Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, originates from strains of the influenza A virus that naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds such as ducks, geese, and shorebirds. These birds serve as the primary reservoirs for the virus, often carrying it without showing symptoms. The most concerning subtype, H5N1, has been responsible for widespread outbreaks in both wild and domestic bird populations since its emergence in the late 1990s. Understanding where bird flu comes from involves examining its biological origins, transmission pathways to poultry and occasionally humans, and the environmental and agricultural factors that contribute to its spread.

Biological Origins of Avian Influenza

The influenza A virus belongs to the Orthomyxoviridae family and is categorized by combinations of surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, but only a few—particularly H5 and H7—are associated with high pathogenicity in birds. Wild waterfowl, especially those in the orders Anseriformes (ducks, swans, geese) and Charadriiformes (shorebirds), carry low-pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) viruses in their respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts.

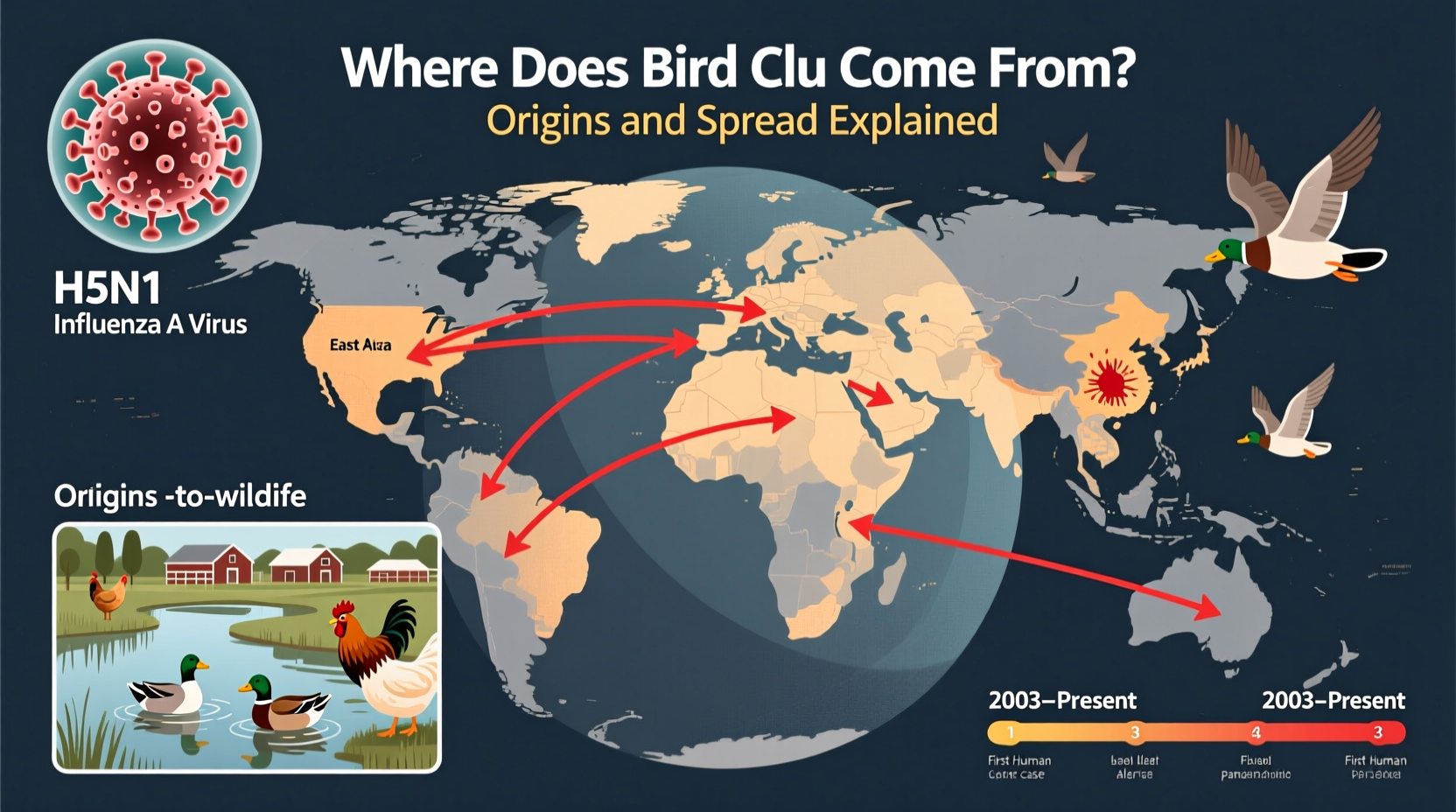

These natural hosts typically experience mild or no illness, allowing the virus to persist and evolve within global migratory bird populations. As these birds travel along flyways—established migration routes spanning continents—they can introduce avian influenza viruses to new regions. For example, the East Asian-Australasian Flyway and the Atlantic Flyway have both been linked to cross-border transmission events.

Evolution from Low- to High-Pathogenic Strains

While most avian influenza strains found in wild birds are low-pathogenic, they can mutate into highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) forms when introduced into domestic poultry flocks. This transformation usually occurs in environments with dense bird populations, such as commercial poultry farms or live bird markets, where rapid transmission allows for genetic drift and reassortment.

The H5N1 strain, first identified in farmed geese in Guangdong, China, in 1996, evolved into a highly virulent form by 1997, causing significant mortality in chickens and leading to the first documented human cases. Since then, multiple clades (genetic branches) of H5N1 have emerged, with some spreading globally through migratory birds and international trade in poultry products.

Transmission Pathways: From Wild Birds to Poultry

Direct contact between wild birds and domestic poultry is a major route of transmission. Backyard flocks, free-range operations, and farms near wetlands or migratory stopovers are particularly vulnerable. Contaminated water, feces, feathers, and equipment can all serve as vectors for the virus.

In addition, human activities such as improper disposal of infected carcasses, movement of live birds across regions, and inadequate biosecurity on farms amplify the risk of outbreaks. During peak migration seasons—typically spring and fall—the likelihood of spillover increases significantly, especially in temperate zones where wild and domestic bird habitats overlap.

