Every winter, millions of birds embark on incredible journeys, migrating from colder northern regions to warmer climates where food is more abundant and survival conditions are favorable. This seasonal movement, known as winter bird migration, sees species such as warblers, swallows, hummingbirds, and many waterfowl traveling thousands of miles to reach their wintering grounds. Most North American migratory birds head southward, with common destinations including the southern United States, Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and even South America. Similarly, European and Asian birds often migrate to North Africa, the Middle East, or tropical parts of Asia. These patterns are driven by changes in daylight, temperature, and food availability, ensuring that birds can survive the harsh winter months.

The Science Behind Bird Migration

Bird migration is one of nature’s most remarkable phenomena. It involves complex navigation systems, physiological adaptations, and precise timing. Birds use a combination of celestial cues (like the position of the sun and stars), Earth’s magnetic field, and visual landmarks to find their way across continents. Some species, such as the Arctic Tern, travel over 40,000 miles annually—round-trip—from the Arctic to the Antarctic and back again.

Physiologically, birds prepare for migration by increasing fat stores through hyperphagia, a period of intense feeding. Their bodies undergo hormonal changes that trigger restlessness, known as Zugunruhe, which signals the onset of migratory behavior. The ability to fly long distances without rest is supported by highly efficient respiratory and circulatory systems, allowing for sustained aerobic activity.

