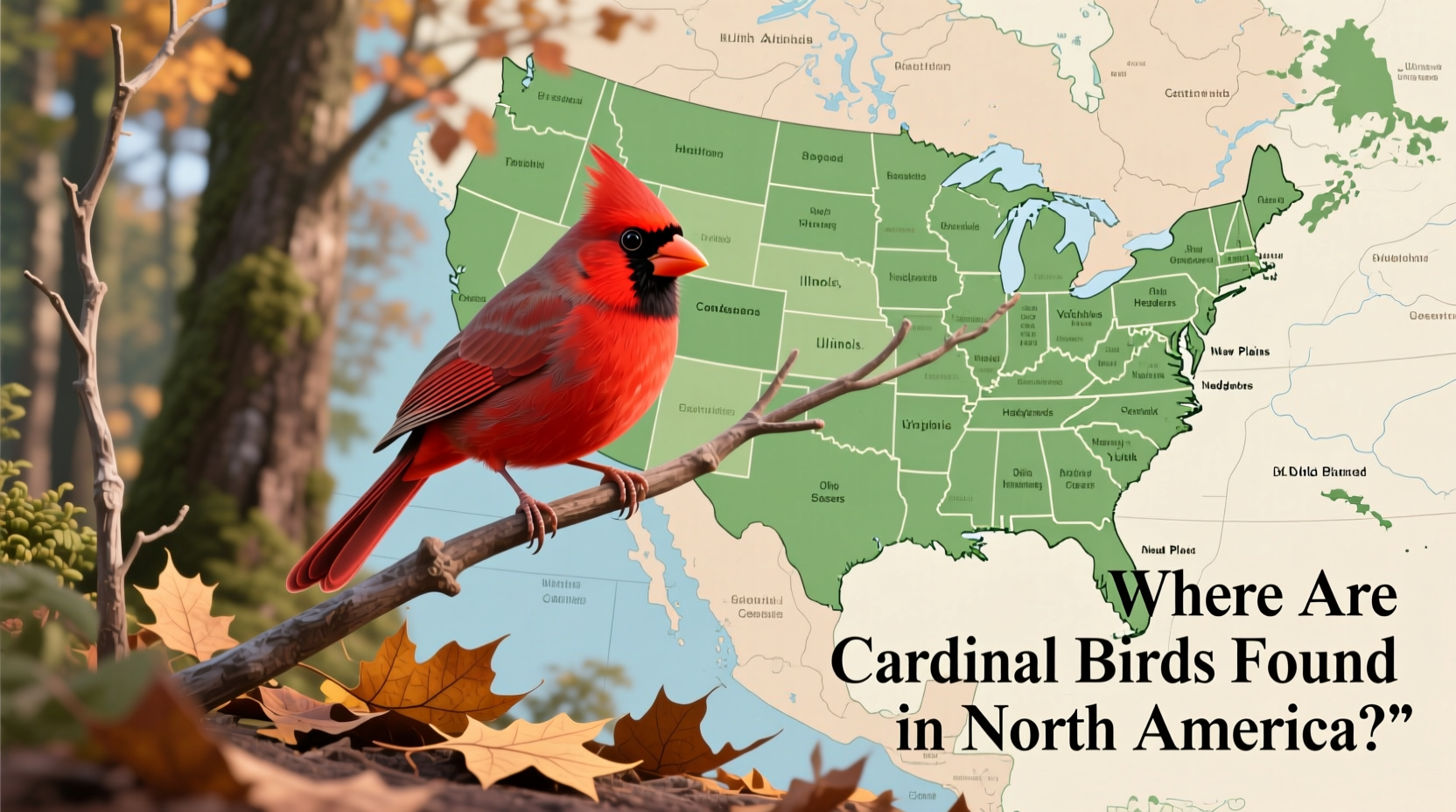

Cardinal birds are primarily found in the eastern and central regions of the United States, extending into parts of southeastern Canada and eastern Mexico. If you're wondering where are cardinal birds found, the answer lies in woodlands, gardens, shrublands, and suburban areas where dense vegetation provides shelter and food. The northern cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) is a non-migratory species, meaning it stays in its established territory year-round, which makes it a familiar sight in backyards from Texas to Maine.

