Birds don't get electrocuted on power lines because they don't complete an electrical circuit—a key reason why small animals can safely perch on high-voltage wires without harm. This phenomenon, often summed up in queries like 'why do birds not get electrocuted on wires,' is rooted in basic principles of electricity and animal physiology. When a bird lands on a single wire, its body reaches the same electrical potential as the wire, but since it's not touching another wire or a grounded surface, current doesn’t flow through it. This simple yet vital concept explains why you’ll commonly see birds lined up on transmission lines with no risk of shock.

The Science Behind Why Birds Can Safely Perch on Wires

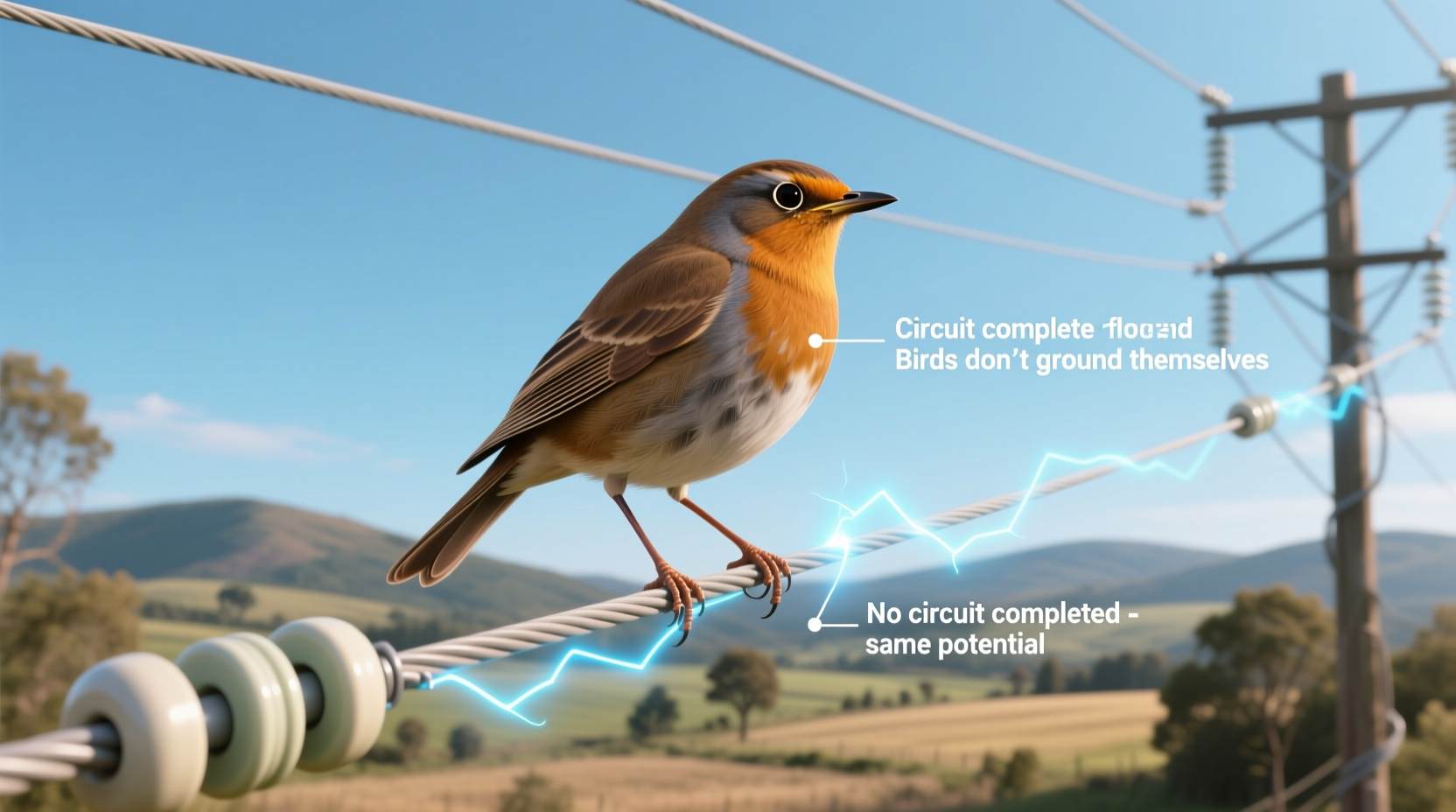

Understanding why birds don't get electrocuted on wires requires a foundational grasp of how electricity travels. Electricity always seeks the path of least resistance from a high-voltage area to a lower one—typically ground. For current to flow through a conductor (including living tissue), there must be a difference in electrical potential between two points. A bird sitting on a single power line touches only one point in the circuit. Because both of its feet are on the same wire, there's minimal voltage difference across its body, so very little or no current flows through it.

This principle is known as equipotential perching. As long as the bird remains isolated from other conductive paths—such as a second wire with different voltage or a grounded pole—it will not experience an electric shock. The current continues along the wire, which offers far less resistance than the bird’s body.

When Birds *Can* Be Electrocuted: Understanding the Risks

While perching on a single wire is safe, birds can and sometimes do get electrocuted when they bridge two wires at different voltages or touch a live wire while contacting a grounded structure. Large birds—such as eagles, hawks, owls, and vultures—are especially vulnerable due to their wide wingspans. If a raptor takes off from or lands on a utility pole and simultaneously touches a live wire and a neutral or grounded part (like a transformer or pole), it creates a path for current to flow through its body, resulting in electrocution.

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, thousands of raptors are killed annually by power line electrocutions. This has prompted utility companies and conservationists to collaborate on retrofitting poles with insulation, increased spacing between conductors, and perch deterrents to reduce avian fatalities.

Biology Meets Physics: How Bird Anatomy Plays a Role

