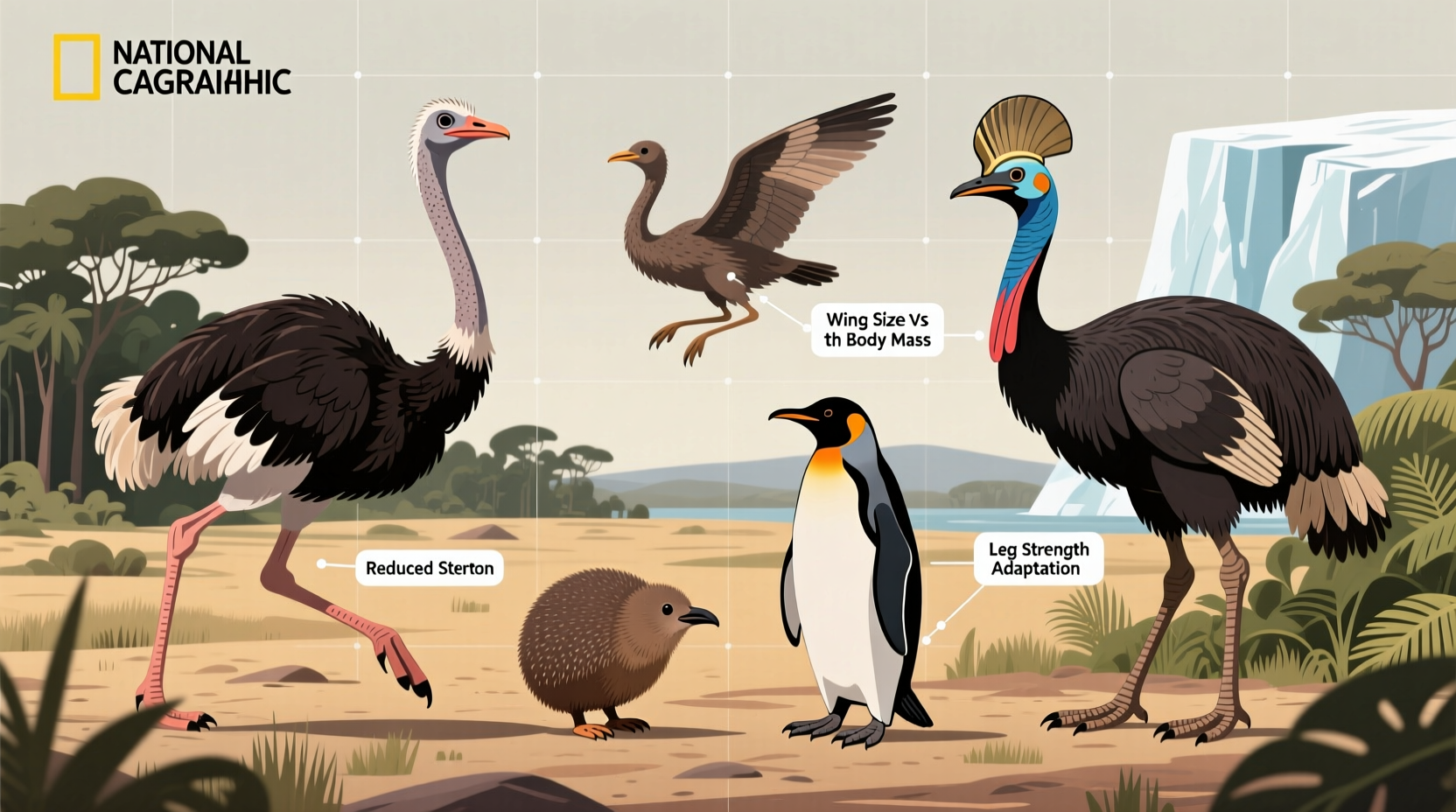

Many people wonder which birds cannot fly, and the answer includes well-known species such as penguins, ostriches, emus, and kiwis. These flightless birds have evolved unique adaptations that favor running, swimming, or survival in isolated environments over aerial mobility. A natural longtail keyword variant like 'what types of birds cannot fly' leads to a fascinating exploration of avian evolution, anatomy, and ecological niches. While most of the roughly 10,000 bird species can fly, around 60 are entirely flightless—a small but significant group that offers deep insight into how environment shapes physical traits.