Habitat and Geographic Range of Cardinal Birds

The northern cardinal has a well-defined geographic distribution that has expanded over the past century due to urbanization, backyard feeding, and climate shifts. Originally native to the southeastern United States, cardinals have steadily moved northward and westward. Today, their range spans from Maine in the northeast to Florida in the south, and as far west as Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and even into Arizona and New Mexico. In Canada, they can be seen regularly in southern Ontario, Quebec, and increasingly in southern Manitoba.

This expansion is largely attributed to human activityâparticularly the proliferation of bird feeders and the planting of ornamental shrubs and trees that mimic their preferred habitat. Cardinals thrive in edge habitats: areas where forests meet open spaces such as fields, roadsides, or residential neighborhoods. They prefer thickets, hedgerows, vine tangles, and evergreen cover, which offer protection from predators and harsh weather.

Preferred Environments for Cardinals

Understanding where cardinal birds are found requires examining the specific environmental conditions they favor. Cardinals are not deep-forest dwellers; instead, they flourish in transitional zones. These include:

- Suburban and urban yards with mature trees, shrubs, and reliable food sources like sunflower seeds.

- Riparian zonesâareas near rivers and streams with dense undergrowth. \li>Agricultural edges such as fence rows, overgrown fields, and woodland borders.

- Parks and cemeteries with abundant plant cover and minimal disturbance.

They avoid large, uninterrupted tracts of forest or wide-open grasslands without cover. Their need for dense vegetation explains why theyâre commonly spotted in residential areas where landscaping includes holly, dogwood, sumac, cypress, and other native or ornamental plants that provide both nesting sites and berries.

Seasonal Behavior and Year-Round Presence

One reason cardinals are so frequently observed is that they do not migrate. Unlike many songbirds that travel south for the winter, cardinals remain in their territories throughout the year. This means that if you live within their range, you can spot them in every seasonâwhether itâs a bright red male singing from a snow-covered branch in January or a pair building a nest in May.

In colder months, cardinals often form small family groups and may congregate at feeders. During breeding season (typically March through September), they become more territorial, with males defending their area through song and displays. Their loud, clear whistled callsâoften described as "what-cheer, what-cheer" or "birdie-birdie-birdie"âare a hallmark of early spring mornings.

Physical Identification and Sexual Dimorphism

When identifying where cardinal birds are found, visual recognition helps confirm their presence. The male northern cardinal is unmistakable: brilliant crimson plumage, a crest on its head, a black face mask around the bill, and a thick, cone-shaped red bill. Females, while less flashy, are equally distinctive with warm tan-brown bodies, reddish tinges on wings, tail, and crest, and the same facial markings and bill shape.

This sexual dimorphism plays a role in mating and social dynamics. Males use their coloration to attract mates and signal dominance, while femalesâ muted tones help them stay camouflaged while incubating eggs. Both sexes have crests they raise when excited or alarmed, and their flight pattern is bouncy and direct, typical of many finch-like birds.

Diet and Feeding Habits

Cardinals are omnivorous but predominantly granivorous, meaning they mainly eat seeds. However, their diet varies seasonally:

- Winter: Seeds from grasses, weeds, and commercial bird feeders (especially sunflower and safflower seeds).

- Spring and Summer: Insects, spiders, snails, and fruit in addition to seedsâimportant for feeding protein-rich meals to nestlings.

They forage on or near the ground, hopping through leaf litter or low branches. Providing a consistent food sourceâparticularly in winterâcan significantly increase your chances of attracting cardinals to your yard. Platform feeders or hopper feeders filled with black oil sunflower seeds are ideal.

| Region | Cardinal Presence | Best Time to Observe | Habitat Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern U.S. (e.g., Virginia, Georgia) | Year-round resident | All seasons; peak activity in early morning | Woodland edges, suburban gardens |

| Middle West (e.g., Illinois, Missouri) | Common and widespread | Winter (at feeders), Spring (singing males) | Fencerows, river bottoms |

| Southern Ontario, Canada | Established population | Year-round, especially snowy periods | Backyards, parks, forest margins |

| Southwestern U.S. (e.g., Arizona) | Localized, expanding | Late winter to early spring | Riparian corridors, irrigated landscapes |

| Western U.S. (e.g., California) | Rare or absent | N/A | No natural population; occasional escapees |

State Bird Status and Cultural Significance

The northern cardinal holds symbolic importance across much of its range. It is the official state bird of seven U.S. states: Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, North Carolina, Ohio, Virginia, and West Virginiaâmore than any other bird. This reflects its popularity, visibility, and cultural resonance.

