Bird poop is white because birds excrete waste in the form of uric acid, which appears as a thick, chalky white paste. Unlike mammals that separate urine and feces, birds combine both solid and liquid waste into a single expulsion through their cloaca. This unique biological adaptation conserves water, a critical function for flight and survival. A natural longtail keyword variant such as 'why is bird droppings white instead of yellow' helps clarify this common curiosity rooted in avian physiology.

The Biological Reason Behind White Bird Poop

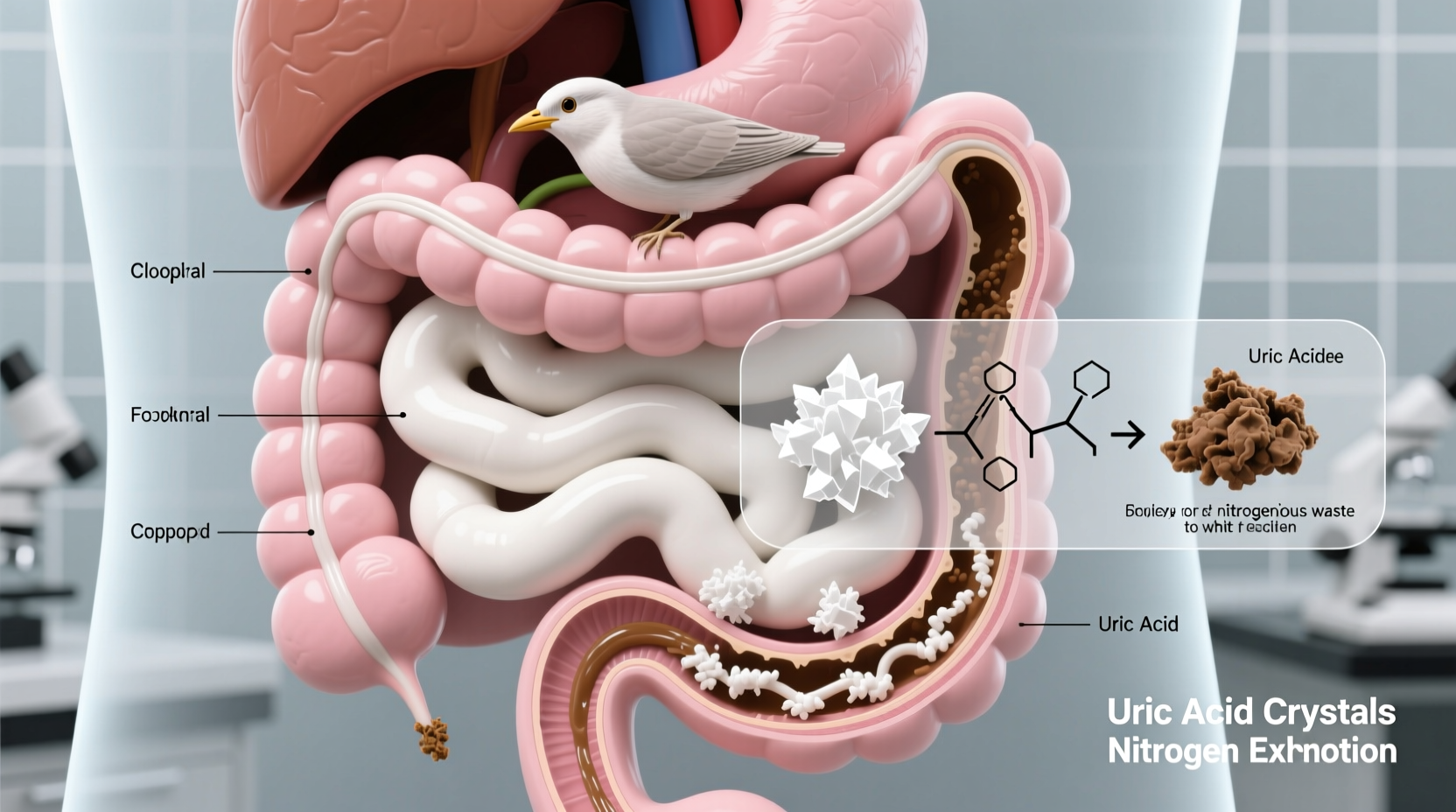

Birds do not produce urine in the same way mammals do. Instead of converting nitrogenous waste into urea (which dissolves in water and exits as yellow urine), birds convert it into uric acid. This compound is less toxic and requires far less water to expel. As a result, uric acid forms a semi-solid, white slurry that clings to surfaces—commonly seen on cars, sidewalks, and statues.