Birds’ anatomy also contributes to their safety on wires. Their legs are covered in thick, scaly skin that is relatively dry and non-conductive. Additionally, most small perching birds have short legs, minimizing the distance—and therefore the voltage difference—between their feet when standing on a single wire.

Even if a small amount of current were to pass between their feet, the resistance of their body tissues limits the flow. However, this protection disappears if the bird becomes wet (reducing skin resistance) or makes contact with multiple conductors. Wet conditions increase the risk, especially during rainstorms or heavy dew, when water can act as a conductive bridge.

Key Factors That Determine Avian Safety on Power Lines

- Single-wire contact: Safe; no circuit is completed.

- Contact with two wires: Dangerous; creates a path for current flow.

- Contact with wire and grounded object: Lethal; completes circuit to earth.

- Bird size and wingspan: Larger birds face higher risks due to greater reach.

- Environmental conditions: Rain, fog, or condensation can increase conductivity.

- Insulation and pole design: Modern infrastructure reduces risk through protective measures.

Cultural and Symbolic Interpretations of Birds on Wires

Beyond the physics, birds perched on power lines have captured human imagination across cultures. In literature and visual art, flocks of birds on wires often symbolize unity, communication, or the intersection of nature and technology. Photographers frequently capture these scenes to evoke themes of urban solitude or natural resilience amid industrial landscapes.

In some interpretations, the image of birds evenly spaced on a line represents harmony and balance—ironically mirroring the electrical equilibrium that keeps them safe. Others see it as a metaphor for modern life: individuals coexisting in close proximity without direct connection, much like people in digital society.

Filmmakers and poets have used this imagery to suggest transition, waiting, or contemplation. The stillness of birds on wires contrasts with the invisible energy flowing beneath them—an elegant duality between appearance and reality.

Practical Implications for Utility Companies and Conservation Efforts

While small songbirds rarely suffer from electrocution, larger species are at significant risk. Energy providers around the world have implemented avian protection plans to mitigate this issue. These include:

- Installing insulated covers on exposed connectors.

- Increasing separation between energized components.

- Using perch discouragers on dangerous parts of poles.

- Designing new poles with bird-safe configurations.