Understanding Flightlessness in Birds

Flightlessness in birds is not a defect but an evolutionary adaptation. When birds inhabit environments with few predators and abundant food on the ground or in water, natural selection often favors energy conservation over the high metabolic cost of flight. Over generations, these birds develop heavier bodies, reduced wing structures, and stronger legs for alternative locomotion.

The loss of flight typically involves changes in skeletal structure—most notably, the reduction or absence of a keel on the sternum, which anchors flight muscles in flying birds. Without this anchor, pectoral muscles shrink, making powered flight impossible. This adaptation is seen across diverse species from different continents and ecosystems, suggesting convergent evolution driven by similar environmental pressures.

Major Groups of Flightless Birds

Flightless birds belong to several taxonomic groups, each with distinct evolutionary histories. Below is a breakdown of the primary categories:

| Bird | Native Region | Max Speed (if applicable) | Notable Traits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ostrich (Struthio camelus) | Africa | 70 km/h (43 mph) | Largest living bird; powerful legs for defense |

| Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae) | Australia | 50 km/h (31 mph) | Second tallest bird; excellent runner |

| Penguin (various species) | Southern Hemisphere (especially Antarctica) | Swims up to 15–36 km/h (9–22 mph) | Wings adapted for swimming; countershading camouflage |

| Kiwi (Apteryx spp.) | New Zealand | N/A (slow-moving) | Nocturnal; highly developed sense of smell |

| Cassowary (Casuarius spp.) | New Guinea, Australia | 50 km/h (31 mph) | Large casque; potentially dangerous claws |

| Takahe (Porphyrio hochstetteri) | New Zealand | Walking only | Rare; rediscovered after presumed extinction |

Ratites: The Classic Flightless Birds

Ratites are a clade of large, flightless birds that include ostriches, emus, rheas, cassowaries, and kiwis. They share certain anatomical features, such as a flat breastbone without a keel. Despite their similarities, genetic studies show they do not all descend from a single flightless ancestor—flight was lost independently multiple times within this group.

- Ostriches: Native to African savannas, ostriches are the fastest bipedal animals on land. Their wings are used for balance while running and in courtship displays.

- Emus: Found across Australia, emus migrate seasonally and can cover vast distances. They play a key role in seed dispersal.

- Rheas: South American relatives of ostriches, smaller in size, inhabiting grasslands and scrub forests.

- Cassowaries: Known as "the world's most dangerous bird," they inhabit tropical rainforests and have dagger-like claws capable of inflicting serious injury.

- Kiwis: Small, nocturnal, and covered in hair-like feathers, kiwis rely heavily on their sense of smell—an unusual trait among birds.

Penguins: Masters of Aquatic Flight

Though penguins cannot fly in the air, they are exceptional swimmers, using their modified wings as flippers to 'fly' through water. All 18–20 species of penguins are flightless and found exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere. The Emperor Penguin, the largest species, can dive deeper than 500 meters and hold its breath for over 20 minutes.

Penguins evolved flightlessness due to the rich marine resources available in cold southern waters and the lack of terrestrial predators on many sub-Antarctic islands. Their dense bones (unlike the hollow bones of flying birds) help with diving, and their streamlined bodies reduce drag.

Evolutionary Causes of Flightlessness

Why do some birds lose the ability to fly? Several factors contribute:

- Island Isolation: On remote islands with no mammalian predators, birds like the now-extinct moa of New Zealand and the dodo of Mauritius evolved flightlessness. With no need to escape threats, energy could be redirected toward reproduction and foraging.

- Energy Efficiency: Flight demands enormous energy. In stable environments, losing flight conserves calories, allowing birds to grow larger or invest more in offspring.

- Alternative Locomotion: Some birds traded flight for speed (ostrich), swimming (penguin), or stealth (kiwi).

- Sexual Selection: In some species, elaborate plumage or behaviors replaced flight as a means of attracting mates.

