Birds talk primarily to communicate, establish territory, attract mates, and strengthen social bonds. This vocal behavior, often referred to as bird vocalization or avian communication, is a complex system that varies widely across species. While not all birds 'talk' in the human sense, some—like parrots, mynas, and certain songbirds—can mimic human speech and environmental sounds, a trait driven by both biological adaptation and social learning. Understanding why do birds talk reveals insights into their intelligence, survival strategies, and deep-rooted evolutionary behaviors.

The Science Behind Bird Vocalizations

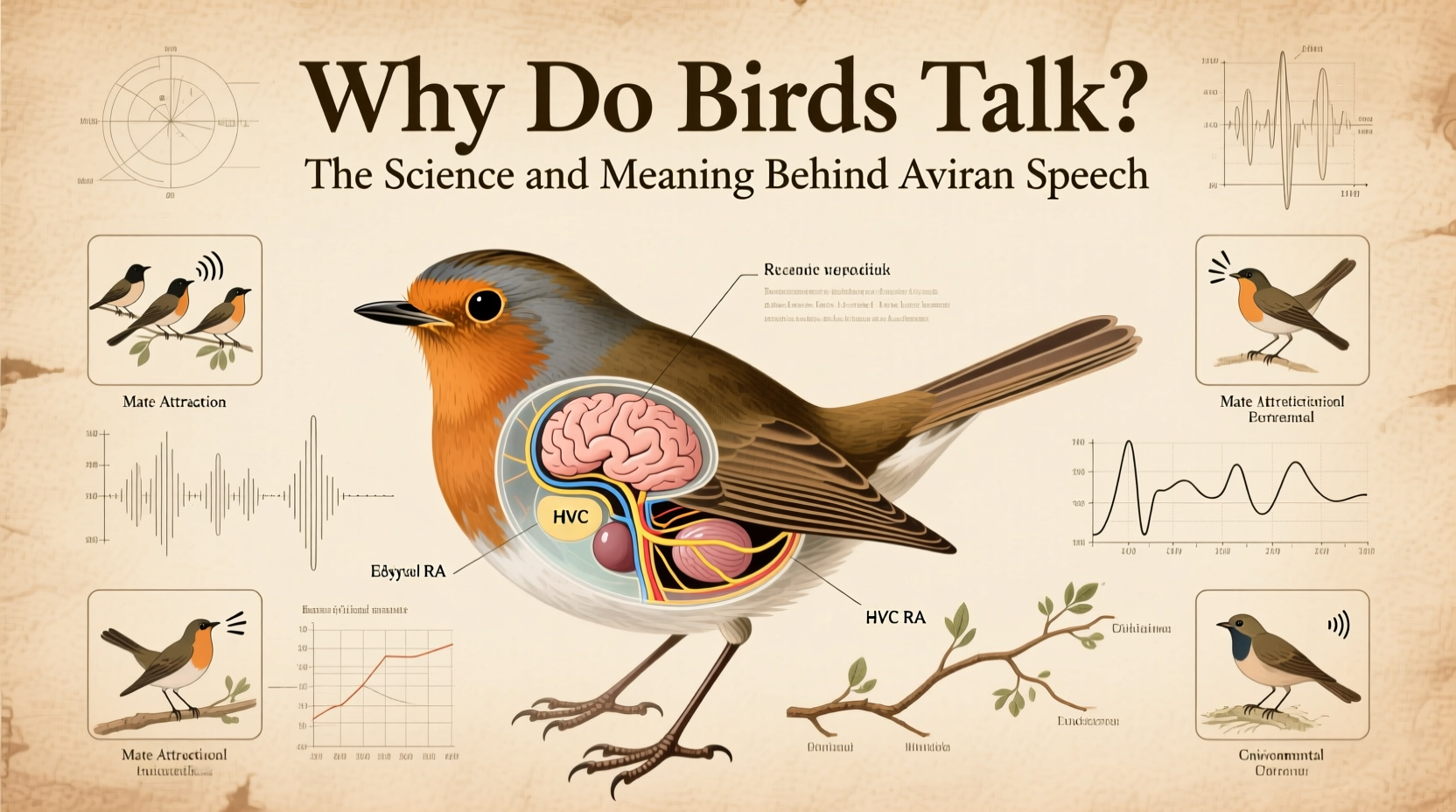

Bird vocalizations are produced using a unique organ called the syrinx, located at the base of the trachea where it splits into the bronchi. Unlike the human larynx, the syrinx allows birds to produce two different sounds simultaneously, contributing to the complexity and richness of bird songs. The ability to generate intricate sounds is especially developed in passerines (perching birds), which make up over half of all bird species.