- Monitoring high-risk areas using camera systems.

In the United States, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act provide legal incentives for utilities to adopt bird-friendly practices. Some companies even partner with wildlife organizations to conduct audits and install retrofits in critical habitats.

| Bird Type | Risk Level | Primary Danger | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small songbirds (sparrows, starlings) | Very Low | Minimal; rarely bridge gaps | Natural behavior usually safe |

| Pigeons & doves | Low to Moderate | Contact with wet surfaces | Drip loops, insulation |

| Raptors (eagles, hawks) | High | Wingspan bridges conductors | Increased spacing, perch guards |

| Owls & vultures | High | Nocturnal landings on poles | Insulated transformers |

Common Misconceptions About Birds and Electricity

Several myths persist about why birds don’t get shocked on wires. One common misunderstanding is that birds are immune to electricity. This is false—they are just as susceptible as any animal if they complete a circuit. Another myth is that rubber-coated feet protect them. While some shoes have rubber soles, birds’ feet are not naturally insulated in a way that blocks high voltage. The real answer lies in circuit dynamics, not biology alone.

Some believe that all birds are safe on any wire. But this isn’t true—species size, posture, and environmental factors matter greatly. A wet crow spreading its wings near a transformer is in far more danger than a dry sparrow on a distant line.

Tips for Observing Birds on Power Lines Safely and Ethically

For birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts, power lines can offer excellent opportunities to observe flocking behavior, flight patterns, and species identification. However, it’s important to maintain a respectful distance and avoid disturbing roosting birds. Here are practical tips:

- Use binoculars or a spotting scope: Observe from a safe distance without disrupting birds.

- Avoid loud noises or sudden movements: Especially near nesting or roosting sites.

- Report injured or electrocuted birds: Contact local wildlife rehabilitators or utility companies.

- Support bird-safe infrastructure: Advocate for avian protection policies in your community.

- Photograph responsibly: Never bait birds or alter environments for better shots.

How You Can Help Reduce Avian Electrocutions

Individuals can contribute to bird safety around power infrastructure. If you notice dangerous pole designs—such as exposed connections or frequent large bird activity—report them to your local utility provider. Many companies have hotlines or online forms for such concerns.

You can also support conservation groups working on avian protection, such as the Raptor Research Foundation or the American Bird Conservancy. Participating in citizen science projects like eBird helps track population trends and identify high-risk zones.

Finally, educating others about why birds don't get electrocuted on wires—and when they might—is a powerful way to promote awareness. Sharing accurate information dispels myths and encourages safer engineering practices.

Conclusion: Balancing Nature and Infrastructure

The sight of birds perched on power lines is a familiar one, but the science behind their safety is anything but simple. The reason why birds don't get electrocuted on wires lies in the principles of electrical circuits, not supernatural immunity. By understanding the interplay between physics and biology, we gain deeper insight into both natural behavior and technological design.

As urban development expands and energy networks grow, protecting wildlife becomes increasingly important. Through thoughtful engineering, public awareness, and conservation partnerships, we can ensure that our infrastructure supports both human needs and ecological balance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why don't birds get shocked on power lines?

Birds don’t get shocked because they only touch one wire, so no electrical circuit is completed. Without a path to a lower voltage or ground, current doesn’t flow through their bodies.

Can birds get electrocuted on power lines?

Yes, birds can be electrocuted if they touch two wires at different voltages or contact a live wire while grounded. This is especially common in large birds with wide wingspans.

Why are larger birds more at risk?

Larger birds, like eagles and owls, have wider wingspans that can easily bridge the gap between energized components, creating a path for electric current to flow through their bodies.

Do wet conditions affect bird safety on wires?

Yes, wet feathers or damp surfaces can increase conductivity, raising the risk of shock if a bird contacts multiple conductors or a grounded structure.

What are utility companies doing to protect birds?

Utilities install insulated covers, increase spacing between wires, use perch deterrents, and redesign poles to minimize electrocution risks, especially in areas frequented by protected species.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4