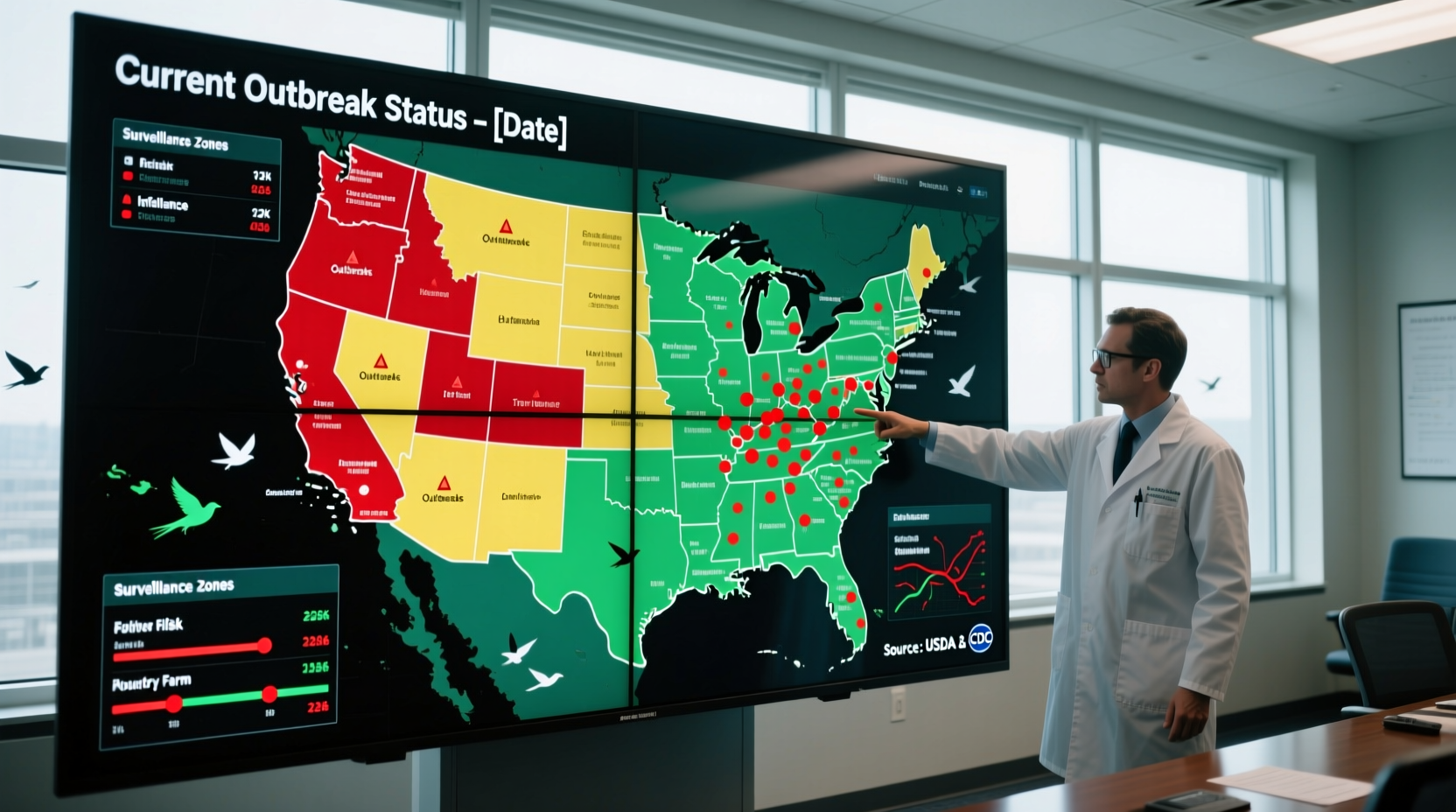

Bird flu, also known as highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), is currently present in multiple states across the United States, with confirmed cases reported in commercial poultry farms, backyard flocks, and wild bird populations. As of the most recent data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), HPAI has been detected in over 40 states, including major poultry-producing regions such as California, Iowa, Minnesota, and Texas. The virus continues to spread primarily through migratory wild birds, especially waterfowl like ducks and geese, which carry the virus without showing symptoms, making surveillance and containment challenging. For those asking 'where is bird flu in the US right now,' the answer varies by region and season, but ongoing outbreaks have been documented throughout 2023 and into early 2024.