Vocal learning—the capacity to modify vocal output based on auditory experience—is rare in the animal kingdom. Birds are among the few non-human animals capable of this skill, alongside whales, dolphins, bats, and humans. In birds, this ability is most advanced in three groups: songbirds (oscine Passeriformes), parrots, and hummingbirds. These clades independently evolved similar neural pathways for vocal learning, suggesting strong evolutionary pressure for complex communication.

Neurobiological studies show that bird brains contain specialized regions such as the HVC (used as a proper name in neuroscience) and RA (robust nucleus of the arcopallium), which control song production and learning. Young birds go through a critical period early in life when they listen to and memorize adult songs, much like human infants acquiring language. This process, known as sensorimotor learning, involves babbling-like practice phases before achieving accurate imitation.

Functions of Bird Communication

Birds use vocalizations for several key purposes, each tied to survival and reproduction:

- Territorial Defense: Male songbirds often sing at dawn during breeding season to proclaim ownership of an area. Songs serve as acoustic boundaries, reducing the need for physical confrontations.

- Mate Attraction: Complex songs can signal genetic fitness. Females of many species prefer males with larger song repertoires, viewing them as healthier or more experienced.

- Pair Bonding: Mated pairs of birds, such as gibberbirds or California towhees, engage in duets that reinforce pair cohesion and coordinate nesting activities.

- Alarm Calls: Many species have distinct calls to warn others of predators. Some even differentiate between aerial threats (e.g., hawks) and ground-based ones (e.g., cats).

- Individual Recognition: Colonially nesting birds like penguins use unique calls to locate mates and chicks in crowded environments.

Why Can Some Birds Mimic Human Speech?

Among the most fascinating aspects of avian communication is the ability of certain birds to mimic human speech—a phenomenon commonly observed in pet parrots, hill mynas, and lyrebirds. But why do birds talk like humans? The answer lies in their high cognitive abilities and social nature.

Parrots, for example, are highly social and form tight-knit flocks in the wild. In captivity, they often view their human caregivers as flock members. Mimicking human words helps them integrate socially, gain attention, or receive rewards. Studies show that some parrots, like the famous African grey parrot Alex studied by Dr. Irene Pepperberg, can associate words with meanings, identify objects, colors, and quantities, and even express desires.

Mimicry isn't limited to pets. Wild birds also imitate sounds from their environment. The superb lyrebird of Australia, for instance, can replicate chainsaws, camera shutters, and car alarms. This mimicry likely evolved as part of elaborate courtship displays, where males showcase their neurological fitness through sound complexity.

| Bird Species | Vocal Ability | Natural Habitat | Mimics Human Speech? |

|---|---|---|---|

| African Grey Parrot | Exceptional | West and Central Africa | Yes |

| Amazon Parrot | Very Good | Central & South America | Yes |

| Hill Myna | Excellent | South and Southeast Asia | Yes |

| Song Sparrow | Good (species-specific songs) | North America | No |

| Sydney Lyrebird | Outstanding mimic | Australia | Indirectly (mimics sounds, including speech) |

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings of Talking Birds

Beyond biology, talking birds hold significant cultural symbolism across civilizations. In many indigenous traditions, birds are seen as messengers between worlds. The ability of parrots to 'speak' has led to associations with prophecy, wisdom, and spiritual insight.

In Hindu mythology, the parrot is linked to Kama, the god of love, symbolizing desire and poetic expression. Ancient Greeks believed crows and ravens could deliver divine messages due to their intelligence and vocal flexibility. In modern pop culture, talking birds appear in literature and film as clever companions—from Iago in Disney's Aladdin to Paulie, the lovable parrot searching for his owner.