| Factor | Role in Bird Flu Spread | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Migratory birds | Natural carriers; introduce virus to new areas | Monitor flyways; restrict poultry access to wetlands |

| Poultry farming practices | Facilitates mutation and amplification of virus | Enhance biosecurity; isolate flocks |

| Live bird markets | Hotspots for cross-species transmission | Implement hygiene protocols; regular testing |

| Climate change | Alters migration patterns and timing | Adapt surveillance systems seasonally |

Human Infection and Zoonotic Risk

Although bird flu primarily affects avian species, certain strains—including H5N1, H7N9, and H5N6—can infect humans, usually through close contact with infected birds or contaminated environments. Most human cases occur in individuals who handle sick poultry, work in slaughterhouses, or visit live bird markets.

As of 2024, there have been over 900 confirmed human cases of H5N1 worldwide, with a case fatality rate exceeding 50%. However, sustained human-to-human transmission remains rare, limiting pandemic potential—for now. Public health agencies like the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) closely monitor any mutations that could enhance transmissibility among people.

Global Outbreaks and Recent Trends

The current wave of HPAI, driven largely by the H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, began spreading rapidly in 2020 and reached unprecedented levels by 2022–2024. It affected millions of birds across Europe, North America, Africa, and Asia. In the United States alone, more than 90 million poultry were culled during the 2022 outbreak—one of the largest in history.

This strain has shown increased environmental stability and broader host range, infecting not only chickens and turkeys but also mammals such as foxes, seals, sea lions, and even dairy cattle in early 2024. The detection of H5N1 in U.S. dairy cows marked a significant shift, raising concerns about novel transmission routes and possible adaptation to mammalian hosts.

Environmental and Agricultural Factors Influencing Spread

Several interrelated factors influence where bird flu comes from and how it spreads:

- Agricultural intensification: Large-scale poultry operations increase density-related risks.

- Habitat encroachment: Expansion of farms into wetland areas brings domestic birds closer to wild reservoirs.

- Climate variability: Warmer temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns affect bird migration schedules and virus survival in the environment.

- International trade: Legal and illegal movement of birds and bird products can transport the virus across borders.

For instance, cold and moist conditions prolong the viability of the virus in soil and water, making winter and early spring high-risk periods in northern latitudes. Conversely, tropical regions may see year-round circulation due to stable climates and persistent wetland ecosystems.