In various traditions, seeing a cardinal is considered a sign of hope, renewal, or spiritual visitation. Some believe a cardinal sighting brings a message from a loved one who has passedâa notion popularized in poetry and folklore. While these beliefs are not scientific, they underscore the emotional connection people feel toward this vibrant bird.

Beyond symbolism, the cardinalâs striking appearance and melodic song make it a favorite among birdwatchers and photographers. Its frequent presence near human habitation allows for intimate wildlife encounters, contributing to its status as one of North Americaâs most beloved birds.

How to Attract Cardinals to Your Yard

If you want to know exactly where cardinal birds are found, start by making your own yard a suitable habitat. Here are proven strategies:

- Install a reliable bird feeder: Use platform or large hopper feeders filled with black oil sunflower seeds, safflower seeds, cracked corn, or white proso milletâfoods cardinals prefer.

- Provide water: A shallow birdbath with fresh water attracts cardinals for drinking and bathing, especially in winter if heated.

- Plant native shrubs and trees: Include species like Eastern red cedar, gray dogwood, spicebush, and trumpet vine to offer shelter and natural food sources.

- Avoid pesticides: Chemical-free yards support insect populations essential for young cardinals during breeding season.

- Preserve dense cover: Allow some areas of your yard to grow thickly; cardinals avoid open, exposed spaces.

Patience is keyâcardinals may take weeks or months to discover and trust a new feeding site, especially in areas with high predator activity.

Common Misconceptions About Cardinal Distribution

Several myths persist about where cardinal birds are found. One common misconception is that cardinals live everywhere in the U.S. In reality, they are rare or absent in much of the Pacific Northwest and the Rocky Mountains due to unsuitable habitat and climate. Another myth is that all red birds are cardinalsâhowever, species like the house finch or scarlet tanager can be mistaken for them, especially by novice observers.

Additionally, some assume cardinals migrate because they disappear in summer. In truth, males sing less during molting season (late summer), and families disperse after fledging, leading to reduced visibilityânot absence.

Conservation Status and Threats

The northern cardinal is currently listed as Least Concern by the IUCN Red List, with stable or increasing populations across most of its range. However, localized threats exist:

- Habitat loss due to urban sprawl and removal of native vegetation.

- Window collisionsâcardinals are prone to flying into glass, especially during breeding season when males attack their reflections.

- Climate change may shift suitable ranges northward, potentially displacing current populations.

- Avian diseases such as avian pox or salmonella outbreaks at crowded feeders.

To support conservation, maintain clean feeders (disinfect monthly), keep cats indoors, and advocate for green space preservation in your community.

Regional Differences in Cardinal Populations

While all northern cardinals belong to the same species, subtle regional variations exist. For example:

- Birds in the Deep South tend to have slightly darker plumage.

- Populations in drier southwestern regions rely more heavily on human-provided water and food.

- Urban cardinals may exhibit altered singing patterns to overcome noise pollution.

These adaptations highlight the speciesâ flexibility and resilience in diverse environments.

FAQs About Where Cardinal Birds Are Found

- Do cardinals live in Canada?

- Yes, northern cardinals are established in southern Ontario and parts of Quebec and Manitoba, particularly in urban and suburban areas with reliable food sources.

- Are cardinals found in California?

- No, cardinals are not native to California. Any sightings are typically escaped captive birds. The habitat and ecological niche are occupied by other species like the California towhee.

- Why donât I see cardinals in my neighborhood?

- Your area may be outside their natural range, or your yard might lack sufficient cover or food. Consider adding native shrubs and a dependable seed feeder.

- Do cardinals migrate?

- No, cardinals are non-migratory. They remain in the same general territory year-round, though young birds may disperse after fledging.

- What time of day are cardinals most active?

- Cardinals are most active at dawn and dusk. Early morning is the best time to hear males singing and observe feeding behavior.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4