However, these portrayals sometimes blur reality and fiction, leading to misconceptions about bird intelligence and care requirements. While birds can learn phrases, they don’t understand language the way humans do. Their 'talking' is rooted in pattern recognition and reinforcement, not abstract reasoning.

How to Encourage Healthy Vocalization in Pet Birds

If you own a bird capable of mimicking speech, there are ethical and effective ways to encourage vocal development without causing stress:

- Start Early: Begin training when your bird is young, ideally between 3–6 months old, during its peak learning phase.

- Use Positive Reinforcement: Reward attempts to mimic with treats, praise, or affection. Avoid punishment, which can lead to anxiety and silence.

- Repeat Clearly: Speak slowly and clearly, using simple words or short phrases. Repeat consistently in calm environments.

- Limit Exposure to Negative Sounds: Birds may repeat swear words or loud noises. Monitor what they hear, especially in households with TVs or frequent arguments.

- Provide Social Interaction: Birds thrive on interaction. Spend time daily talking, playing, and bonding with your bird.

- Ensure Proper Environment: A stressed or lonely bird won’t vocalize well. Offer enrichment like toys, perches, and safe spaces.

Remember, not all birds will talk, and that’s normal. Even non-mimicking species communicate through body language, calls, and songs. Respecting natural behaviors is key to responsible bird ownership.

Regional Differences in Bird Vocal Behavior

Birdsong varies regionally, much like human dialects. For example, white-crowned sparrows in San Francisco have distinctly different songs than those in rural Oregon. These dialects emerge when young birds learn local variants from adult tutors. Over generations, isolated populations develop unique song patterns.

Urban environments also influence bird communication. City-dwelling birds like robins and great tits often sing at higher pitches or during nighttime hours to overcome low-frequency traffic noise. Some researchers suggest urban birds are evolving faster learning capabilities to adapt to changing soundscapes.

When observing birds in different regions, keep in mind that vocalizations may differ significantly. Travelers interested in why do birds talk in specific areas should consult regional field guides or join local birdwatching groups to learn native calls and behaviors.

Common Misconceptions About Talking Birds

Several myths persist about why birds talk and what it means:

- Myth: Birds understand every word they say.

Reality: Most birds associate sounds with outcomes but lack full grammatical comprehension. - Myth: Only parrots can talk.

Reality: Mynas, corvids (like magpies), and even some starlings can mimic speech. - Myth: Talking is instinctive.

Reality: It requires learning, exposure, and social motivation. - Myth: Female birds don’t sing or talk.

Reality: In many species, females sing just as complex songs as males, though this was historically underreported.

Observing Bird Communication in the Wild

For birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts, understanding avian vocalizations enhances the outdoor experience. Here are practical tips for interpreting bird talk in natural settings:

- Learn Common Calls: Use apps like Merlin Bird ID or Audubon Bird Guide to match sounds with species.

- Listen at Dawn: Morning is prime singing time, especially in spring and early summer.

- Watch Body Language: Posture, wing flicks, and tail movements often accompany vocalizations.

- Note Repetition and Pattern: Alarm calls are usually sharp and repeated; mating songs are melodic and sustained.

- Use Binoculars and Recordings: Observe from a distance to avoid disturbing birds. Recording apps can help analyze unfamiliar sounds later.

Joining a local Audubon chapter or attending guided bird walks can deepen your knowledge. Citizen science projects like eBird welcome vocalization data, helping scientists track migration, breeding, and population trends.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Why do birds talk to humans?

- Birds mimic human speech primarily for social bonding, especially in captivity. They perceive humans as part of their flock and use vocalizations to interact, seek attention, or earn rewards.

- Can all birds learn to talk?

- No. Only certain species—mainly parrots, songbirds like mynas, and some corvids—have the brain structures necessary for vocal learning and mimicry.

- Do birds understand what they are saying?

- Some birds, like African greys, can associate words with meanings and use them contextually. However, most mimicry is learned behavior without full linguistic comprehension.

- At what age do birds start talking?

- Most talking birds begin mimicking between 3 and 12 months of age, depending on species and individual development. Early exposure to speech increases success.

- Is it cruel to teach birds to talk?

- No, if done humanely. Using positive reinforcement and avoiding overstimulation ensures the process is enriching rather than stressful for the bird.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4