Surveillance and Early Detection Systems

Effective prevention starts with robust surveillance. Many countries participate in global monitoring networks coordinated by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH). These programs rely on laboratory testing of dead wild birds, routine sampling in poultry farms, and real-time reporting of outbreaks.

Citizen scientists and birdwatchers also play a crucial role. Reporting unusual bird deaths—especially in waterfowl or raptors—through national hotlines or apps helps authorities respond quickly. In the U.S., the USDA’s National Wildlife Disease Program tracks avian influenza in wild populations, while state veterinary offices regulate farm-level responses.

Protecting Domestic Flocks: Best Practices for Farmers and Backyard Keepers

Whether managing a commercial operation or a small backyard flock, proactive biosecurity measures are essential:

- Isolate domestic birds: Prevent contact with wild birds by using enclosed coops and covered runs.

- Control access: Limit visitors, require protective clothing, and disinfect footwear and equipment.

- Source birds responsibly: Purchase from certified disease-free suppliers and quarantine new additions.

- Monitor health daily: Watch for signs like decreased egg production, swollen heads, or sudden death.

- Report suspicious cases immediately: Contact local animal health authorities at the first sign of illness.

During high-risk periods, consider suspending outdoor access for free-range birds and covering feed and water sources to prevent contamination.

Impacts on Wild Bird Populations and Conservation

While many wild birds tolerate avian influenza, HPAI strains can cause mass mortality events in susceptible species. In recent years, outbreaks have devastated colonies of gannets, puffins, albatrosses, and cranes. Seabirds, which often nest in dense aggregations, are especially vulnerable.

Conservationists warn that repeated epizootics (animal epidemics) could threaten already endangered species and disrupt ecosystem dynamics. Ongoing research aims to understand species-specific susceptibility and develop strategies to protect critical breeding sites without interfering with natural behaviors.

Public Health Recommendations for Bird Enthusiasts

Birdwatchers, researchers, and wildlife rehabilitators should take precautions during active outbreaks:

- Avoid handling sick or dead birds; if necessary, use gloves and masks.

- Disinfect binoculars, cameras, and clothing after visits to wetlands or poultry farms.

- Follow local advisories regarding trail closures or viewing restrictions.

- Do not feed waterfowl in areas with reported infections.

Organized birding groups should check updates from agencies like the Audubon Society or the British Trust for Ornithology before planning outings.

Debunking Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Misconception 1: "Bird flu is just like seasonal flu."

Reality: Avian influenza is biologically distinct and far more lethal in birds—and potentially in humans—than human-adapted flu strains.

Misconception 2: "You can get bird flu from eating chicken or eggs."

Reality: Properly cooked poultry and pasteurized egg products pose no risk. The virus is destroyed at temperatures above 70°C (158°F).

Misconception 3: "Only chickens get bird flu."

Reality: Over 100 bird species have tested positive, including raptors, songbirds, and seabirds.

Future Outlook and Research Directions

Scientists are exploring several avenues to mitigate the threat of avian influenza:

- Vaccination: While vaccines exist for poultry, widespread use is limited by cost, logistical challenges, and interference with disease surveillance (vaccinated birds may still shed virus).

- Genomic surveillance: Tracking viral evolution in real time helps predict emerging threats.

- One Health approaches: Integrating human, animal, and environmental health monitoring improves early warning capabilities.

Long-term solutions will require international cooperation, improved farming practices, and greater public awareness.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where does bird flu come from originally?

Bird flu originates in wild aquatic birds, particularly ducks and shorebirds, which carry the influenza A virus naturally without becoming ill.

Can humans catch bird flu from watching birds?

No, casual observation of birds, especially from a distance, does not pose a risk. Transmission requires direct contact with infected birds or their secretions.

Is it safe to go birdwatching during an outbreak?

Yes, if you follow guidelines: avoid touching birds or surfaces they’ve contacted, maintain distance, and practice hand hygiene.

How is bird flu different from regular flu?

Bird flu is caused by avian-specific influenza strains, primarily affects birds, and is much more deadly in avian populations than seasonal human flu.

What should I do if I find a dead bird?

Do not touch it. Report it to your local wildlife agency or department of natural resources for testing and safe removal.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4