The bird flu pandemic, specifically referring to the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1, has not occurred as a full-scale human pandemicâyet. However, the most significant global outbreak of avian influenza in birds began in 2003 and continued into 2006, marking what many experts consider the largest and most severe bird flu epidemic in history. This period saw widespread transmission among poultry populations across Asia, Europe, and Africa, with sporadic cases of human infection reported primarily through direct contact with infected birds. The term 'when was the bird flu pandemic' often refers to this critical phase of viral spread between 2003 and 2006, during which public health systems worldwide heightened surveillance due to fears of mutation into a form easily transmissible between humans.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Origins and Biological Nature

Avian influenza, commonly known as bird flu, is caused by type A influenza viruses that naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds such as ducks, gulls, and shorebirds. These species typically carry the virus without showing symptoms, acting as reservoirs for transmission. The virus belongs to the Orthomyxoviridae family and is classified based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, but the most concerning strains for both animal and human health are H5 and H7, particularly the H5N1 strain.

The biological mechanism of transmission occurs when infected birds shed the virus through saliva, nasal secretions, and feces. Other birds become infected when they come into contact with contaminated surfaces or materials. While most avian influenza strains cause mild illness in birds, certain variantsâlike HPAI H5N1âcan lead to rapid death in domestic poultry flocks, with mortality rates approaching 100% within 48 hours of infection.