This metabolic process is highly efficient for animals designed for flight. Carrying excess water weight would hinder mobility, so minimizing fluid loss is essential. The white portion of bird droppings is primarily composed of uric acid crystals, while the darker central mass consists of digested food remnants—the actual fecal matter.

Understanding why bird poop is white leads directly to appreciating how avian biology supports energy efficiency, hydration management, and environmental adaptation. It’s not just a quirky fact; it reflects millions of years of evolutionary refinement.

Comparative Anatomy: Birds vs. Mammals

To fully grasp why bird poop appears white, it's helpful to compare avian and mammalian excretory systems. Mammals, including humans, rely on kidneys to filter blood and produce urea, which dissolves in water to form liquid urine. This solution allows for easy elimination but demands consistent access to hydration.

In contrast, birds have evolved a more water-conserving method. Their kidneys still filter waste, but the end product shifts from urea to uric acid through a process called uricotelism. Uric acid precipitates out of solution quickly, forming a paste rather than a liquid. This adaptation reduces dehydration risk—especially crucial during long flights or in arid environments.

The cloaca, a multi-purpose opening used for digestion, reproduction, and excretion, serves as the final exit point for both uric acid and feces. When a bird defecates, these components are expelled together, creating the familiar splat with a white cap and dark core.

Composition of Bird Droppings: What Makes Up the Splat?

A typical bird dropping consists of three main components:

- Uric acid (white portion): The primary nitrogenous waste product, appearing as a milky-white coating.

- Fecal matter (dark center): Composed of undigested food particles, bacteria, and bile pigments, varying in color based on diet.

- Mucus: Secreted by the intestinal tract to aid in smooth passage through the cloaca.

The ratio of white to dark material can vary depending on species, hydration levels, and recent meals. For example, seed-eating birds like pigeons may produce droppings with a higher proportion of white uric acid, while fruit-eating birds such as toucans might show more colorful fecal cores due to pigment retention.

Interestingly, the consistency and appearance of droppings can serve as health indicators for ornithologists and avian veterinarians. Abnormal colors—such as greenish urates or bloody feces—may signal infection, liver dysfunction, or dietary imbalance.

Dietary Influence on Dropping Appearance

While the white component remains relatively consistent across species, the fecal part of bird poop varies significantly based on what a bird eats. Observing droppings can provide valuable insights into feeding habits and ecological roles.

For instance:

- Birds consuming berries (e.g., robins, waxwings) often leave droppings with red, purple, or black stains.

- Fish-eating birds like ospreys or herons may produce greasy, grayish feces with visible bone fragments.

- Insectivorous birds such as swallows tend to have small, dark droppings with minimal residue.

This variation is useful for field researchers conducting non-invasive studies. By analyzing droppings near nests or roosting sites, scientists can infer diet composition without disturbing the animals.

For casual observers, noticing changes in local bird droppings after seasonal migrations or new feeders appear can also reveal shifts in bird populations or feeding behaviors.

Evolutionary Advantages of White Bird Poop

The evolution of uric acid excretion offers several advantages beyond water conservation:

- Reduced weight during flight: Eliminating the need to carry liquid waste improves aerodynamic efficiency.

- Nest hygiene: Precipitated uric acid is less likely to seep into nesting materials compared to liquid urine, helping prevent bacterial growth and parasite infestation.

- Camouflage and signaling: Some researchers suggest that the bright white splash may deter predators by mimicking mold or mineral deposits, though this theory lacks strong empirical support.

Additionally, hatchlings in altricial species (those born helpless) often encase their feces in mucous membranes called fecal sacs, which parents remove to keep nests clean. These sacs contain the same uric acid base but are easier to transport externally.

Cultural and Symbolic Interpretations of Bird Droppings

Across cultures, bird droppings carry diverse symbolic meanings—often tied to chance, luck, or divine messages. In many European traditions, being hit by bird poop is considered a sign of good fortune, possibly stemming from the rarity of the event or its association with abundance (birds being numerous and widespread).

In some Asian countries, particularly Japan, there’s a popular belief that if bird droppings land on you, wealth or unexpected prosperity is imminent. This superstition has even inspired novelty merchandise and humorous greeting cards.

Conversely, in practical urban settings, bird droppings are viewed as unsanitary and corrosive. Accumulated guano can damage paintwork on vehicles, erode stone architecture, and pose health risks if inhaled in large quantities (e.g., histoplasmosis from dried pigeon droppings in attics).