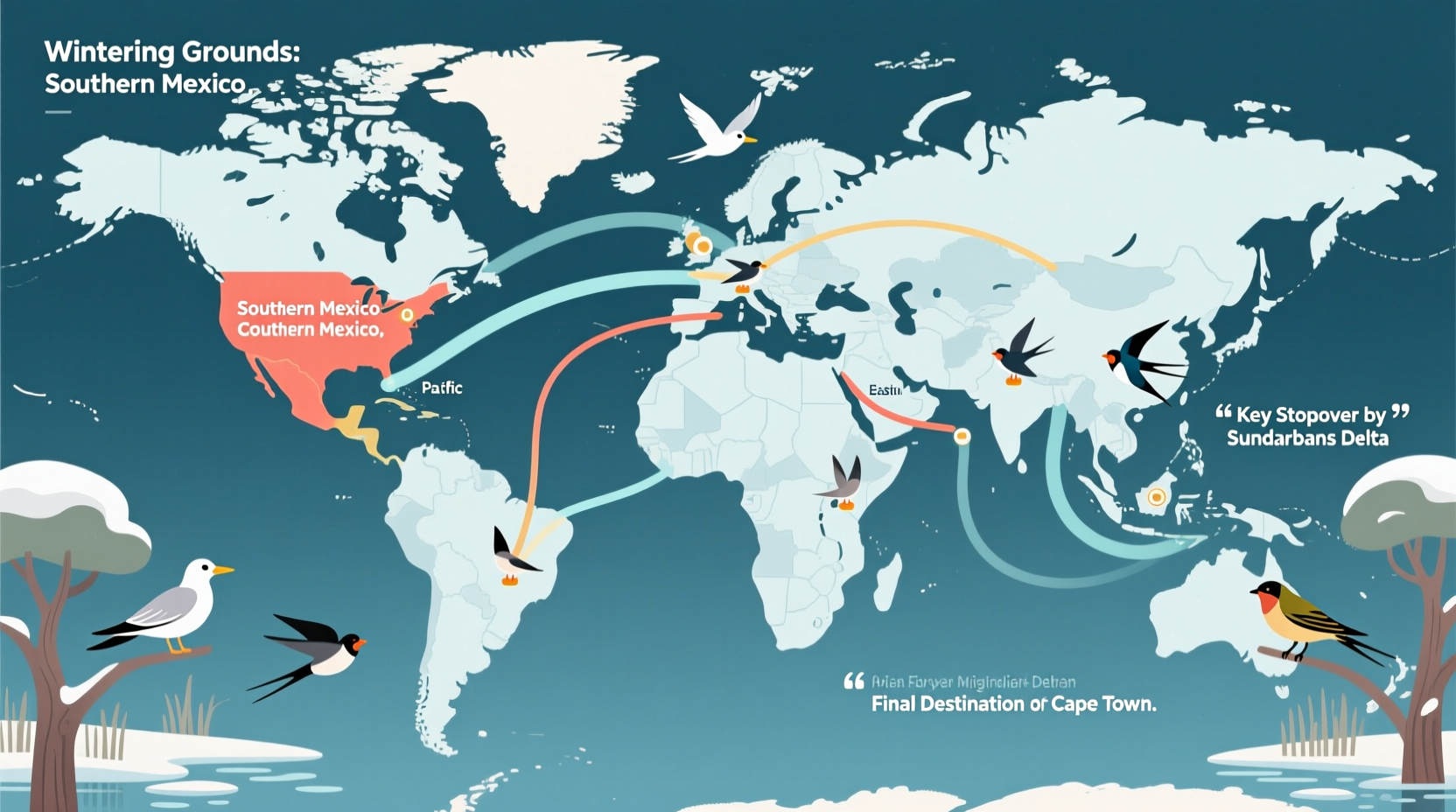

Major Migration Routes: Flyways Around the World

Birds follow established pathways called flyways—broad corridors used repeatedly each season. There are eight major global flyways:

- America’s Atlantic Flyway

- Mississippi Flyway

- Central Flyway

- Pacific Flyway

- Africa-Eurasian Flyway

- East Asia-Australasian Flyway

- Black Sea-Mediterranean Flyway

- South-South America Flyway

Each flyway connects breeding areas in temperate or polar zones with non-breeding winter habitats in subtropical or tropical regions. For example, ducks and geese using the Pacific Flyway may breed in Alaska and winter in California’s Central Valley or along the Mexican coast. Meanwhile, songbirds like the Wood Thrush leave northeastern U.S. forests and migrate through Central America to spend winter in Honduras or Nicaragua.

| Flyway | Key Species | Winter Destinations |

|---|---|---|

| Atlantic Flyway | Canada Goose, American Black Duck | Mid-Atlantic U.S., Florida, Caribbean |

| Mississippi Flyway | Tundra Swan, Mallard, Sandhill Crane | Louisiana, Texas, Mexico |

| Central Flyway | Whooping Crane, Snow Goose | Texas Panhandle, New Mexico, Northern Mexico |

| Pacific Flyway | Western Sandpiper, Dunlin, Greater White-fronted Goose | California, Baja California, Peru |

When Do Birds Migrate in Winter?

Migratory timing varies by species, latitude, and climate conditions. In general, fall migration begins in late August and continues through November, peaking in September and October. Spring return migration typically occurs from February to May. Short-distance migrants, like American Robins, may only move south within the U.S., while long-distance travelers, such as the Bobolink, fly from Canada all the way to Argentina.

Climate change has begun to alter these patterns. Warmer autumns have led some birds to delay departure, while others shift their winter ranges northward. Researchers monitor these changes using tools like eBird and radar tracking to understand how migration schedules are evolving.

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings of Bird Migration

Beyond biology, bird migration holds deep cultural significance across civilizations. In many Indigenous traditions, the arrival and departure of certain birds signal seasonal transitions and guide agricultural practices. For example, the return of swallows to San Juan Capistrano in California is celebrated annually and symbolizes renewal and faithfulness.

In literature and mythology, migrating birds often represent freedom, endurance, and spiritual journeying. The ancient Egyptians associated the soul’s passage to the afterlife with the flight of birds. In Japanese poetry, the cry of the migrating cuckoo evokes melancholy and impermanence. Even today, the sight of V-shaped flocks overhead stirs wonder and reminds us of nature’s interconnectedness.

How to Observe Winter Migrating Birds

Winter is an excellent time for birdwatching, especially in southern regions where migratory species congregate. Here are practical tips for spotting and identifying winter migrants:

- Visit Key Habitats: Coastal wetlands, estuaries, lakes, and marshes attract waterfowl and shorebirds. Forests and woodlands host thrushes, warblers, and sparrows.