Understanding Avian Influenza: A Biological Overview

Avian influenza is caused by Type A influenza viruses that naturally circulate among birds. These viruses are categorized by their pathogenicity—how severe the disease they cause can be. The current strain affecting the U.S., H5N1, is classified as highly pathogenic, meaning it spreads rapidly and causes high mortality rates in domestic poultry. While wild birds often serve as asymptomatic carriers, domesticated birds such as chickens, turkeys, and guinea fowl are highly susceptible and can die in large numbers once infected.

The virus spreads through direct contact with infected birds or contaminated secretions, including saliva, nasal discharge, and feces. It can also be transmitted indirectly via contaminated equipment, clothing, feed, or water. Because of this, biosecurity measures on farms and in backyard coops are essential for limiting transmission.

Geographic Spread and Regional Hotspots

As of early 2024, bird flu outbreaks have been confirmed in a wide range of U.S. states. The Midwest remains one of the hardest-hit regions due to its concentration of commercial poultry operations and its location along major migratory flyways. States like Iowa and Minnesota, leading producers of eggs and turkeys, have experienced repeated outbreaks since 2022. Similarly, the Central Valley of California, a critical wintering ground for migratory birds, has seen recurring infections in both wild and domestic birds.

In addition to these agricultural zones, coastal areas such as parts of Maine, Virginia, and South Carolina have reported cases linked to wild seabirds and raptors. Notably, bald eagles, gulls, and vultures have tested positive, indicating the virus is moving beyond waterfowl into predatory species—a concerning development for ecosystem health.

| State | First Confirmed Case (2022–2024) | Primary Affected Species | Outbreak Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iowa | February 2022 | Commercial egg-laying hens | Ongoing sporadic outbreaks |

| Minnesota | March 2022 | Turkeys, backyard chickens | Recurring spring/fall peaks |

| California | December 2022 | Wild waterfowl, commercial turkeys | Active monitoring in Central Valley |

| Texas | January 2023 | Backyard flocks, quail farms | Spikes during migration seasons |

| Maine | April 2023 | Bald eagles, gulls | Wildlife-focused outbreaks |

Seasonal Patterns and Migration Links

One of the key factors influencing where bird flu is spreading in the U.S. is the seasonal migration of wild birds. Each year, millions of waterfowl travel along four major flyways—the Pacific, Central, Mississippi, and Atlantic Flyways—carrying pathogens from breeding grounds in Canada and Alaska to wintering areas across the continental U.S.

Spring (March–June) and fall (September–November) are peak periods for new detections, coinciding with migration. During these times, surveillance efforts intensify, particularly in wetland-rich areas and near large poultry operations. However, unlike earlier patterns, some regions have reported year-round circulation, suggesting local environmental persistence of the virus in certain ecosystems.

Impact on Poultry Industry and Food Supply

The presence of bird flu in the U.S. has significant economic implications. Since 2022, more than 58 million birds have been culled to prevent further spread, according to USDA data. This includes entire flocks being depopulated even if only a few individuals test positive, following strict containment protocols.

These losses have led to temporary spikes in egg and turkey prices, though supply chains have generally stabilized due to rapid restocking and increased imports. Consumers may notice occasional shortages of specialty eggs (e.g., organic, free-range) in regions heavily affected by outbreaks.

It’s important to emphasize that properly cooked poultry and eggs remain safe to eat. The CDC confirms there is no food safety risk associated with consuming fully cooked chicken or eggs, even during active outbreaks.

Risk to Humans and Public Health Guidance

While avian influenza primarily affects birds, rare human infections have occurred globally, typically among individuals with prolonged, unprotected exposure to infected birds. In the U.S., only one mild human case was reported in 2022 (in Colorado, linked to culling activities), and no sustained human-to-human transmission has been documented.

The CDC considers the general public's risk to be low. However, people who work with or handle birds—farmers, veterinarians, wildlife rehabilitators—are advised to use personal protective equipment (PPE), including gloves, masks, and eye protection.

