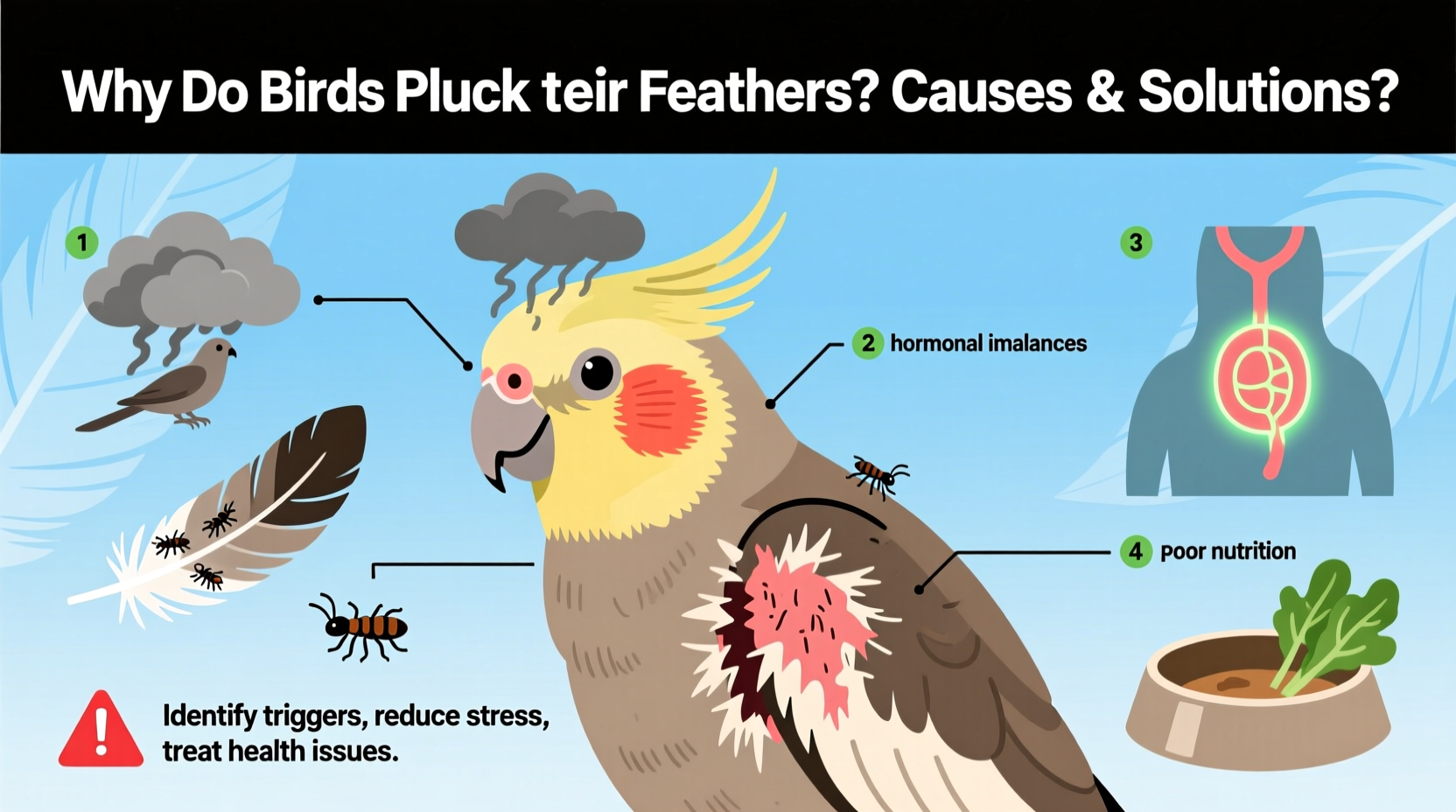

Birds pluck their feathers for a variety of reasons, ranging from natural molting processes to serious health or psychological issues. Understanding why do birds pluck their feathers is essential for bird owners and wildlife observers alike, as it helps distinguish between normal behavior and signs of distress. Feather plucking, also known as pterotillomania, can stem from medical conditions such as skin infections, parasites, hormonal imbalances, or nutritional deficiencies. Equally common are environmental and emotional triggers including stress, boredom, lack of stimulation, or changes in routine. In captivity, especially among parrots and other intelligent species, feather picking often reflects psychological discomfort due to isolation, anxiety, or improper socialization. Recognizing the underlying cause is critical to addressing the behavior effectively.