Historical Timeline of Major Bird Flu Outbreaks

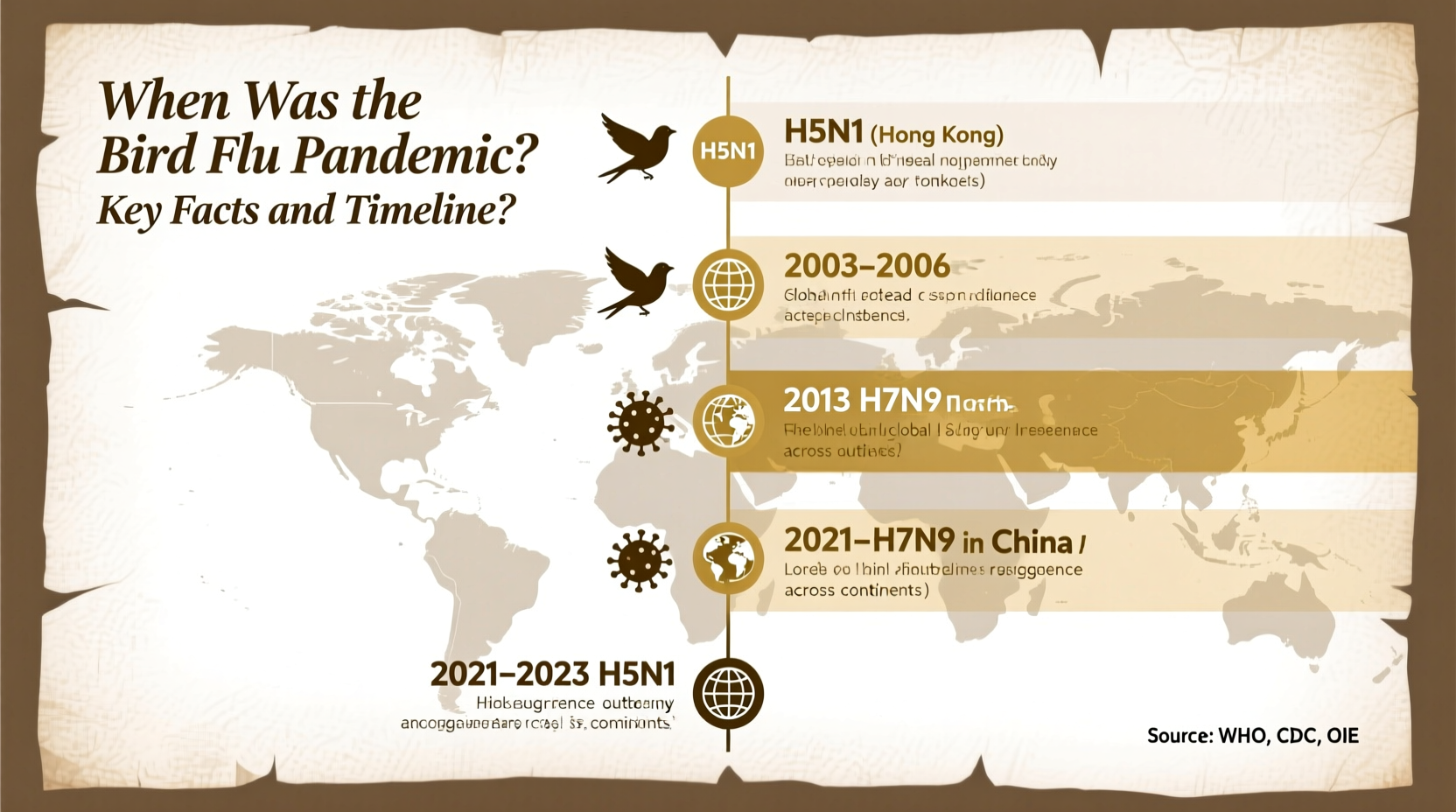

The first recorded outbreak of H5N1 occurred in 1996 in geese in China's Guangdong Province. However, it wasn't until late 2003 that the virus began spreading rapidly across multiple countries. Hereâs a timeline highlighting key events:

- 1997 â Hong Kong: First known human case of H5N1 infection; 18 people infected, 6 died. Poultry culling helped contain the outbreak.

- December 2003 â South Korea: Initial detection in commercial poultry farms, followed by rapid spread to Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia, and Indonesia.

- 2004 â Global Expansion: Over 100 million birds died or were culled across eight Asian countries. The World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) declared an international emergency.

- 2005 â Spread to Europe and Africa: Migratory birds carried the virus westward. Cases confirmed in Russia, Turkey, Romania, Nigeria, and Egypt.

- 2006 â Peak Human Infections: WHO reported over 250 human cases globally with a fatality rate exceeding 60%. Most infections linked to close contact with sick or dead poultry.

- 2008â2013: Continued sporadic outbreaks, especially in Southeast Asia and Egypt.

- 2014âPresent: Emergence of new clades (genetic branches), including H5N8 and H5N6, affecting both wild and farmed birds globally.

This historical context helps clarify when was the bird flu pandemic from a zoonotic and agricultural standpointânot as a human-to-human pandemic, but as a persistent threat to global biosecurity.

Differences Between an Epidemic and a Pandemic in the Context of Bird Flu

A common misunderstanding arises around the use of the word âpandemicâ when discussing bird flu. A pandemic requires sustained human-to-human transmission across multiple continents. Although H5N1 has caused over 900 confirmed human cases since 2003 (with about half resulting in death), there has been no evidence of efficient or prolonged person-to-person spread. Therefore, while the avian influenza outbreaks constitute a global epidemic in birdsâand a serious zoonotic concernâthey have not met the criteria for a human pandemic.

In contrast, true influenza pandemicsâsuch as the 1918 Spanish flu (H1N1), the 1957 Asian flu (H2N2), the 1968 Hong Kong flu (H3N2), and the 2009 swine flu (H1N1)âinvolved novel influenza strains capable of easy airborne transmission between people. Public health agencies like the World Health Organization (WHO) maintain pandemic preparedness plans specifically because of concerns that H5N1 or similar avian strains could mutate to acquire this capability.

Recent Developments: Is Bird Flu Still a Threat Today?

Yes, avian influenza remains an active and evolving threat. Since 2020, a new wave of H5N1âdesignated clade 2.3.4.4bâhas led to unprecedented outbreaks in wild birds and commercial poultry operations across North America, Europe, and parts of South America. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), tens of millions of birds have been affected in recent years.

In 2022, the United States experienced its worst bird flu outbreak in history, impacting more than 58 million birds across 47 states. Unlike earlier waves, this strain has shown increased ability to infect mammals, including foxes, seals, sea lions, and even dairy cattle, raising alarm among scientists. In April 2024, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first U.S. case of H5N1 in a human associated with exposure to infected dairy cows in Texas, underscoring ongoing zoonotic risks.

| Year | Key Event | Geographic Impact | Human Cases (Confirmed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | First human H5N1 infection | Hong Kong | 18 |

| 2003â2006 | Major global bird flu epidemic | Asia, Europe, Africa | ~300 |

| 2014â2015 | H5N8 spreads via migratory birds | Europe, North America | 0 |

| 2022â2024 | Clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 surge | Global, including Americas | Over 50 (including U.S. case) |

How Bird Flu Affects Humans: Symptoms, Risk Factors, and Prevention

Human infections with avian influenza remain rare but can be severe. Symptoms range from typical flu-like signsâfever, cough, sore throat, muscle achesâto more serious complications such as pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and multi-organ failure. The incubation period is usually 2 to 8 days after exposure.