However, flightlessness comes with risks. When humans introduced predators like rats, cats, and dogs to islands, many flightless species went extinct rapidly. The dodo, hunted and outcompeted, disappeared by the late 17th century.

Modern Threats and Conservation Efforts

Today, many flightless birds are endangered. Habitat destruction, invasive species, and climate change threaten their survival. Conservation programs focus on predator control, habitat restoration, and captive breeding.

- New Zealand’s Department of Conservation runs successful initiatives to protect kiwis and takahē using fenced sanctuaries and public education.

- Penguin colonies in Antarctica and coastal regions face challenges from warming oceans reducing krill populations.

- Captive breeding has helped revive populations of the kākāpō, a flightless parrot, though it remains critically endangered.

If you're interested in seeing flightless birds in person, consider visiting wildlife reserves or zoos accredited by conservation organizations. Always verify ethical standards before supporting any facility.

Where to See Flightless Birds in the Wild

Observing flightless birds in their natural habitats offers a profound experience. Here are some top destinations:

- Southern Africa: Look for ostriches in national parks like Kruger or Etosha.

- Tasmania and Australia: Emus roam freely in rural areas; guided tours offer safe viewing.

- New Zealand: Stewart Island and protected sanctuaries provide chances to hear kiwis at night.

- Patagonia, Argentina/Chile: Greater rheas inhabit open grasslands.

- Antarctica and Subantarctic Islands: Home to emperor, Adélie, and king penguins. Access requires specialized eco-tours.

When planning a trip, check seasonal patterns. For example, penguin breeding seasons vary by species—Adélies arrive in October, while emperors breed during Antarctic winter (March–April). Always follow local guidelines to minimize disturbance.

Common Misconceptions About Flightless Birds

Several myths persist about non-flying birds:

- Myth: All flightless birds are large. Reality: Kiwis and wekas are relatively small, showing size isn’t a prerequisite for flightlessness.

- Myth: Flightless birds are slow to evolve. Reality: They adapt quickly when conditions change—but often too slowly to survive human-introduced threats.

- Myth: Penguins are mammals because they swim. Reality: Penguins are birds, warm-blooded, egg-laying, and feather-covered—despite their aquatic lifestyle.

- Myth: If a bird has wings, it must be able to fly. Reality: Wings serve other purposes—balance, display, swimming, and thermoregulation.

How to Support Flightless Bird Conservation

You don’t need to travel far to make a difference. Here are practical steps:

- Donate to reputable wildlife organizations like the World Wildlife Fund or BirdLife International.

- Volunteer locally or abroad with conservation projects focused on native species.

- Avoid products linked to deforestation or illegal wildlife trade.

- Educate others about the importance of biodiversity and the vulnerability of flightless species.

- Choose responsible tourism operators who follow ethical wildlife viewing practices.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What are some examples of birds that cannot fly?

- Examples include ostriches, emus, penguins, kiwis, cassowaries, rheas, and the takahe. Each has adapted to its environment in unique ways that make flight unnecessary.

- Why did certain birds lose the ability to fly?

- Birds lost flight primarily due to isolation on predator-free islands, abundance of ground resources, and evolutionary pressure to conserve energy. Over time, physical changes made flight impossible.

- Can any flightless birds swim instead of fly?

- Yes, penguins are flightless birds that use their wings to swim efficiently underwater, essentially 'flying' through water rather than air. They are among the most adept aquatic birds.

- Are there any flightless birds in North America?

- Currently, there are no naturally occurring flightless birds native to mainland North America. However, some domesticated breeds like certain chickens or turkeys have limited flight capability.

- How many species of flightless birds exist today?

- Approximately 60 extant species of birds cannot fly. This number fluctuates slightly depending on taxonomic classification, but includes ratites, penguins, and several island endemics.

In summary, understanding which birds cannot fly opens a window into evolutionary biology, ecological adaptation, and conservation science. From the towering ostrich to the elusive kiwi, these remarkable creatures challenge our assumptions about what it means to be a bird. Whether you're a casual observer or an aspiring ornithologist, learning about flightless birds enriches your appreciation of nature’s diversity and resilience.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4