The Biology of Feathers and Molting

Feathers are complex structures made primarily of keratin, the same protein found in human hair and nails. They serve multiple functions: insulation, flight, waterproofing, and communication through color and display. Birds naturally shed and replace feathers in a process called molting, which typically occurs once or twice a year depending on the species. During molting, old or damaged feathers are lost systematically, and new ones grow in their place. This is not considered plucking, as it’s a controlled, cyclical process regulated by hormones and influenced by daylight duration and seasonal changes.

Molting patterns vary widely across species. For example, canaries and finches undergo a complete molt annually, while larger parrots like macaws may take up to two years to fully replace all feathers. During healthy molting, you might notice small amounts of feather loss and pin feathers—new feathers encased in a waxy sheath—emerging evenly across the body. It's important not to confuse this with excessive plucking, where large patches of bare skin appear, often around the chest, legs, or under the wings.

Medical Causes of Feather Plucking

When birds excessively remove their feathers beyond normal molting, a veterinary evaluation is crucial. Several medical conditions can prompt self-plucking:

- Skin infections: Bacterial or fungal infections can cause itching and irritation, leading birds to scratch or pull at affected areas.

- Parasites: Mites, lice, and internal parasites such as giardia can contribute to discomfort and feather damage.

- Nutritional deficiencies: A diet lacking in essential vitamins (especially vitamin A) or fatty acids can weaken feather structure and lead to poor plumage health.

- Hormonal imbalances: Conditions like hypothyroidism or reproductive disorders may trigger abnormal behaviors including feather destruction.

- Pain or inflammation: Arthritis or internal pain may cause birds to focus attention on nearby feathered areas, resulting in localized plucking.

Veterinarians use blood tests, skin scrapings, feather analysis, and dietary assessments to diagnose underlying health problems. Treating the root medical issue often resolves the plucking behavior, especially when caught early.

Psychological and Environmental Triggers

In captive birds, particularly intelligent species like African greys, cockatoos, and Amazons, feather plucking is frequently linked to psychological distress. These birds have high cognitive needs and form strong emotional bonds. When deprived of mental stimulation or social interaction, they may resort to self-destructive behaviors.

Common environmental stressors include:

- Lack of daily interaction or companionship

- Inadequate cage size or barren environments

- Exposure to loud noises, predators, or household pets

- Irregular lighting or sleep cycles

- Sudden changes in routine or habitat

Boredom is a major contributor. Birds evolved to spend hours foraging, flying, and interacting socially. A caged bird without toys, puzzles, or opportunities for exploration may develop compulsive habits like over-preening or feather pulling. This behavior can become habitual even after the initial stressor is removed, similar to obsessive-compulsive disorder in humans.

Captive vs. Wild Bird Behavior

Feather plucking is far more common in captive birds than in wild populations. In nature, birds face challenges, but they also enjoy constant activity, social flocks, and environmental complexity. Captivity often restricts these natural behaviors, increasing the risk of psychological imbalance.

Wild birds may lose feathers due to predation attempts, fights, or parasites, but systematic self-plucking is rare. When observed in wild individuals, it may indicate disease exposure or severe environmental disruption such as pollution or habitat loss. Conservationists sometimes monitor feather condition in wild populations as an indicator of ecosystem health.

For pet owners, replicating natural conditions is key. Providing foraging opportunities (e.g., hiding food in puzzle toys), allowing supervised out-of-cage time, and maintaining a predictable daily schedule can significantly reduce stress-related plucking.

Diet and Nutrition: A Foundational Factor

Diet plays a central role in feather health. Many commercial seed mixes are high in fat and low in essential nutrients, contributing to poor feather quality and skin problems. Seeds alone should not constitute more than 30–50% of a bird’s diet.