Those at highest risk include:

- Poultry farmers and backyard flock owners

- Veterinarians and animal health workers

- People handling sick or dead birds

- Individuals in regions experiencing active outbreaks

To reduce risk:

- Avoid contact with sick or dead birds.

- Wear protective gear (gloves, masks) when handling poultry.

- Cook poultry and eggs thoroughly (internal temperature â¥165°F / 74°C).

- Report unusual bird deaths to local wildlife authorities.

- Stay informed through national health and agriculture departments.

Global Surveillance and Response Systems

International cooperation plays a crucial role in monitoring and controlling avian influenza. Key organizations involved include:

- World Health Organization (WHO): Coordinates global public health response and monitors potential pandemic threats.

- World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH): Tracks animal disease outbreaks and sets reporting standards.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO): Supports developing nations in improving biosecurity and early warning systems.

- CDC and USDA (U.S.): Conduct surveillance, issue guidelines, and manage outbreak responses domestically.

Data sharing, rapid diagnostics, and vaccine development are central components of current strategies. Experimental H5N1 vaccines exist and are stockpiled in some countries, though they are not widely available to the general public.

Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about avian influenza:

- Misconception: Eating chicken or eggs can give you bird flu.

Fact: Properly cooked poultry and eggs pose no risk. The virus is destroyed at cooking temperatures above 70°C (158°F). - Misconception: The bird flu is currently spreading from person to person.

Fact: No sustained human-to-human transmission has been documented. \li>Misconception: Only wild birds spread the virus.

Fact: While wild birds play a major role, poor biosecurity on farms is a primary driver of large-scale outbreaks.

What Should Travelers and Bird Watchers Know?

For bird watchers and outdoor enthusiasts, the rise of HPAI raises important considerations. During periods of high viral activity, some national parks and wildlife refuges restrict access to wetlands or discourage feeding birds. Always check local advisories before visiting natural areas.

Tips for safe bird watching:

- Maintain distance from sick or dead birds.

- Do not touch birds or their droppings.

- Clean binoculars, cameras, and footwear after visits to birding sites.

- Participate in citizen science programs like eBird to help track bird health trends.

Future Outlook and Preparedness

The recurring nature of avian influenza underscores the need for long-term preparedness. Scientists continue to monitor genetic changes in circulating strains, particularly mutations in the hemagglutinin protein that could enhance binding to human receptors. Enhanced farm biosecurity, early detection systems, and international coordination are essential to prevent another major outbreak.

Public awareness and responsible practicesâfrom backyard chicken keepers to global policymakersâare vital. While the world narrowly avoided a bird flu pandemic in the 2003â2006 era, the next high-risk strain may emerge at any time. Understanding when was the bird flu pandemic historically helps frame todayâs vigilance as part of an ongoing effort to protect both animal and human health.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Was there ever a bird flu pandemic?

- No, there has never been a full-scale bird flu pandemic in humans. However, large-scale epidemics in birds occurred notably between 2003 and 2006, and again since 2022.

- When did the bird flu start in humans?

- The first human case of H5N1 was recorded in Hong Kong in 1997. Sustained outbreaks in humans did not occur, but sporadic infections have continued since then.

- Can bird flu spread from human to human?

- There is no evidence of efficient or sustained human-to-human transmission. Rare instances of limited spread among close contacts have been investigated but did not lead to wider outbreaks.

- Is bird flu still around in 2024?

- Yes, highly pathogenic H5N1 continues to circulate globally, especially in wild birds and poultry. New cases in mammals and one human case in the U.S. were reported in early 2024.

- Should I be worried about bird flu?

- For most people, the risk is very low. Those working with birds should follow safety protocols. General public should stay informed through official health sources.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4