Despite these concerns, the cultural fascination persists. Street artists sometimes incorporate bird droppings into time-lapse photography projects, symbolizing unpredictability and nature’s indifference to human constructs.

Health and Safety Considerations

While generally harmless in small amounts, bird droppings can harbor pathogens under certain conditions. Key risks include:

- Salmonella: Can be transmitted through contaminated surfaces, especially in areas where poultry or pet birds are kept.

- Avian influenza: Though rare, direct contact with infected secretions poses a transmission risk.

- Histoplasmosis: Caused by a fungus (Histoplasma capsulatum) that grows in soil enriched with bird droppings, particularly from starlings and pigeons.

To minimize risk:

- Avoid stirring up dust in areas with heavy guano buildup.

- Wear gloves and masks when cleaning large accumulations.

- Wash hands thoroughly after outdoor activities in bird-populated zones.

- Keep playground equipment and outdoor dining areas covered when not in use.

Pet owners should also monitor backyard flocks or cage birds for abnormal droppings, as sudden changes may indicate illness.

Observational Tips for Birdwatchers

For serious birdwatchers and citizen scientists, learning to interpret droppings enhances observational skills. Here are practical tips:

- Use droppings to locate roosts: Dense clusters of white splats beneath trees or eaves often indicate regular sleeping sites, especially for nocturnal species like owls or communal sleepers like starlings.

- Identify species indirectly: Large,ropy droppings with wing-shaped splatter patterns typically come from raptors; tiny dots are likely from songbirds.

- Track migration: Seasonal appearance of unfamiliar droppings (e.g., orange-stained pellets) may signal arrival of migratory species.

- Assess habitat quality: High concentration of droppings in one area could mean abundant food sources—or overcrowding and stress.

Pair visual analysis with audio recordings and camera traps for richer data collection.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Poop

Several myths persist about bird droppings, often fueled by anecdotal stories or incomplete understanding:

- Misconception: The white part is urine.

Clarification: While analogous to urine in function, it is chemically distinct—uric acid, not liquid urea. - Misconception: All birds produce identical droppings.

Clarification: Diet, size, metabolism, and species all influence shape, size, and coloration. - Misconception: Bird poop is always acidic and damages surfaces immediately.

Clarification: While prolonged exposure can degrade paint or metal, short-term contact is usually benign. Quick washing prevents most issues.

Educating the public on these points fosters better coexistence with urban wildlife.

Environmental Impact and Guano Use

Bird droppings, collectively known as guano, have played significant roles in agriculture and ecology. Historically, seabird guano from coastal islands was harvested extensively in the 19th century as a potent fertilizer rich in nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium.

Today, guano mining is regulated to protect nesting colonies, but organic farmers still use processed bat and seabird guano as sustainable soil amendments. Its slow-release nutrients benefit crops without chemical runoff.

In natural ecosystems, guano contributes to nutrient cycling, particularly on isolated islands where few other decomposition pathways exist. However, overpopulation of gulls or pigeons in cities can lead to excessive nutrient loading in waterways, contributing to algal blooms.

| Bird Type | Dropping Characteristics | Common Locations |

|---|---|---|

| Pigeon | Large, white-heavy with dark center | Urban rooftops, statues, bridges |

| Sparrow | Small, dotted patterns | Gutters, window sills |

| Owl | White wash with regurgitated pellet nearby | Tree cavities, barns |

| Seagull | Watery splatter, wide dispersion | Beaches, parking lots |

| Hawk | Streamers with elongated tail | Power lines, tall trees |

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is bird poop white and not yellow like mammal urine?

Birds excrete nitrogenous waste as uric acid, a white paste that requires little water, unlike mammals that excrete urea dissolved in water (urine).

Is bird poop harmful to humans?

In most cases, no. However, accumulated droppings can harbor fungi or bacteria, so avoid inhaling dust from dry guano and practice good hygiene.

Do all birds have white poop?

Most birds produce white uric acid deposits, but the amount and visibility depend on species, diet, and hydration.

Can you tell what a bird eats by its droppings?

Yes. The color and texture of the fecal portion reflect diet—berries cause reddish stains, insects yield dark specks, and fish result in oily residues.

Does rain wash away bird poop easily?

Fresh droppings can be rinsed off with water, but dried guano adheres strongly and may require gentle scrubbing to prevent surface damage.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4