A balanced avian diet includes:

- Fresh vegetables (e.g., leafy greens, carrots, broccoli)

- Fruits (in moderation due to sugar content)

- High-quality pelleted food formulated for the species

- Occasional protein sources (e.g., cooked eggs, legumes)

Vitamin A deficiency, common in seed-fed birds, leads to dry, flaky skin and weakened feather follicles. Omega-3 fatty acids support healthy skin and reduce inflammation. Consultation with an avian veterinarian can help tailor a nutrition plan specific to your bird’s species and age.

| Common Cause | Signs | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Molting | Even feather loss, pin feathers present, no skin damage | Support with proper nutrition and humidity |

| Boredom/Stress | Feather loss on chest/torso, repetitive motions | Enrich environment, increase social interaction |

| Nutritional Deficiency | Dull, brittle feathers, flaky skin | Improve diet with pellets, veggies, supplements |

| Parasites/Infection | Itching, redness, scabs, odor | Veterinary treatment with meds or antifungals |

| Hormonal Issues | Seasonal plucking, behavioral changes | Vet assessment, possible hormone therapy |

How to Prevent and Manage Feather Plucking

Prevention begins with creating a stimulating, stable environment. Here are practical steps bird owners can take:

- Provide daily mental enrichment: Rotate toys, introduce foraging activities, and teach simple tricks using positive reinforcement.

- Ensure adequate social interaction: Spend quality time talking, playing, or training your bird every day.

- Maintain a consistent routine: Birds thrive on predictability—keep feeding, lighting, and interaction times regular.

- Optimize living space: Use appropriately sized cages with perches of varying textures and materials to promote foot health and movement.

- Monitor for early warning signs: Slight feather ruffling, reduced preening, or irritability may precede full-blown plucking.

If plucking has already begun, avoid punitive measures. Yelling or isolating the bird will increase stress. Instead, identify and remove potential triggers. Some owners use collars temporarily to prevent access to feathers, but these should only be used under veterinary guidance and never as a long-term solution.

Myths and Misconceptions About Feather Plucking

Several myths persist about why birds pluck their feathers:

- Myth: Birds pluck because they hate their owners.

Reality: Plucking is rarely personal; it’s usually a response to unmet physical or emotional needs. - Myth: Only caged birds pluck feathers.

Reality: While less common, wild birds can exhibit feather damage under extreme stress or illness. - Myth: All feather loss is harmful.

Reality: Normal molting is healthy and necessary for feather renewal. - Myth: Medication alone can cure plucking.

Reality: Drugs may help manage symptoms but won’t resolve the issue without environmental and behavioral changes.

When to See an Avian Veterinarian

Any sudden or severe feather loss warrants professional evaluation. Seek immediate care if you observe:

- Bare patches with inflamed or bleeding skin

- Changes in appetite, droppings, or energy levels

- Discolored feathers or unusual discharge

- Behavioral shifts such as aggression or withdrawal

An avian vet can rule out medical causes and recommend a comprehensive treatment plan. In complex cases, referral to a bird behavior specialist may be advised.

Conclusion: Addressing the Root, Not Just the Symptom

Understanding why do birds pluck their feathers requires looking beyond surface behavior. While occasional feather loss during molting is normal, persistent plucking signals deeper issues—whether medical, dietary, or psychological. By combining proper veterinary care with enriched, species-appropriate living conditions, owners can help their birds maintain both physical and emotional well-being. Early intervention, attentive observation, and a commitment to holistic care are essential in preventing and resolving feather-plucking behaviors.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is feather plucking painful for birds?

Initially, birds may not feel pain, but chronic plucking can damage skin and follicles, leading to discomfort or infection.

Can feather plucking be reversed?

Yes, if the underlying cause is identified and addressed, many birds regrow feathers over time, though severely damaged follicles may not recover.

Do all bird species pluck feathers?

While any bird can exhibit the behavior, it’s most common in highly intelligent, social species like parrots, cockatiels, and lovebirds.

How long does it take for plucked feathers to grow back?

Depending on species and health, it can take several weeks to months. Proper nutrition and reduced stress speed recovery.

Are there medications for feather plucking?

Some vets prescribe anti-anxiety medications or hormone treatments in severe cases, but these are most effective alongside environmental improvements.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4