Symptoms in humans, if they occur, resemble mild flu: fever, cough, sore throat, and conjunctivitis. Anyone experiencing these after contact with sick or dead birds should seek medical attention and mention the exposure.

Role of Wild Birds and Conservation Concerns

Wildlife biologists are increasingly concerned about the impact of HPAI on native bird populations. Traditionally, avian flu had minimal effect on wild birds, but the current H5N1 strain has proven deadly for several non-waterfowl species. Mass die-offs have been recorded in American white pelicans, double-crested cormorants, and scavenging raptors like eagles and vultures.

This shift raises ecological alarms. Predatory and scavenging birds play vital roles in nutrient cycling and controlling disease in carcasses. Their decline could disrupt ecosystem balance. Additionally, endangered species such as the Hawaiian goose (nēnē) have been placed under heightened protection due to vulnerability.

What Birdwatchers Should Know

For birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts, the presence of bird flu adds a layer of responsibility. While the risk of contracting the virus from viewing birds at a distance is negligible, precautions are necessary when encountering sick or dead birds.

- Do not touch dead or visibly ill birds.

- Report sightings of five or more dead birds (especially waterfowl, raptors, or shorebirds) to your state wildlife agency or through the USGS National Wildlife Health Center’s online portal.

- Clean binoculars and gear regularly, especially after visiting wetlands or poultry farms.

- Avoid feeding birds in areas with known outbreaks, as feeders can concentrate birds and facilitate transmission.

Protecting Backyard Flocks

Backyard poultry owners are on the front lines of prevention. Simple biosecurity practices can dramatically reduce risk:

- Keep birds indoors during peak migration seasons if possible.

- Prevent contact with wild birds by enclosing coops and runs with netting.

- Disinfect shoes, tools, and tires before entering coop areas.

- Quarantine new birds for at least 30 days before introducing them to existing flocks.

- Source chicks and supplies from reputable, disease-free suppliers.

Many states offer free or low-cost testing for sick birds. Contact your local cooperative extension office for guidance.

Monitoring and Reporting Systems

Federal and state agencies maintain robust surveillance networks. The USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) coordinates national response efforts, while individual states manage localized reporting and control.

Real-time updates are available through:

- USDA APHIS HPAI Updates

- CDC Avian Influenza Portal

- USGS National Wildlife Health Center

- Your state’s department of agriculture or wildlife resources website

These platforms provide maps of current outbreaks, laboratory confirmation data, and biosecurity recommendations tailored to different audiences.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about avian influenza:

- Misconception: Eating chicken or eggs can give you bird flu.

Fact: Proper cooking destroys the virus. There is no foodborne risk. - Misconception: Only chickens get bird flu.

Fact: Over 100 bird species have tested positive, including songbirds, raptors, and seabirds. - Misconception: The virus spreads easily to humans.

Fact: Human cases are extremely rare and require close, prolonged contact with infected birds.

Future Outlook and Research Directions

Scientists are actively studying why this strain of H5N1 is more virulent and widespread than previous versions. One theory suggests viral evolution in wild bird reservoirs has increased environmental stability, allowing longer survival outside a host. Others point to climate change altering migration timing and routes, increasing overlap between wild and domestic populations.

Vaccine development for poultry is underway, but deployment faces challenges, including regulatory approval and logistical distribution. For now, prevention through biosecurity remains the primary defense.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Where is bird flu in the U.S. right now?

- As of early 2024, bird flu is present in over 40 states, with active outbreaks in the Midwest, California, Texas, and parts of the Northeast, primarily affecting poultry and wild birds.

- Can I still go birdwatching during an outbreak?

- Yes, observing birds from a distance poses no risk. Avoid touching sick or dead birds and report clusters of dead birds to authorities.

- Is it safe to eat eggs and poultry?

- Yes, as long as they are properly cooked. The virus is destroyed at normal cooking temperatures (165°F or 74°C).

- How does bird flu spread to backyard chickens?

- Through contact with wild birds, contaminated water, feed, or equipment, and even on the shoes or clothing of caretakers.

- What should I do if my chickens get sick?

- Isolate sick birds immediately, contact a veterinarian or your state’s animal health office, and follow quarantine procedures.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4