- Use Binoculars and Field Guides: A good pair of binoculars (8x42 magnification recommended) enhances visibility. Pair it with a regional field guide or app like Merlin Bird ID.

- Go Early in the Day: Birds are most active during morning hours when they feed after cold nights.

- Listen for Calls: Many species are heard before seen. Learn common calls of ducks, herons, and songbirds.

- Join Local Birdwalks: Audubon chapters and nature centers often host guided winter birding tours.

Notable hotspots for observing winter migrants include Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge (New Mexico), Everglades National Park (Florida), and Point Reyes National Seashore (California). Internationally, places like Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary in India and the Camargue in France offer exceptional viewing opportunities.

Threats to Migratory Birds

Despite their adaptability, migratory birds face growing threats. Habitat loss due to urban development, agriculture, and deforestation disrupts both breeding and wintering sites. Climate change alters food availability and migration timing. Collisions with buildings, communication towers, and wind turbines kill millions annually. Light pollution disorients nocturnal migrants, leading to fatal crashes.

Conservation efforts are critical. Organizations like the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, BirdLife International, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service work to protect key habitats and promote bird-safe building designs. Individuals can help by keeping cats indoors, reducing pesticide use, installing bird-friendly windows, and participating in citizen science projects like Christmas Bird Counts.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Migration

Several myths persist about bird migration:

- Myth: All birds migrate. Reality: Only about 40% of bird species are migratory. Many, like chickadees and cardinals, remain in their home range year-round.

- Myth: Birds hibernate. Reality: No bird truly hibernates, though some, like the Common Poorwill, enter torpor—a state of reduced metabolic activity.

- Myth: Migration is random. Reality: Birds follow precise routes shaped by evolution and environmental cues.

- Myth: Feeding birds in winter stops them from migrating. Reality: Food at feeders supplements natural sources but doesn’t override biological triggers for migration.

Regional Differences in Winter Migration Patterns

Migratory behavior varies significantly by region. In North America, birds from Canada and the northern U.S. typically winter in the southern U.S., Mexico, or beyond. However, some species exhibit irruptive migration—unpredictable movements caused by food shortages—such as Pine Siskins or Snowy Owls appearing far south of their usual range.

In Europe, many birds from Scandinavia and Russia migrate to the Mediterranean basin or sub-Saharan Africa. In Asia, Siberian cranes travel to India’s Keoladeo National Park, while Japanese bush warblers disperse to southern islands and coastal China.

Urbanization and milder winters have also led to partial migration, where only some members of a population migrate. For instance, European Starlings in cities may stay put due to reliable food from human sources, while rural populations move south.

How You Can Support Migratory Birds

Supporting bird migration doesn’t require grand gestures. Simple actions make a difference:

- Plant native vegetation that provides berries, seeds, and shelter.

- Keep bird feeders clean and stocked with appropriate foods (sunflower seeds, suet, nectar).

- Turn off unnecessary lights at night during peak migration seasons (spring and fall).

- Advocate for green spaces and protected wetlands in your community.

- Report rare sightings to platforms like eBird to aid scientific research.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where do most North American birds go in the winter?

Most migratory birds from North America travel to the southern United States, Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, or northern South America, depending on species and breeding origin.

Do all birds migrate south for winter?

No. While many birds do fly south, some migrate east-west or altitudinally (from mountains to valleys). Others remain resident year-round if food and shelter are available.

What month do birds start migrating south?

Fall migration typically begins in late August, peaks in September and October, and tapers off by November, though exact timing depends on species and weather conditions.

How far do birds fly during winter migration?

Distances vary widely. Some birds fly just a few hundred miles, while others, like the Arctic Tern, travel over 40,000 miles round-trip annually between the poles.

Can climate change affect bird migration patterns?

Yes. Rising temperatures, shifting precipitation patterns, and earlier springs are altering migration timing, routes, and winter distributions. Some species now winter farther north than historically recorded.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4