, enabling cross-species transmission. Additionally, legal and illegal movement of poultry products can introduce the virus to previously unaffected areas.

Climate change may be altering transmission patterns. Warmer temperatures extend the survival time of the virus in water and soil, while shifting precipitation patterns affect wetland availability, concentrating birds in smaller areas and increasing contact rates. Some studies suggest that earlier springs and delayed winters could lengthen the window of active viral circulation.

Impact on Wildlife, Poultry, and Human Health

The consequences of avian influenza extend beyond individual bird deaths. Mass die-offs of wild birds, including endangered species like the whooping crane and red-crowned crane, have raised conservation concerns. In 2022, over 10,000 seabirds died at a colony in Alaska due to H5N1, highlighting ecosystem-level disruptions.

Poultry industries face severe economic repercussions. In the United States alone, the 2022–2023 outbreak led to the depopulation of more than 58 million birds, causing egg prices to surge and disrupting supply chains. Governments responded with compensation programs, enhanced surveillance, and temporary export bans to protect trade interests.

From a public health standpoint, while human cases remain rare, they are closely monitored. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and World Health Organization (WHO) maintain watchlists for mutations that could enhance transmissibility between people. Antiviral drugs like oseltamivir are stockpiled, and candidate vaccines for H5N1 are developed in anticipation of future needs.

Prevention and Biosecurity Measures for Bird Owners

Whether managing backyard flocks or large-scale farms, implementing strong biosecurity practices is critical to preventing avian influenza outbreaks. Key strategies include:

- Limiting access to bird enclosures by visitors and workers

- Using dedicated clothing and footwear when handling birds

- Disinfecting equipment, cages, and transport vehicles regularly

- Avoiding contact between domestic birds and wild waterfowl

- Monitoring flocks daily for signs of illness (lethargy, swelling, reduced appetite)

- Reporting sick or dead birds immediately to local veterinary authorities

Backyard bird keepers should register their flocks with national databases where available and stay informed via official alerts from agencies like the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) or equivalent bodies abroad. During outbreak periods, indoor confinement may be mandated to reduce exposure risks.

Current Surveillance and International Response

Global coordination is vital in managing avian influenza. The World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), formerly OIE, maintains a real-time reporting system for member countries to share outbreak data. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) supports capacity building in developing nations, helping improve diagnostic capabilities and response planning.

In North America, the Wild Bird Surveillance Program tests thousands of samples annually to detect early signs of virus circulation. Similarly, the European Union operates the EU Reference Laboratory for Avian Influenza, coordinating testing and research across member states.

Vaccination is used selectively, mainly in high-risk regions like parts of Southeast Asia and Egypt. However, widespread vaccination poses challenges, including interference with surveillance (since vaccinated birds may still shed virus) and the potential for immune pressure driving viral evolution. Therefore, most Western countries rely on stamping-out policies—rapid culling and disposal of infected flocks—as the primary control method.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about avian influenza that can hinder effective prevention and response. One common belief is that eating properly cooked poultry or eggs can transmit the virus. Scientific evidence confirms that standard cooking temperatures (above 70°C/158°F) destroy the virus, making food safe if handled hygienically.

Another misconception is that all bird species are equally susceptible. In reality, gallinaceous birds (chickens, turkeys, quail) are far more vulnerable than many wild species. Raptors and scavengers may become infected by feeding on diseased carcasses, but passerines (songbirds) rarely contract or spread the virus.

There's also confusion about human-to-human transmission. Despite isolated reports of limited person-to-person spread, no sustained community transmission has occurred. Public health agencies emphasize that seasonal flu poses a much greater daily threat than bird flu.

| Strain | First Detected | Notable Outbreak Years | Zoonotic Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| H5N1 | 1996 (China) | 1997, 2003–2006, 2020–2023 | High (over 900 human cases) |

| H5N8 | 2014 (South Korea) | 2014–2015, 2020–2021 | Low (few suspected cases) |

| H7N9 | 2013 (China) | 2013–2017 | Medium (over 1,500 human cases) |

| H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b | 2020 (global) | 2020–2024 | Moderate (increasing wild bird & mammal cases) |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- When did the bird flu first appear?

- The first recorded outbreak of bird flu occurred in 1878 in Italy, although the virus was not scientifically identified until 1955.

- Can humans get bird flu?

- Yes, but only through close contact with infected birds. Human-to-human transmission is extremely rare.

- Is it safe to eat chicken and eggs during a bird flu outbreak?

- Yes, as long as poultry and eggs are thoroughly cooked. The virus is destroyed at normal cooking temperatures.

- How does bird flu spread to new countries?

- Primarily through migratory birds and international movement of infected poultry or contaminated materials.

- What should I do if I find a dead wild bird?

- Do not touch it. Report it to your local wildlife agency or veterinarian for testing, especially during active outbreak periods.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4